All photos save Synagogue (#8) courtesy of Sławomir Nowosad

In the southeast of Poland situated at the confluence of the Łabuńka and the Topornica rivers not far from the Ukrainian border there is an enchanting small city, Zamość, so perfect you could be forgiven for thinking its builders, motivated by vanity, prepared for a horde of future photographers.

Zamość was built to be a citta ideale (an ideal city), created according to the ideas of its patron, the Polish chancellor, Jan Zamoyski, who engaged the Italian architect, Bernardo Morando, to design it. But, although aesthetically the city is a Renaissance jewel, its creation was not a vanity project; the great Zamoyski was far above that. His ideal city was to reflect all the elements of a harmonious community: civic responsibility, education, cultural and religious diversity, education, security, and trade.

Jan Zamoyski (1542-1605) was a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman, a magnate of immense wealth who held many of the most important positions in the government of Poland. He was an important advisor to Polish kings, including the great Stefan Batory; and an ardent supporter of constitutional and parliamentary rule who vigorously opposed the absolute power then ascendant in the monarchies of Europe.

He believed that a Republic, including a Royal Republic such as Poland, would only be as noble and as strong as its citizens. Educated abroad, he attended the University of Padua where his views of civic life and its responsibilities were influenced by his studies of Roman Republican history. The city of Zamość, the citta ideale he founded in 1580, reflected these views.

A pragmatic man, Zamoyski ensured the fortifications were built to the best specifications of the time. Indeed, the fortress of Zamość withstood both the attacks of the Cossacks and the Swedes during their invasion, a period known as The Deluge.

Morando designed a city that would provide the infrastructure to support Zamoyski’s idea that a model city had to provide facilities for trade, education, and public participation.

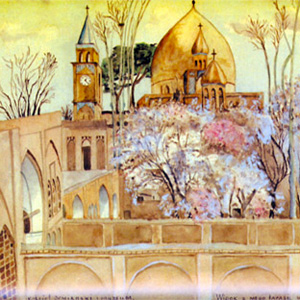

Zamość is built around the Grand Market square dominated by the town hall with its great winged staircase and clock tower. It was meant to be nothing less than a publicum forum, a place where the town would hold important public events. The town’s most important buildings framed this lovely square: besides the town hall there is the gallery of expensive shops with an arcaded promenade to provide sheltered passage in front of shops; two smaller markets, the Salt and the Water markets, were situated outside the centre of town.

Facing the square were the houses of the most important members of the business community, who came to live in Zamość at the personal invitation of the chancellor himself.

An ardent believer in religious freedom and cultural diversity, Zamoyski knew exactly what citizens he wanted and his invitations reflected this. Apart from his fellow Poles, he invited Armenians who came from Armenia, Turkey and Persia as well as from Polish cities where they had already established themselves. The “Armenian houses” still reflect the affluence and high culture of these first wealthy merchants of Zamość who also held high offices in municipal administration and in the university, and built their own church.

The second group to arrive were the Greeks, who brought with them their Orthodox branch of Christianity and were free to build their own church and maintain their cultural heritage.

The third group was Sephardic Jews who came to Zamość from Italy (probably because of Zamoyski’s time there as a student), Turkey and Spain. They prospered and in 1603 built a magnificent synagogue in the Renaissance style, still standing, as well as a mikva (baths) and a heder (a school).

The Akademia of Zamość, essential to the intellectual life of the city, was a lay school with three secular departments: law, medicine and liberal arts. Zamoyski established contacts with the great learning centres in England, Belgium, Holland, and Italy; brought in scholars such as the English jurist, William Bruce, and the Belgian mathematician, Adrian von Roomen; and arranged for students to study abroad. With a printing house publishing the outstanding works of the time, and Tintoretto painting for the Collegiate Church, citta dei, now the Cathedral, Zamość was as lively as it was lovely.

A Dutch scholar, Georg van der Does wrote about Zamoyski: “Nothing testifies better to his love of Poland than this town, which he raised from its foundations, leaving a remembrance of himself more lasting than the pyramids and monuments to Poland and to Europe…”

It has often been said that Poland has had “too much history,” and Zamość has had its share, though it was largely spared destruction. Today, it’s a UNESCO World Heritage site, a model of Renaissance architecture incorporating central European urban design such as the arcaded galleries. It is a lively cultural centre with art, music and several museums.

But to start, you can sip wine at a table on the sunny plaza and immerse yourself in the sheer beauty of the place, maybe imagining you are back in the 16th century, mingling with the merchants and intellectuals of the day dressed in the distinctive style befitting their cultural heritage and social position. It’s an ideal town for dreaming. And then catch a show at the Jazz Club Kosz.

CR

Was Zamosc spared intensive German bombing because Hitler admired and wanted to preserve its architecture. They say this was true for Prague and Odessa as well. Apart from Zamosc, Hitler seemed intent on pulverizing Poland.

Thank you for this! I want to visit Zamosc’. I used to live in Poland in the 80’s, when I was a student. Loved it!