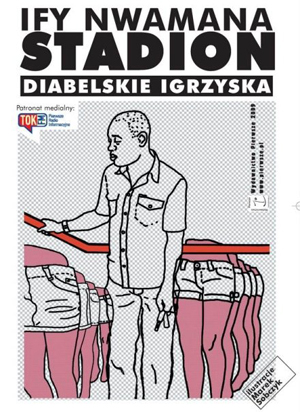

Stadion. Diabelskie Igrzyska.

Stadion. Diabelskie Igrzyska.

By Ify Nwamana

384 pages, 2009

Wydawnictwo Pierwsze

ISBN: 978-83-927952-2-3

Paul Beatty’s Slumberland begins with a black man from Los Angeles finding solace in a Berlin tanning salon. The winter is all encompassing – in Beatty’s words, an “epoch” – and the tanning lamps in the windowless “Acapulco” room give Ferguson W. Sowell a moment to contemplate his place in the world.

“You would think they’d be used to me by now. I mean, don’t they know that after fourteen hundred years the charade of blackness is over? That we blacks, the once eternally hip, the people who were as right now as Greenwich Mean Time, are, as of today, as yesterday as stone tools, the velocipede, and the paper straw all rolled into one? The Negro is now officially human. Everyone, even the British, says so. It doesn’t matter whether anyone truly believes it; we are as mediocre and mundane as the rest of the species.”

Beatty’s opening paragraph – and especially those last three lines – immediately sprung to mind after I put down Ify Nwamana’s Stadion: Diabelskie Igrzyska (Stadium: The Devil’s Playground), the first and only book that I have ever come across written by a black author specifically for the Polish audience. Although the American Beatty and the Nigerian Nwamana share little more then their humanity and their dark complexion, Nwamana’s work is supreme proof that Beatty’s instincts were right, and that “blackness” need not be extraordinary anymore, even if not everyone truly believes it.

Beatty’s own book may have offered this insight (along with many others), but his engaging prose obscured it, the incredible characters and exotic situations overwhelming the reader bit by bit. Nwamana, on the other hand, constructed something different, most likely with far more difficulty since stylistically he is not a writer of Beatty’s talent. His novel about the African immigrant experience in and around the sprawling marketplace in Warsaw’s dilapidated Stadion Dziesięciolecia – 10th Anniversary Stadium – was every bit as sincere in its attempt to discern the meaning of blackness, even if it challenged the reader in a far more modest manner. Where Beatty hit high note after high note with his urbane prose focusing on Sowell’s philosophy and culture and his perceptions of light and sound, Nwamana focused on the inner workings of the immigration system and the African dream of making money in Europe, with his protagonist, Mike, far more reminiscent of the black security guard who, in Beatty’s book, observed that “Germany is the black man’s heaven . . . You just have to let them love you.”

In Stadion, Poland loves Mike and, rather stereotypically, marvels at his virility. Polish customers love Mike because of his counterfeit merchandise and Polish women love Mike because of his aggressive masculinity. Money and bodily fluids flow freely throughout the narrative, yet, for all the love – described most often in boasting detail – the book begins with violence, opening with a police sweep of the sprawling stadium by a paramilitary unit charged with disrupting the sale of counterfeit shoes, shirts and CDs. The “masks,” as Nwamana calls them, and the fear and panic that accompany them, are the first great unifier with both peddlers and customers affected by the sudden encounter with the bristling state. Yet, although such unity says something about first reactions, it is only momentary, and as the book clumsily veers from the stadium to family life and adulterous intrigue, Mike’s relationship with his new society grows ever more ambiguous and complex.

Nwamana based his main character on his own experiences as a shoe dealer at the sprawling and now-defunct Warsaw market, and his own recollections of raids, customers and behind-the-scenes machinations give incredible colour to his description of life in Warsaw. Nwamana, a debut author, is at his best when he describes the stadium with its arcane rules and corrupt structures, and although he sometimes sounds conflicted, he manages to pass judgement through the eyes of his protagonist and the friends, lovers and customers who engage him in everyday encounters.

If this were Canada or the United Kingdom where the narratives around immigration and expatriate “blackness” are far more developed, Stadion would be a fascinating collection of colourful stories about the immigrant underworld, a common, if interesting, part of the greater narrative. Because this is Poland, where “blackness” should not yet be “mediocre and mundane,” Nwamana’s book is an interesting statement about the morals and values of the immigrants and the post-Communist society trying to absorb them.

For this reason alone, Nwamana could have succumbed to the temptation to whitewash the misdeeds of the Africans, and presented his characters in a heroic light, if for no other reason then his own pioneering role in black Polish literature. Yet despite the sharp and often critical passages about the treatment of Africans in Poland and about the misadventures of Mike and his colleagues when dealing with officials and bureaucrats, Nwamana’s Africans are among the darkest characters in Stadion, with the narrative skipping from lies, to infidelity, to theft, and back again.

This is an interesting book, with a number of sympathetic characters who become less and less sympathetic as the narrative progresses, and with political undertones that start out clear but become muddled with time. Part of this may be due to Nwamana’s inexperience as a writer, but I still couldn’t help but think of Beatty’s lines.

“The Negro is now officially human. Everyone, even the British, says so.”

CR

Krzysztof dedicates this article to John Thesiger, who has a knack to get a good conversation started.