Looked at broadly down the recent decades Polish cinema undoubtedly has some sort of presence on the international scene, and the first name that springs to mind is likely to be Roman Polański. He’s internationally known; not only for his films, of course. And then maybe Krzysztof Kieślowski, particularly for his Three Colours. Then Andrzej Wajda and possibly Agnieszka Holland. After that it begins to get difficult, even for film-goers with an interest in more obscure “foreign language films” (to use the Academy Awards category). Unless, that is, you happen to be the kind of film buff who can name the top three Columbian directors of the last fifteen years.

Looked at broadly down the recent decades Polish cinema undoubtedly has some sort of presence on the international scene, and the first name that springs to mind is likely to be Roman Polański. He’s internationally known; not only for his films, of course. And then maybe Krzysztof Kieślowski, particularly for his Three Colours. Then Andrzej Wajda and possibly Agnieszka Holland. After that it begins to get difficult, even for film-goers with an interest in more obscure “foreign language films” (to use the Academy Awards category). Unless, that is, you happen to be the kind of film buff who can name the top three Columbian directors of the last fifteen years.

I shall be writing about a film by up-and-coming director Andrzej Jakimowski, who debuted with his first full-length feature Zmrużoczy (Squint your eyes) in 2002. The new film is called Sztuczki (English title; Tricks – in the sense of conjuring tricks). It’s an extremely intelligent, perceptive and amusing film with just enough feel-good factor to stay this side of sentimentalism.

I’ve recommended it on many occasions to Polish friends. I was charmed by it, and wiped away more than one tear. I want to describe the film and what I liked about it, but also to place it in its Polish context. A lot of praise has been heaped on Sztuczki and its director, and the film has won awards at numerous film festivals around the world.

Sztuczki (2007) was filmed in and around the post-industrial, decaying landscape of Wałbrzych, a mining town in Lower Silesia and tells the story of Stefek, a ten-year-old boy, whose father walked out on the family some years before. A few photographs are all the material objects that Stefek has left to link him to his father. When Stefek recognizes his father as the man often seen waiting on the platform of the local railway station he resolves to win him back with the dogged drive, determination and clear vision of a ten-year-old boy. Stefek does so by contriving to manipulate events.

His sister, Elka, is an ambitious young woman acting as surrogate mother for her younger brother during the hot, summer months of the school holidays. Elka is determined to be taken on as PA to the Italian managing director of a foreign company with a shiny new building on the outskirts of town.

One of the great achievements of the film was to pull off the challenge of building the story around a young child lead actor and his relationship with his older sister without the film descending into mawkishness. It would be easy to do, considering the film focuses on family ties and the longing of a young boy for his absent father. But the family love Jakimowski shows us is practical and straightforward – quite unsentimental.

Elka’s relationship with her younger brother is shown convincingly. Stefek annoys her, as every ten-year-old boy with a twenty-year-old sister ought to. Elka is practical and strict with her younger brother, but Stefek has a resilient character, with a strong streak of independence and bloody-mindedness. He knows how to set about achieving his aims, sister or no sister.

The Wałbrzych of the film is gritty and depressed. And the traces of the Communist years are present at every step. You can see it in the metal grating over shop windows. It’s in the handcart that a tramp piles up with used bottles to get a few coppers for. In the old man’s pigeon-loft. And it’s not only the material culture of Communism, but the customs of those times, too. The father goes down to the river for a dip on a sweltering day – no aqua-park here. And then there’s the man selling a few kilos of apples grown on his działka (allotment) in front of the hypermarket with his own set of scales.

I first came to live in Poland for a couple of years in 1988; right at the tail-end of Communism. Many Poles, when they hear me mention that year, make a bit of a face and say, “Oh, yes, but you only experienced the lite version of Communism.” That may be so, but for a person brought up in “Western” Europe it sure as hell made an impression on me. I don’t intend to dwell on that here, only to say that the images in Sztuczki constantly remind me of those years. I sensed that Wałbrzych, the town forming the film’s backdrop, is still deeply lodged in those years.

And it’s a fact that those years are still deeply ingrained in a large proportion of the Polish population. I saw it recently when a middle-aged, portly woman felt the need to put on a spurt of speed to beat me to the front of a queue in a food store. That’s the imprint of Communism left on her.

In Sztuczki the shiny new office building and the foreign manager are classic images of modern Poland. The building is a smart, characterless steel and glass cube. Next to it there is a car park with a red block paving surround. Back in the bad old days of the late 80s I used to feel contempt for the uneven, broken slabs along Katowice pavements. But when I gaze at endless identical pedestrianised streets of red block paving in Polish town centres I get a sense of nostalgia for those old grey slabs.

And the Italian manager. He is part of the new ex-pat corporate community in Poland. These men and women rarely speak Polish, and are reliant on their PAs and translated documents to make contact with Polish reality. They’re similar to the British ex-pats in the colonies during the days of the British Empire. Physically present in another country but at the same time somehow not completely there.

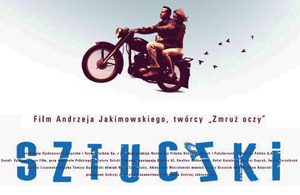

One more thing I’d like to mention. I was somewhat astonished by the choice of the photograph for the film’s poster. What it supposed to represent? Is it the Polish version of the Motorcycle Diaries? It certainly looks like the poster is advertising a road movie. The main character in Sztuczki is Stefek, and he’s not on it. Instead, a less important character – Jerzy – is depicted in a dynamic, resolute pose heading with certainty and determination towards a goal. Elka sits passively behind him, clutching him around her waist, being carried along with him. This is an image from Jerzy’s story – but Sztuczki is Stefek’s – and to a lesser extent Elka’s – story.

I would highly recommend this film on its own merits, but for viewers with an interest in Polish culture and history Sztuczki is a rich source of imagery of a town and community which in some ways have been left behind during the waves of economic revival since Poland first extricated itself from Communism and then became a member of the EU.

CR