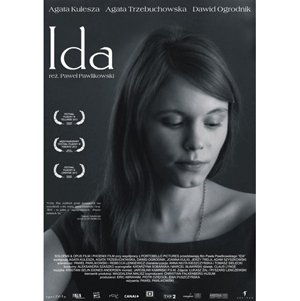

Róża

Róża

Polish with English subtitles

Directed by Wojciech Smarzowski

2011

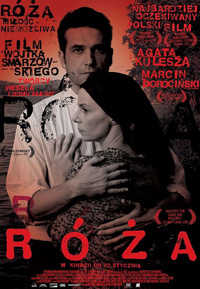

When Wojciech Smarzowski’s 2011 critically acclaimed film Róża was screened at the annual Ann Arbor Polish Film Festival, I couldn’t wait to see it. The drama, set in the chaotic aftermath of World War II, had amassed many prestigious awards. At the 2012 Polish Film Awards, it practically did a sweep, racking up “Orły” for Best Picture, Director, Performance by a Lead Actress, Performance by a Supporting Actor, Sound, Screenplay AND the Audience Choice Award. I expected to be blown away.

And I was. Róża’s cinematography and acting are simply stunning, though “harrowing” is probably the adjective that best describes my viewing experience. The film chronicles the experiences of former inhabitants of East Prussia at the end of World War II who suddenly find themselves living in a newly constituted Poland. Known as the Masurians, they were considered German by the new regime and therefore became victims of discrimination, theft, starvation, and ultimately deportation.

Róża, the eponymous heroine, is a bilingual Masurian who is at the mercy of the Soviet occupiers, the collaborationist government, and her own ethnic community. Rejected by all, she struggles to protect her daughter from the sexual violence she herself is subject to throughout the film. The movie is punctuated continually by rape scenes, a grim reminder that wars are fought not only on the battlefield, but also on and through women’s bodies.

Tadeusz, the male character around whom the film actually revolves, tries to shield Róża and her daughter from this violence. A laconic but handsome ex-Home Army soldier who has returned from fighting in the Warsaw Uprising, Tadeusz decides to settle on Róża’s homestead (with her permission). As we find out in the first scene, Tadeusz is also deeply affected by the rampant sexual violence depicted throughout the film – his wife was brutally raped and murdered while he lay helplessly in the rubble, his bloody face contorting in rage. Róża, in a certain sense, becomes the wife he couldn’t protect.

Agata Kulesza’s performance as Róża is nothing short of masterful. There isn’t much dialogue in the film; the indescribable horrors of the war have robbed the heroes of their need to speak. Instead, the most powerful scenes are those in which the actors communicate silently, bodily. In the beginning of the film, Kulesza’s hard, angular face expresses a weariness and mistrust that comes from the innumerable hardships she’s endured. However, these physical and emotional calluses soften under the devotion of Tadeusz, although they never quite disappear. Rare moments of happiness, even gaiety, grant the viewer a respite from a harsh and dangerous reality, yet it is a reality to which the film inevitably returns, again and again.

Despite the film’s title, Róża‘s action begins and ends with Tadeusz, played by Marcin Dorociński. In many ways he embodies the classic Polish hero, fights for his ideals and home, and in the process suffers intensely. What marks Tadeusz as so very Polish, however, is that he is, and remains throughout the film, relatively helpless against the sheer strength of the occupiers/collaborators. From the uprisings of the 19th c. to martial law, the Polish hero’s history is one of apparent failure. Despite Tadeusz’s best efforts, Róża is raped repeatedly when he leaves for town; even when he is able to thwart the Soviet soldiers’ attempts at rape and perhaps murder, he still cannot save her from the damage of past violence. However, he maintains his integrity even under torture, which parallels the Polish national narrative – Poland may be besieged, sacked, and occupied but, underneath, a national spirit still perseveres. Indeed, the ending indicates that despite everything that has happened, a future, albeit uncertain, awaits the family.

This national narrative, however moving, also has its biases. In his review of Róża in Gazeta Wyborcza, Tadeusz Sobolewski writes of the film: “evil has no uniform nor nationality, it lurks everywhere.” I disagree with this assertion. In Smarzowski’s film, evil wears a Soviet uniform. The utter bestial cruelty of the Soviet occupiers is unambiguous and in the foreground, while the more interesting, in-depth characterizations are exclusively Polish or Masurian. Every Soviet soldier is drunk, stupid, mentally unstable, or a rapist. Or all of the above. This is not to say I am on the Soviets’ side of history; indeed, I understand the atrocities that were perpetrated by Soviet troops, and Róża is ultimately a story about the widespread raping of women as common practice in war culture. Yet, let me suggest two things: Soviet troops were also human beings, and many were traumatized by the war, and that other armies, including the Home Army, were not completely innocent of these crimes. If anything, recent literary and cinematic treatments of World War II have shown that in extraordinary circumstances, humans are capable of great moral conviction as well as unspeakable acts in the name of survival or under the influence of ideology. Illuminating the humanity of the Soviet troops, fleshing out their characters just a bit, would have been a more powerful statement about the nature of war or occupation and their moral and psychological effects. I think a film that could soften the stereotypes of Russians as uniformly barbaric and inhumane would be more thought provoking, to say the least.

Regardless of my criticisms of the characterizations, the movie is incredibly rewarding if you can sit through the violence. The graininess of Piotr Sobocinski’s lens both foregrounds the dirt and grit of a farm in rural Poland, and enhances the natural beauty of the countryside. Greens, browns, pale yellows, and dirty whites predominate, which give the film an almost banal, quotidian quality, were it not for the intensity of the violence that weaves throughout the narrative. The summer scenes are palpably hot, while the winter bone-chilling cold. Despite the dirt, drab colors, and grim content, Róża is one of the prettiest films I’ve seen in some time.

If you are in the mood for an arresting film that will leave you tear-stained, I recommend Róża. By no means saccharine or melodramatic, it is instead a stark, harsh depiction of a government attempting to take hold of a country with newly-drawn borders, a transition that relies on the “resettlement” of millions. With the Masurians as its case study, the film hammers home the chaos that follows any war, and argues that conflict doesn’t end with the signing of a treaty. CR