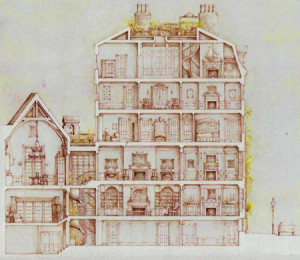

Louisburg Square Building Section; one of Monika Pauli’s projects in Boston’s Beacon Hill

In the “liquid times” in which we live, to borrow the term coined by Zygmunt Bauman, where stories and news appear in rapid-fire succession, where bulldozers clear the way for new shopping centres and highways, and where yesterday is quickly forgotten, the need to preserve cultural heritage and salvage dilapidated buildings once full of life—not only because of their historical value but also because of their sustainability—is more urgent than ever.

Monika Zofia Pauli

Monika Zofia Pauli, a Polish-born architect who co-founded Pauli & Uribe Architects, LLC, located in the historic neighbourhood of Beacon Hill in Boston, believes that “historical preservation should not be viewed simply as nostalgia, but as part of a goal of achieving sustainable life style as opposed to the philosophy of extraction and depletion based on the original American frontier mentality. Extraction and depletion and violent loss of the past can happen abruptly, such as during the War in Poland, or simply by the demand to produce things cheaply and quickly.”

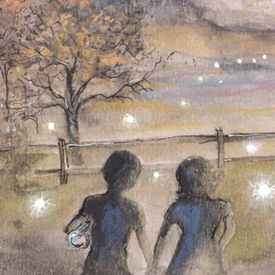

Monika’s illustration from a children’s book emphasizing nature conservation

Pauli’s interest in historical preservation arose from the stories she had heard throughout her adolescence from her parents who escaped communist Poland along with her in the 1970s and came to the US via the former Yugoslavia and Austria as political refugees. Pauli’s mother, an artist educated at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts, and her father, an engineer with a degree from Warsaw Polytechnic, decided to leave Warsaw, disenchanted by the reality of the post-war political landscape in their native country. They survived World War II and the Warsaw Uprising, a barbarian destruction of the capital of Poland by the Nazis, only to find themselves in a country ruled by a communist government dependent on the Soviet Union. With their idealistic outlook and artistic sensibilities, they lamented not only the senseless loss of human lives during the war but also the loss of the cosmopolitan culture of pre-war Poland. During the war they witnessed the Nazis’ systematic destruction of the majority of Warsaw, the bombardment of the Royal Castle dating from the fourteenth century, and the complete destruction of the Old Town many of whose houses were built in the fifteenth century. After the war, Mr. and Mrs. Pauli saw not only the reconstruction of the city but also the new architecture of social realism imposed by the Soviet Union. They also saw the demolition of some of the surviving historical houses that were unwelcome in the present urban landscape because they represented bourgeois values.

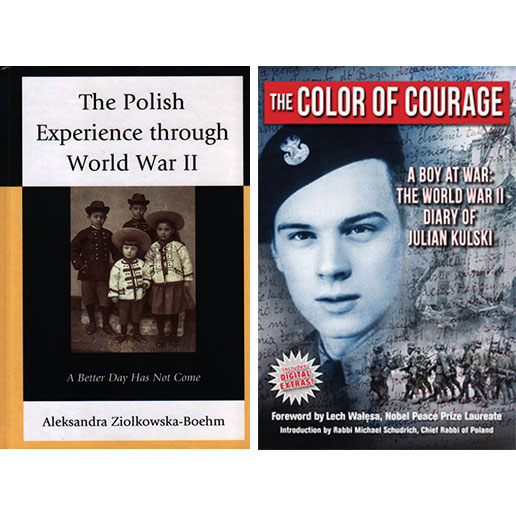

Children’s book, illustrated by Monika Zofia Pauli

In America, Pauli’s parents told her not only about the barbaric events of the war but also about interwar Warsaw, then known as the “Paris of the North.” Despite daily struggles common to new immigrants, art and history continued to form the fabric of their lives. Monika Zofia Pauli saw how precarious the life of an artist could be while watching her mother, and even though she loved painting she pursued a career in architecture. As an architect, she believes, one can shape the whole environment, which is why the architect’s responsibility is greater than that of the artist. She graduated from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and completed her master’s thesis on “Energy Conscious Design: Socio/Economic Historical Study and a Master Plan for Troy New York and R.P.I.” It is not only wars, Pauli argues, but also reckless human actions— sometimes even well-intentioned ones (such as urban renewal and highway construction projects in the US) that are not always profit motivated—that can destroy a valuable historical environment. Progress, although beneficial, has to be carefully considered. Preservation is actually more progressive and ecologically responsible than reckless demolition and poorly conceived growth. She quotes the words of a fellow architect, Carl Elefante, who remarked that “the greenest building is one that is already built.” In her over twenty-five-year practice Monika Zofia Pauli has concentrated on historical preservation, alterations to existing buildings and new construction sensitive to historical settings in urban historic districts. She draws using traditional, historically based, hand-rendering techniques. During the last four years she has been serving on the Cambridge Historical Commission reviewing all new construction in Cambridge, MA, encouraging preservation while enhancing economic vitality, and guarding the city’s evolution while encouraging new construction.

The Château; exterior view

In addition to the restoration of several houses in Massachusetts, she contributed to the restoration of a ruined seventeenth-century château in France that her parents bought in 1997. Poet Zbigniew Herbert reminds us that:

“all we have left is the place the attachment to the place

we still rule over the ruins of temples spectres of gardens and houses

if we lose the ruins nothing will be left”

Restoration in progress at the château in France

The desire to preserve the ruins and to regain the lost past drove her parents to buy and restore the château, which everyone else thought was beyond salvageable. The château (in Gascony, a south-western region of France) was originally completed in 1371 and then rebuilt three centuries later. It had no electricity and no heating system, and in the evenings bats flew around the château tower. Pauli steadfastly believed in her parents’ dream, and thus she helped them transform the ruin into a living space. She wanted to preserve the original character of the place, and her extensive experience as an architect involved in historical conservation came in handy. The original plaster was restored as well as the cobble stones on the ground floor that likely date from the fourteenth century.

Monika Zofia Pauli worked with her parents as a team on restoration in France; view shows mother’s wall paintings

When Pauli’s father was digging under the floor to install the electricity, he discovered a pair of leather shoes, seventeenth-century galoshes that the ladies wore over their silk shoes in order to protect them from the rain and mud. They were put there when the floor was renovated and were said to bring good luck. Today the château is meticulously restored and fully liveable.

Château interior

Looking at this historic structure, which is a national landmark, Monika Zofia Pauli sees that many centuries ago its architect designed it as what we would today call a passive solar home to minimize energy—with south-facing windows, one-metre-thick stone walls that keep warmth in winter and cool in summer, and deeply embedded foundations. The château in its current state will endure many hundreds of years. For Pauli’s parents, who witnessed the bombardment of so many monuments, it is something of a miracle that, with their daughter’s assistance, they were able to resurrect the past, to salvage the ruins. “There is a need to link past, present and future and prevent degradation of the environment,” says Monika Zofia Pauli. “I suppose I feel so strongly about it coming from a country which has been ravaged by war.”

CR