There can be no doubt that Wisława Szymborska will enjoy a lasting place in the attention of American readers. That is, for as long as “lasting” can be for any of us. Such a caveat is essential in any discussion of what Szymborska does, for she is, first among the many things she could be, a poet of scale. From celebrated early poems like “Nothing Twice” and “Notes from a Nonexistent Himalayan Expedition,” which pleads with a “Yeti” high up in the mountains to consider what the world looks like to a human eye; to poems from her middle period like “Census,” “Snapshot of a Crowd,” “A Large Number,” “Seen from Above,” and “View with a Grain of Sand”; to “Cat in an Empty Apartment,” her quietly wrenching elegy for the writer Kornel Filipowicz, her longtime partner, which muses over how his cat might respond to his sudden absence—throughout her career Szymborska returns to the question of how our reality appears without us, whether from a scale far above (the Yeti’s, the census-taker’s) or far below (the cat’s, the grain of sand’s).

There can be no doubt that Wisława Szymborska will enjoy a lasting place in the attention of American readers. That is, for as long as “lasting” can be for any of us. Such a caveat is essential in any discussion of what Szymborska does, for she is, first among the many things she could be, a poet of scale. From celebrated early poems like “Nothing Twice” and “Notes from a Nonexistent Himalayan Expedition,” which pleads with a “Yeti” high up in the mountains to consider what the world looks like to a human eye; to poems from her middle period like “Census,” “Snapshot of a Crowd,” “A Large Number,” “Seen from Above,” and “View with a Grain of Sand”; to “Cat in an Empty Apartment,” her quietly wrenching elegy for the writer Kornel Filipowicz, her longtime partner, which muses over how his cat might respond to his sudden absence—throughout her career Szymborska returns to the question of how our reality appears without us, whether from a scale far above (the Yeti’s, the census-taker’s) or far below (the cat’s, the grain of sand’s).

In this respect, there may be no more effective visual précis of Szymborska’s lyric output than Powers of Ten, the documentary short produced in 1968 by Charles and Ray Eames to demonstrate how orders of magnitude shift our perception of place.

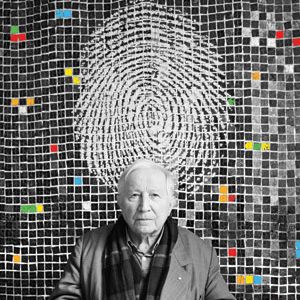

As the narrator reiterates throughout the film, what we think of as “reality” may mean different things depending on the breadth or focus of our gaze. Especially when that gaze is not “ours” but, say, that of Szymborska’s “Clouds”: “Let people exist if they want, / and then die, one after another: / clouds simply don’t care / what they’re up to / down there.” While it is not always productive to speak of a poet’s career in terms of an overarching project, this attention to scale is a central feature—arguably, the central feature—of Szymborska’s oeuvre. Even her whimsical collages, typically consisting of just two or three elements cut out from magazines, often place a familiar image in a new background, either vastly broader or more constricted than what we, the viewers, recognize as the figure’s proper place. Take, for example, what she does with Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, notorious in art history for the multiple lines of sight generated by those crowding around the Infanta Margarita.

Szymborska plucks Margarita from this bustle and, presumably, from all the onerous social obligations incumbent on an heir to the Spanish throne, and instead inserts her into a pastoral paradise. The Infanta’s new setting is incongruous not only in how it would likely blemish her silken finery, but because of scale: she is suddenly taller than the trees and likely to trample the Lilliputian sheep grazing nearby.

The image’s effect is ironic, and Szymborska is, of course, an exceptional ironist. This, too, is a consequence of her attention to scale. In a great many of her poems, we see the world from the poet’s own point of view and, simultaneously, from the perspective she self-consciously imagines as belonging to an utterly indifferent universe. No wonder, then, that in her 1996 Nobel lecture Szymborska declared Ecclesiastes, “the author of that moving lament on the vanity of all human endeavors,” to be “one of the greatest poets, for me at least.” Note the caveat. Far be it from Szymborska to make what sounds at first like a universal claim; she must immediately ground it in her own individual perspective. Rather than foster a dim, even nihilistic view of human activity, however, this sober regard makes room for what she calls “astonishment,” the sudden, quintessentially human realization that there is nothing ordinary about the world or our place in it. Michał Rusinek, her longtime secretary, has recently suggested a similar relation between the specific and the general in Szymborska’s work. “She was near-sighted,” he says in an interview for Tygodnik Powszechny, “also in the sense that what interested her was the detail, and she discerned interconnections among things that normally go unnoticed. She was not a creature of erudition, but someone who knows how to draw amazing, general conclusions from looking at details.”

And since irony ranks among the most consistently grueling, if attractive, challenges for the translator, Szymborska’s poems have enjoyed exceptional reworking by several. These have included selections by Magnus J. Krynski and Robert A. Maguire in the early 1980s and, more recently, Joanna Trzeciak. Stanisław Barańczak and Clare Cavanagh, meanwhile, have made almost the entirety of Szymborska’s poems and prose available to the Anglophone reader. It’s worth noting, if only as a token of her worth to us, that few postwar writers not writing in English have been welcomed so thoroughly into English. But I expect that there will be still more versions. Szymborska’s poems are a prime specimen of what Walter Benjamin calls “translatability,” the quality of certain texts to unfold into variations of themselves. The poet of scale offers a theme—that of our own situatedness—that is relatable to all of us who have thought seriously about our humanity, and that still encompasses those of us who have not. This she makes clear in the poem from which she derives the title of That’s Enough, her last, posthumous collection of poems. In “Hand,” over a mere seven lines, she notes her subject’s modesty, “twenty-seven bones, / thirty-five muscles,” and yet this is “quite enough / to write Mein Kampf / or The House at Pooh Corner.”

And since irony ranks among the most consistently grueling, if attractive, challenges for the translator, Szymborska’s poems have enjoyed exceptional reworking by several. These have included selections by Magnus J. Krynski and Robert A. Maguire in the early 1980s and, more recently, Joanna Trzeciak. Stanisław Barańczak and Clare Cavanagh, meanwhile, have made almost the entirety of Szymborska’s poems and prose available to the Anglophone reader. It’s worth noting, if only as a token of her worth to us, that few postwar writers not writing in English have been welcomed so thoroughly into English. But I expect that there will be still more versions. Szymborska’s poems are a prime specimen of what Walter Benjamin calls “translatability,” the quality of certain texts to unfold into variations of themselves. The poet of scale offers a theme—that of our own situatedness—that is relatable to all of us who have thought seriously about our humanity, and that still encompasses those of us who have not. This she makes clear in the poem from which she derives the title of That’s Enough, her last, posthumous collection of poems. In “Hand,” over a mere seven lines, she notes her subject’s modesty, “twenty-seven bones, / thirty-five muscles,” and yet this is “quite enough / to write Mein Kampf / or The House at Pooh Corner.”

For as long as “lasting” can mean for anyone, Szymborska will have a lasting place in our literature—whatever “our” means—because she reminds us time and again that we cannot appreciate what it means to be here without imaging what this “here” might be without us. “Just take a closer look,” she urges us in the title poem of her collection Here,

the table stands exactly where it stood,

the piece of paper still lies where it was spread, through the open window comes a breath of air,

the walls reveal no terrifying cracks

through which nowhere might extinguish you.

CR