“Koniec świata!” they exclaimed. “The end of the world!”

“Koniec świata!” they exclaimed. “The end of the world!”

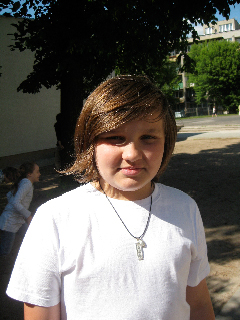

I shifted uneasily with my notebook in hand, scrambling to keep up with Włodek Mikke, Robert Matysiak, Kuba Ziarkowski and Edgar Polański who not only displayed quick wit, but also rapid delivery. Speaking to a visiting journalist may be interesting when you are in the fifth grade, but it is best to do so quickly.

The boys, big football fans, gave a little glimpse of the contradiction facing Polish society in 2009 as it begins its third post-Communist decade with the European Football Championships looming in 2012.

“Everyone will laugh at us because there will be no stadiums,” lamented Mikke. “And our highways suck!”

“It’ll be embarrassing,” echoed Ziarkowski. “It’s probably best to get away, leave the construction and the traffic behind.”

They went on like this for another minute or two, listing every impending calamity and every potential foul-up that will not stand up to foreign ridicule. Eventually, they paused for a moment, looking toward each other self-consciously, perhaps searching for the safety of mutual affirmation.

“Ehh… Leave?” began Polański, breaking into a tentative smile. “Are you stupid? We want to watch the games!”

The boys broke out into laughter, and started talking about their favourite players.

“I don’t know… that’s what everyone talks about,” said Mikke later when I asked him about the doubts. “Media, grown-ups… But that’s stupid, isn’t it?”

Their school, bearing a vaguely romantic plaque declaring to one and all that “Elementary School nr. 75” is named after poet Maria Konopnicka, is nestled in Warsaw’s picturesque Saxon Garden in the city centre. Unlike many other parts of Poland’s capital, it is serene and, on a sunny day in May, rather beautiful.

Their school, bearing a vaguely romantic plaque declaring to one and all that “Elementary School nr. 75” is named after poet Maria Konopnicka, is nestled in Warsaw’s picturesque Saxon Garden in the city centre. Unlike many other parts of Poland’s capital, it is serene and, on a sunny day in May, rather beautiful.

I sat down with the boys, aged 11 and 12 at the time, because I was looking for a particular story. I wanted to connect their present to my own past, and to see how their thoughts and dreams, acquired exclusively in post-Communist Poland, stacked up next to mine, acquired in a similar school just across town before I left Warsaw for Canada in 1991 when I was roughly their age.

We talked about travel, video games, and even a little politics, but I was a little preoccupied because a day earlier, I had come across an essay by economist Krzysztof Rybiński, presently a partner at Ernst & Young Poland and a former deputy governor of the National Bank of Poland.

Rybiński, now 42 years old, is one of Poland’s best and brightest analysts, prone to outbursts of passionate, well-reasoned and polite commentary that makes him an oddity in Poland’s supercharged media sphere.

Rybiński argues that Poland is in line for a period of massive economic expansion between 2011-2020. This “golden decade” will occur because of (1) favourable demographic trends, (2) European Union funds for infrastructure development, (3) advances in e-administration that will eliminate bureaucratic obstacles to starting a business and, (4) an education system that is churning out qualified mathematicians and computer programmers whose talents are comparable to (if not better than) current information technology leaders.

Rybiński argues that Poland may well be in line for the best economic decade in its modern history, and his case is sound. Still, there is one factor that is difficult to quantify, even for the most capable economist.

Here, I return to the boys, who will all enter their prime productive years towards the end of Rybiński’s golden decade, and whose attitudes and worldviews are already being shaped by the world around them.

I have always argued that my generation, those old enough to remember the beautiful earthquake of 1989 but young enough not to have to suffer its aftershocks without the help of parents, is naturally predisposed towards optimism and big dreams. Eastern Europe was objectively poorer and more uncertain so not everyone could realize their aspirations but we all dreamed big dreams for a while-even on the monkey bars.

For the boys today, things are a little different. Epochal change has largely given way to predictable reality, and some of the advances (especially in the realm of consumption) are quite obvious.

“We play football, but we watch a lot of TV too,” explains Ziarkowski, when asked what life is like for young Poles. “Disney Channel, Discovery Channel, cartoons…”

“We love shoot-‘em-up video games!” enthuses Polański. “Online games are the best-we can play with our friends, or beat up on strangers.”

“We love shoot-‘em-up video games!” enthuses Polański. “Online games are the best-we can play with our friends, or beat up on strangers.”

“Travelling,” adds Matysiak. “Not everyone can go, but some people go to Europe, Tunisia, Spain…”

So far so good, but my ears perked up when the boys hit on something that somehow, even 20 years later, remains a major topic of discussion on the playground.

“Politics!” exclaims Mikke. “Boże, co tam sie dzieje! (My God, you should see what they’re doing!)”

With the elections to the European Parliament scheduled for the following week, the boys began to recite each party’s campaign ads. One after the other, they went through an impressive catalogue playfully slinging every accusation, counteraccusation and rumour until one of them turned to the upcoming European Football Championship, scheduled for 2012 in Poland and the Ukraine.

“Koniec świata!” they exclaimed. “The end of the world!”

Euro 2012 will mark the only the second time that the championship will take place outside of Western Europe since the tournament began in 1960, and the looming deadline acts as the perfect motivator for every politician, construction company, small business owner and football fan who hopes to begin Poland’s golden decade on the right note.

The boys too were quite excited, but it says something about the national debate that 11- and 12-year-old football fans were worried about impending national embarrassment not only on the football pitch but in the realm of infrastructure development as well.

This is where we return to Rybiński’s golden decade. Rybiński is right-the moment seems perfect. But, it has to be noted that the economist does not say that Poland must advance, but that it can.

Mikke, Matysiak, Ziarkowski and Polański are bright and their collective aspirations (attending university, studying abroad, starting a business) are admirable and can contribute immensely to Poland’s continued development. But what stands in their way is the collective “Koniec świata!” something that they did not learn to say on the playground, but brought along with them from the world around them.

Whether Poles collectively seize the opportunity has a lot to do with the character and ambition of the population, including that of today’s kids. If Poland, their Poland, is to seize its economic moment in the sun, such attitudes need to shift.

CR

Imagery

- Włodek Mikke

- Elementary School nr. 75 nestled in Warsaw’s picturesque Saxon Garden close to the city centre and Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

- Kuba Ziarkowski

Photos by Kris Kotarski