Piotr Uzarowicz’s grandfather was one of the nearly 22,000 Polish prisoners of war executed in the Katyn massacre of 1940.

Piotr Uzarowicz’s grandfather was one of the nearly 22,000 Polish prisoners of war executed in the Katyn massacre of 1940.

Piotr recently completed The Officer’s Wife, a documentary about Katyń and the far-reaching effects the massacre – and its cover-up – had on the Uzarowicz family.

The film is an ode not just to Piotr’s grandfather: Piotr’s grandmother and father, deported to Siberia during the war, are also key players – as is Piotr himself, who journeys to Poland, Russia, England, Canada, Ukraine and the U.S. on his film-making and personal odyssey.

The Officer’s Wife previewed in May at the Kosciuszko Foundation in New York. Justine Jablonska attended and spoke with Piotr about his film.

* * *

Do you have the sense that our generation is bringing this conversation into mainstream consciousness in a way that previous generations were unable to do?

It doesn’t seem to me that it’s part of the Polish identity to push out these kinds of stories about our culture outside of our own communities. We keep them very close to ourselves. Which has been a mistake, because Poland and Polish culture have been very misunderstood for a very long time.

We haven’t done anything to fix that or to change it. I don’t know why it’s taken so long for Polish youth to stand up and start saying something in a broader community. It clearly is very important; we need to do that.

All of us know what happened. That’s not what we’re talking about here – we’re talking about the rest of the world that doesn’t know, that wants to know.

I’ve done several test screenings in Los Angeles, with Americans who know nothing [about Katyń]. They come in and their jaw is on the floor: “Why haven’t I heard about this before?” “Why has this not been in history books?” They’re phenomenally interested in what this is.

There’s been a missed opportunity here for many, many years. A void that we can fill and that we should be filling. We should be throwing as much information into it as possible.

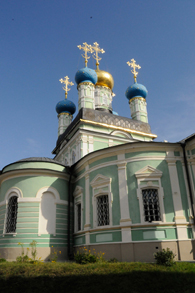

St. Nilov Monastery, Ostashkov, Russia

The Polish POWs were held in 3 prison camps before they were executed:

Kozelsk, Ostashkov, Miednoye.

People don’t care about things they’re not invested in or don’t know about. If they don’t know about it, how can they care about it? But they’re not going to know about it unless we tell them about it.

That was something I had a lot of conversations about in terms of figuring out how to tell the story of this film. How does it become broad enough to interest larger audience. What do you talk about to pull them in? How do you make it relevant? How do you make people care?

We settled on a mixture of things. Some people grab onto the family; some grab onto the tragic human loss; some people grab onto the conspiracy.

There are several elements that give a wider swathe for people to latch onto, in the hopes that we can reach that wider audience, and give them something to think about and care about.

Could you introduce your film to those people who haven’t yet seen it?

The topic itself has always been something that I’ve been interested in. Many years ago I thought this would make a great feature, like a narrative film. At the time I didn’t know [Andrzej] Wajda was working on one. As soon as I discovered that, I stopped moving in that direction.

I realized as I was starting all my research that there’s never been a good documentary on the topic – I mean that from the American side. I’m certain that there have been quality documentaries made in Poland for Polish people about the topic over the last 20 years. The few that have made it to the United States were all really slanted with highly propagandistic view of the events and ultimately didn’t do a good job of explaining what [Katyń] was.

When you say slanted, what do you mean?

Very anti-Russia. Lots of finger-pointing – and no explanation. There wasn’t any human side to this story. It was just: this event happened and these people were killed and these people were responsible. And that was it.

I value and admire that these people made these movies, but what really stimulated me was that there wasn’t one made for the American market. And I felt that I could do one.

I started doing something very much different than what is the final product. My grandfather was one of the officers’ murdered there, and I figured I would tell the story about Katyń focusing on my grandfather as a way into the story.

It went along that way for a little bit. I was doing research, starting interviews, talking to many people – and then my dad died. It was a bit sudden.

As I open the film, I talk about how when a parent dies, there’s a lot of stuff that needs to happen.

I had to go to the bank and check the safe deposit box. And it was there that I discovered this tin, and in the tin there was a manuscript my grandmother wrote. There was a postcard, several photos of an officer. It was the first time I’d ever seen any of these things. It immediately became clear to me that that was the way to tell the story. That it’s not a piece of history long-gone; it’s a family tragedy. And that it continues today – because these people are still around. That was the story that’s never been told.

What did the postcard say?

Part of it is certainly personal, but in general he wrote that he was being held in Ostaszkow [one of the camps where Polish prisoners of war were kept and later executed], and that Cecylia [his wife, Uzarowicz’s grandmother] should be cautious.

You could tell he was concerned and that was the letter that they preserved.

Was that the only postcard they received?

I know they received two.

That’s pretty common, right?

It does seem that two is the number – however, no one’s ever been able to show me two. Even within my own family there’s only the one. Even though Cecylia wrote in her memoirs that she received two, I only have one. For whatever reason, the second one didn’t make it through.

Miednoye, Russia

The Polish victims were buried in 3 mass gravesites:

Katyń, Miednoye, Kharkov

You include footage from what you call a “creepy Nazi film.” What is that film?

Piotr: It’s titled “Im Walde von Katyn.” The Nazis made the film when they discovered the bodies in 1943. It’s probably the most well-known film that was made about Katyń. It made it into every possible Nazi newsreel at the time. It was widely broadcast.

Once the Soviets took back the Katyń forest, they made their own film. There’s a Russian version of that film as well. Wajda uses it in his movie. I didn’t feel it was necessary in mine. In that film, it’s basically the Soviet retort to the Nazi finger-pointing: The Soviets didn’t do this, the Nazis did.

There’s a part in that film where a body is lifted and then propped up into a sitting position. It’s pretty gruesome. Why was it was important to show that?

Both the Nazi and the Soviet films have some very grotesque scenes in them. What’s in my movie is certainly not the worst of it. The intent of it – certainly part of it is shock value. In today’s world you almost need that to drive the point home, how brutal that was.

We’ve all seen photos of the Katyń bodies, and they’re always lying down. But there’s something about the body being propped up – it makes it more human.

There’s a big difference between photo and video. Seeing something get moved is more powerful than a photo.

In the film, after you discover the postcard you say there’s all these questions you wanted to asked your father. Would he have answered your questions? You said you’d never had that conversation.

What these people went through was a massive trauma. I believe that they’re all suffering from some form of PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]. I think that becomes very clear in the movie. Each one – survivors and descendants – has a unique way of discussing the issue. You can tell that they’re suffering and this is their way of dealing with the issue.

Whether or not my dad would ever talk about it with me, I don’t know. Maybe now – after he’d seen what I’d done with the topic. It’s hard for me to say. I certainly think that he would. But I’m sure there’s a reason why he never talked about it before.

Whether or not I could’ve asked him those questions – I couldn’t, because I didn’t know what to ask. And what to ask only came out after he passed away.

You open the film with moments of levity – your Dad is goofing around a bit in home videos. Why those moments?

Particularly in the beginning of the film, it’s where everyone can relate to someone in their family: He’s a real person. He’s not cowering in a corner, holding his head down, shaking, “How did this happen to me?”

Though in the film, later on – particularly after my grandmother passed away – there’s certainly moments where he’s staring off into space and you could tell there’s something going on. Those were good moments to illustrate that there was more to him than just what we saw externally.

That was key also for me to do with Mieczyslaw, my grandfather, whom I did not know at all aside from the photographs. Reading my grandmother’s memoirs exposed him to me, and the other half was finding his military record: A tome of information about who he was, and what he did.

He was not only very successful at being an officer in the army – he was awarded many times – but also had his points of levity – getting drunk, getting thrown in the brig – it showed that he was also human. He wasn’t this superman who all he did was fight Nazis and Soviets. He was a normal guy that you’d love to know.

Miednoye, Russia

That’s one of the reasons I think the film works. Katyń is, for Poles, a hallowed, sacred thing. The human aspect becomes –

– it becomes lost.

That’s been very difficult to explain to people. People didn’t like that it is from the perspective of someone who survived, who descended from this. These people were martyred and therefore they’re not human anymore, which is a mistake.

If you show their humanity – it doesn’t take away from the martyrology or the crime. To me it becomes even more of a tragedy. Your grandfather was just one of tens of thousands and they all had quirks, personalities, families. But for some reason we haven’t been able to speak about Katyn that way yet.

I certainly hope that this is helping open the door a little bit. It’s very surprising that it’s taken this long for something like this to happen. I was very surprised when I started doing the research that there wasn’t more on the topic. There’s lots of Polish filmmakers; lots of Polish-Americans who are in the business that could have done something.

I wonder why that that is? One of the historians I interviewed [for an article about Katyń] said that it’s a complex story. It takes a lot of explaining for people to understand it and thus be able to engage it. But that’s not an excuse – just because something is complicated; so what? Let’s explain it.

Hopefully I explained it well enough to be able to do that.

You use drawings in the film – how did those come to be?

I’m particularly fond of those. I had to find a way to bring us into Cecylia’s story. The immediate conclusion would be, let’s re-enact it. I don’t like re-enactments; I find them fake. I didn’t want to see my grandmother, grandfather played by somebody.

The next logical step was, let’s create them in a different way. CGI [computer-generated imagery ] wasn’t the answer because it’s too detailed. I needed a step removed from that. It took a long time to find the right style of illustration. I was very fortunate to find the illustrator I did, Dave Spafford, who’s great.

The idea was not just to have this pencil and paper look to it – but also, could it have been drawn by Cecylia in the 40s and 50s about what she went through? It has this old-y feel to it too that gives it a certain intangible reality.

Piotr Uzarowicz in Warsaw, Poland

You titled your film “The Officer’s Wife,” but it’s also very much your journey. You’re an integral part of the story. How did that happen?

Piotr: Bringing myself into it made a lot of sense because the story became about family, and understanding my family. And the only way I could do that is if I became part of the film.

How was that for you?

Piotr: It’s a little awkward. You don’t want to come off as pompous but at the same time you have to figure out how to make it make sense. But that was the idea – it’s a family story so you need to show the family.

One character in the film says, “We didn’t wash for days. It was horrendous.” And then she giggles. That was telling. She’s not laughing about it – but it’s a giggle, and it points to what you said about people processing this and communicating it differently.

Sophie is a very interesting character – I love all of them. For them to open up and share what they did was really brave on their part. That’s also what was interesting about the process, to discover how each of them had been dealing with it their whole lives. Each does very obviously deal with these issues differently – and you could see that in the way they talk about it, the way they react, in the way they look at the camera, the way they don’t look at the camera, what they’re doing with their hands – all those pieces give you a picture of what their lives have been like because of this.

There’s a moment where one of the gentlemen breaks down.

It is a story about parents and fathers. They may be in their 70s or 80s, but it’s still their dad or uncle. I felt that it was good to show that these people still think about their families.

A lawyer near the end of the film says that Russia is the legal successor to the Soviet Union and can be charged for its crime. [Historian] Norman Davies confirms that.

That is how these families have a measure of recourse: Russia’s made itself the legal successor to the U.S.S.R. So therefore it is responsible for those actions.

You can begin to understand why they don’t want to acknowledge this. Let’s just take the worst case situation for Russia: they lose the case with the Katyń families, which then proves that any Soviet crime committed deserves reparations. You’ve got 25 million Ukrainian families whose ancestors were murdered. All of a sudden Russia collapses under the weight of trying to pay the reparations that these families will possibly want. And therefore Russia is very, very scared.

I get why they don’t want to deal with this head-on. They know that if they do, they will lose and then they’re going to be liable.

And then in that same forest there may still be more graves – and there are also probably graves in Belarus and Bykovnia.

Kiev, Ukraine

A couple of months ago they thought they found that fifth grave in Belarus – though it was proven not to be true. But it’s still out there. People know there is one, they just don’t know where. The numbers don’t match.

There were other officers murdered in Kiev, most likely thrown into Bykovnia, where they have done some exhumations and they have found some Polish officers. It just hasn’t been made an “official” Katyń gravesite.

It just keeps going, doesn’t it?

The more you dig, the more you find, the uglier it gets.

You go to Russia in the film. As Poles, we sometimes forget that there are everyday Russians living there who were just as oppressed – or more – than we were. Your interactions with your driver and his sister show this great humanity.

It was beautiful. The driver became extremely curious about [Katyń] – so we gave him a little lesson about what happened, who was involved, what the stories have been, what the truth is. It was great not just for him but for us to see this other side.

Particularly for my [Polish] guide, who does many trips to these places many times a year. It was really good for her also to begin to consider that there’s this other side to this story that perhaps doesn’t need to be sympathized with but needs to be empathized with and need to be considered.

At the Katyń conference in Washington DC in May, Zbigniew Brzezinski said that changes in the basic relationship between people begins not with formal treaties or reconciliations but changes in feelings, in attitude. Watching you interact with the Russians in the film – it just seemed very natural.

It did and it was. The true issue is the political one. As soon as Russians begin to understand what really happened – they have a certain amount of empathy at that point.

Optina Monastery, Kozelsk, Russia;

Site of one of the prison camps.

The downside is still that political side where you begin to see the other interactions come into play. And it’s a much bigger picture than them saying, we’re sorry. It’s much more involved than them just saying, here are the documents. They can’t do that without exposing all kinds of other issues and problems. Thus the story is so complex.

Russian TV broadcast Wajda’s “Katyń” after the Polish plane crash. And the government has put documents about Katyń– that the West already knew about, of course – on a government website. Those are interesting signs.

It’s a good thing that that happened – hopefully to finally quiet their own people about this issue. One of the people I interviewed – that’s not in the movie – continues to believe it was the Nazis who committed this crime. And this is an educated man in England.

It’s very healthy for the Russian government to be doing this. They need to push it out even further.

What was it like to be at the gravesites?

There’s many stories about the gravesites. The most famous is that birds don’t even chirp in the trees, it’s that quiet.

The birds do chirp in the trees there. But there is a certain feeling there. It’s indescribable but it’s a heavy emotion. You can feel the weight of what happened. Whether it’s the souls of the departed, or the evilness that occurred at that point – I can’t say for sure, but there’s definitely something. And everyone feels that – it’s not necessarily connected to somebody who has someone there. It’s a heavy place.

You added footage of the plane crash to the film. A sad epilogue to the film, but somehow I have the sense – and I wonder if you do – that the crash was a very tragic way for the world to know more about Katyń.

Absolutely. I mention in the film how it took the sacrifice of another 95 people for the world to be made aware of this tragedy. Perhaps their sacrifice is the one that will erase the perversion of truth. It certainly seems that way so far.

One of the gentlemen in your film wonders [about the repatriations] whether Russian authorities are waiting for all descendants to die, but I thought, our generation will pick it up. We’re not going to let this die. We’re still here.

hat’s certainly the hope. Hopefully there’s enough of us out there that will pick up the reins and do something.

Katyń, Russia

This guy asked me a few years ago during the [research] interviews: What do you want to accomplish? At the time I was really bent on this whole history angle. And I said, I know I’m not going to change any history books in Russia. But it would be great if I could change a few in the United States. I still hope that in one respect, or at least to have this understanding that what we’re taught in school is not the be-all, end-all. That it’s just the jumping off point. That there’s more to these stories than you’re being taught in school, and that you should go explore them.

The other piece was illustrated by another American who came to see the test screening. The first thing she said to me after the movie was, “I gotta go call my grandmother.” And she didn’t need to say anything else after that point. I thought, that’s great. I would love if that happened to everyone who came to see the movie. For people to realize – our older generation, they probably have not told you everything. You should probably go ask.

CR

Imagery

Courtesy of The Officer’s Wife