Polish theatre has gained world renown thanks to its innovative and bold experimental style. In international theatre circles, it is often enough to mention the names of Grotowski, Kantor, Witkacy, and Gombrowicz to elicit profound nods of approval. One aspect of Polish theatre that is well known but rarely analyzed is that its greats often straddle many artistic disciplines. Kantor was both painter and theatre director, Witkacy was both painter and playwright, Gombrowicz wrote both novels and plays with equal ease. Drawing on that strength, Polish artists often blend many art forms, feeling equally at home in various fields and genres. Poland’s current most-renowned Renaissance man is Bogusław Schaeffer.

Polish theatre has gained world renown thanks to its innovative and bold experimental style. In international theatre circles, it is often enough to mention the names of Grotowski, Kantor, Witkacy, and Gombrowicz to elicit profound nods of approval. One aspect of Polish theatre that is well known but rarely analyzed is that its greats often straddle many artistic disciplines. Kantor was both painter and theatre director, Witkacy was both painter and playwright, Gombrowicz wrote both novels and plays with equal ease. Drawing on that strength, Polish artists often blend many art forms, feeling equally at home in various fields and genres. Poland’s current most-renowned Renaissance man is Bogusław Schaeffer.

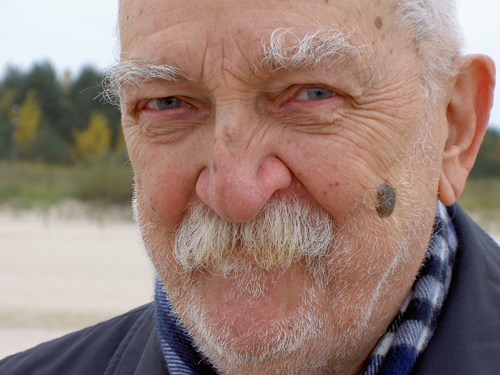

Eighty years old, Schaeffer is a composer of music, a music theoretician, a playwright, and a graphic designer. In 1999, to celebrate Schaeffer’s 70th birthday, the Jagiellonian University in Cracow organized a symposium devoted to his entire body of work. Not surprisingly, the speakers ranged from actors and theatre critics to musicologists and composers. Schaeffer’s oeuvre is beyond impressive. To date, he has created 550 musical works in 23 different musical genres, written 46 plays (translated into 17 languages, including Estonian, Hungarian and Hebrew), and designed about 400 graphic works. Schaeffer is the author of the first handbook of modern composition (no other composer has written as many music books as he), and a professor at the Salzburg School of Music and at the Academy of Music in Cracow. Widely regarded as a pioneer of “new music” and avant-garde theatre, Schaeffer is one of Europe’s most influential contemporary composers as well as the most frequently performed playwright in Poland today. He has been acclaimed as one of the most interesting artists of European culture in the last few decades.

Eighty years old, Schaeffer is a composer of music, a music theoretician, a playwright, and a graphic designer. In 1999, to celebrate Schaeffer’s 70th birthday, the Jagiellonian University in Cracow organized a symposium devoted to his entire body of work. Not surprisingly, the speakers ranged from actors and theatre critics to musicologists and composers. Schaeffer’s oeuvre is beyond impressive. To date, he has created 550 musical works in 23 different musical genres, written 46 plays (translated into 17 languages, including Estonian, Hungarian and Hebrew), and designed about 400 graphic works. Schaeffer is the author of the first handbook of modern composition (no other composer has written as many music books as he), and a professor at the Salzburg School of Music and at the Academy of Music in Cracow. Widely regarded as a pioneer of “new music” and avant-garde theatre, Schaeffer is one of Europe’s most influential contemporary composers as well as the most frequently performed playwright in Poland today. He has been acclaimed as one of the most interesting artists of European culture in the last few decades.

Schaeffer is as prolific as he is revered. His Klavier Konzert was featured in the soundtrack to David Lynch’s Inland Empire; Eugène Ionesco wrote Three Dreams in Schaeffer’s honor. Solo, a 2008 documentary film about Schaeffer, won the Grand Prix for art film at the 2009 Montreal Film Festival, for showing “an unusual journey to the roots of an even more unusual art.” In 2010, the film was screened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. In 2009 a chocolate was created in Schaeffer’s honor by Meister Hacker of Konditorei Confiserie Hacker in Rattenberg, Austria.

Schaeffer is as prolific as he is revered. His Klavier Konzert was featured in the soundtrack to David Lynch’s Inland Empire; Eugène Ionesco wrote Three Dreams in Schaeffer’s honor. Solo, a 2008 documentary film about Schaeffer, won the Grand Prix for art film at the 2009 Montreal Film Festival, for showing “an unusual journey to the roots of an even more unusual art.” In 2010, the film was screened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. In 2009 a chocolate was created in Schaeffer’s honor by Meister Hacker of Konditorei Confiserie Hacker in Rattenberg, Austria.

Schaeffer is the only composer in Western history with an independent dramaturgical career, and the only playwright with an independent career as a composer. In fact, in music circles he is often known only as a composer, and in theatre circles, only as a playwright. He is often called “the most prolific writer amongst composers and the most talented composer amongst writers.” It is thought that having two independent professions disrupts both of them, but Schaeffer defies this expectation. On the contrary, it seems that he is not only able to blend his music and playwriting career seamlessly, but to excel at each independently. How does he do it? Schaeffer famously described his living room with two desks: one devoted solely to music composition, the other to playwriting. As he says, he began writing plays as a respite from writing music. Playwriting, he says, is easy, compared with composing.

A universal artist, unafraid to explore a range of fields, forms, and subject matter, Schaeffer creates theatre that is guided by the rules of musical composition, and, like his music, it defies previous, established conventions and techniques, surprising its audiences with innovative and invigorating form and style. Schaeffer is what some call a conceptual composer, following the lineage of Mauricio Kagel, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Ernest Austin, and John Cage. His microtonal compositions are carefully structured and employ cyclical repetitions, and codes. Schaeffer’s plays exhibit similar characteristics: cyclical repetitions, episodic arrangements, and mathematical precision in their dramatic structure. Jerzy Popiela called Schaeffer’s dramatic structure “Schaefferismo,” a term borrowed from music and, in Schaeffer’s case, delineating a specific conceptual metatheatricality. Justyna Zając called Schaeffer’s dramas an example of the Instrumental Theatre, a term also borrowed from musicology.

A universal artist, unafraid to explore a range of fields, forms, and subject matter, Schaeffer creates theatre that is guided by the rules of musical composition, and, like his music, it defies previous, established conventions and techniques, surprising its audiences with innovative and invigorating form and style. Schaeffer is what some call a conceptual composer, following the lineage of Mauricio Kagel, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Ernest Austin, and John Cage. His microtonal compositions are carefully structured and employ cyclical repetitions, and codes. Schaeffer’s plays exhibit similar characteristics: cyclical repetitions, episodic arrangements, and mathematical precision in their dramatic structure. Jerzy Popiela called Schaeffer’s dramatic structure “Schaefferismo,” a term borrowed from music and, in Schaeffer’s case, delineating a specific conceptual metatheatricality. Justyna Zając called Schaeffer’s dramas an example of the Instrumental Theatre, a term also borrowed from musicology.

Used interchangeably with the term “spatial music,” the term Instrumental Theatre refers to various experiments with moving sound. Alexander Scriabin was a turn-of-the-century Russian symbolist composer whose experiments were part of a larger avant-garde trend of that time that favored experiments with movement, sound, and image. After Scriabin, Mauricio Kagel, an Argentine composer born in 1931, was the one who actually defined the concept of the Instrumental Theatre and who utilized its principles in his work. According to Kagel, in Instrumental Theatre the movement of sound must undergo constant and unexpected changes. The actions of the musician-performers are thus as important as the sounds they make. Following some of Kagel’s experiments with sound movement, Schaeffer has created a unique theatrical language in which the actor is viewed as an “instrumental medium.” The text sometimes suggests that actors can choose between different theatrical selves. Thus, the actors are constantly aware of the structural framework of each play and the relationship between the text, the movement, and the sound. In this arrangement, Schaeffer conducts his actors as he does his musicians.

Schaeffer’s most famous instrumental play is The Quartet for Four Actors. Since its premiere in 1979, the Quartet has been so successful that it has been staged by practically every Polish theatre. The premise of the play is simple: four male actors dressed in tuxedos mime a music quartet. The 25 episodic scenes are written with almost mathematical precision, which is juxtaposed with the men’s double-layered personalities. The actor-musicians balance between theatre and concerto. The play mocks the artificiality of TV language and the pretensions of the artists, who are unable to communicate with each other.

Schaeffer’s most famous instrumental play is The Quartet for Four Actors. Since its premiere in 1979, the Quartet has been so successful that it has been staged by practically every Polish theatre. The premise of the play is simple: four male actors dressed in tuxedos mime a music quartet. The 25 episodic scenes are written with almost mathematical precision, which is juxtaposed with the men’s double-layered personalities. The actor-musicians balance between theatre and concerto. The play mocks the artificiality of TV language and the pretensions of the artists, who are unable to communicate with each other.

Schaeffer’s next hit was Monologue for One Actor, which opened in 1976 in Cracow, with Jan Peszek, one of Poland’s leading actors, in the title role. The play has since been staged over 1,500 times around the world. In 1988 it was filmed by Polish Television Theatre. During its 40-year run, Monologue has been critically acclaimed and has won many awards, including the 1995 Grand Prix at New York’s Theatre Festival. Monologue, which is based on Walter Benjamin’s famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” addresses poststructuralist concepts of authorship and loss of creative agency. Benjamin, a German-Jewish philosopher and cultural theorist, argues that technology, particularly easy mechanical reproduction, diminishes the “aura” of art objects, dissolving their ritualistic aspect and erasing the very notion of “authenticity.”

In the transitional 1990s, Schaeffer became so popular that various cities started organizing so-called “Schaefferiads” – marathons of his plays, performed by various theatres in the space of a few days. Stanislaw Stabro notes that Schaeffer’s popularity in the 1990s was marked by the exhaustion of political language in drama, and by a return to Witkacy’s concept of theatre of the “pure form.” Giving up traditional dramatic elements and focusing on material aspects of theatre, Schaeffer draws not only from music, but also from commedia dell’arte as well as from carnival. Schaeffer is interested in language as a material, used for language games and as a means to parody the grand national dramatic models (Wyspiański’s Wedding comes to mind). Blending grotesque situations, absurd language, and dark humor, Schaeffer’s plays probe many questions of modern life, with humor and virtuosity. The fiction and reality of the stage constantly intertwine, suspending the heroes and the viewers in a no-man’s-land of ambiguous values and questionable intentions. In the transitional Poland of the 1990s, Schaeffer’s plays, always bringing in a paying audience, reflected the emotional and social conditions of the moment.

I began translating Schaeffer’s plays in 2001, intrigued by his popularity and his writing style. He sent me all of his plays and gave me full access to his manuscripts. Since then, we have maintained an active correspondence, and I have translated four of his plays. Schaeffer graciously appreciates the fact that I was able to capture the poetic, musical and playful quality of his writing. Most of all, however, he likes the fact that I “get” his peculiar sense of humor, since, as Virginia Woolf famously noted, “humour is the first of the gifts to perish in a foreign tongue.” The translator’s task with Schaeffer’s plays is complex. First, one must understand the script’s elaborate word games and puns. The plays are full of such linguistic gems as anacoluthons (rhetorical trick of changing syntax within the same sentence), solecisms (purposeful and playful grammatical mistakes) and intentional catachreses (misappropriation of words and sentences). These rhetorical devices are enough to give a translator a headache. But in addition to mastering the plays’ sociological, cultural, and linguistic context, one must capture their intricate musical structure: the rhythm and tonality of language. Finally, the translator must address the text’s visual arrangement: here, words are like notes; their order and page placement must be preserved. You don’t just translate; like Schaeffer, you must compose the play.

I began translating Schaeffer’s plays in 2001, intrigued by his popularity and his writing style. He sent me all of his plays and gave me full access to his manuscripts. Since then, we have maintained an active correspondence, and I have translated four of his plays. Schaeffer graciously appreciates the fact that I was able to capture the poetic, musical and playful quality of his writing. Most of all, however, he likes the fact that I “get” his peculiar sense of humor, since, as Virginia Woolf famously noted, “humour is the first of the gifts to perish in a foreign tongue.” The translator’s task with Schaeffer’s plays is complex. First, one must understand the script’s elaborate word games and puns. The plays are full of such linguistic gems as anacoluthons (rhetorical trick of changing syntax within the same sentence), solecisms (purposeful and playful grammatical mistakes) and intentional catachreses (misappropriation of words and sentences). These rhetorical devices are enough to give a translator a headache. But in addition to mastering the plays’ sociological, cultural, and linguistic context, one must capture their intricate musical structure: the rhythm and tonality of language. Finally, the translator must address the text’s visual arrangement: here, words are like notes; their order and page placement must be preserved. You don’t just translate; like Schaeffer, you must compose the play.

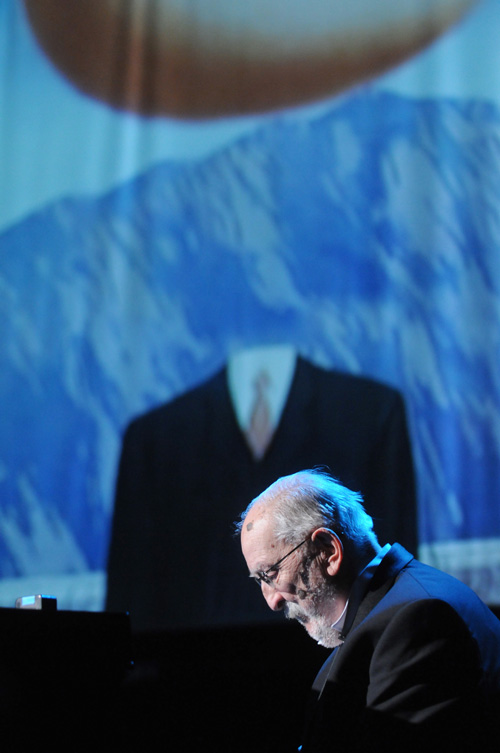

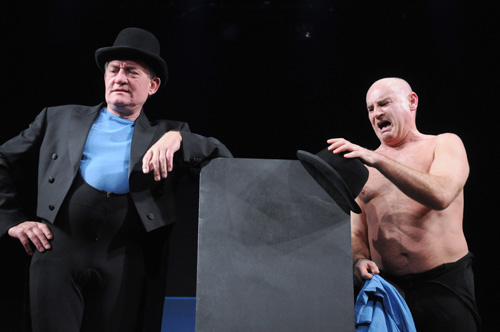

More recently, Schaeffer has become known on the international theatre and music circles for multimedia performances that include both his musical compositions and his dramatic texts. The most famous production is Schaeffer’s Era, an interactive audiovisual, multimedia performance that reflects Schaeffer’s own musings on contemporary culture, the art of composition and its perception. The show was created in 2009 by the Aurea Porta Foundation to celebrate Schaeffer’s 80th birthday. This brilliant multimedia improv gala features the Polish National Radio Orchestra conducted by Agnieszka Duczmal, the Olga Szwajgier Jazz Quartet, Bogusław Schaeffer on piano, soloist Urszula Dudziak, Schaeffer’s instrumental actors such as Marek Frackowiak, Witold Obloza, and Agnieszka Wielgosz, and Schaeffer’s play A Multimedia Thing. In 2010, an ambitious two-hour work was staged at the EICC as part of the Edinburgh Festival. Professor Richard Demarco, the festival’s co-founder, said he had “not seen anything like it from the times of Kantor,” calling Schaeffer’s piece “one of the best productions since the festival was launched several dozen years ago.” Both the Edinburgh Spotlight and the Herald Scotland awarded it 4 of 5 possible stars, calling it a “tremendous show in honour of an original talent.” The Edinburgh Spotlight wrote that “Schaeffer’s Era provides a rare and brief opportunity to be immersed in a compelling multisensory vision of a unique individual.” Schaeffer’s Era breaks down the barriers between a variety of genres, providing a bold vision of a true Renaissance man. The success of the original production prompted Aurea Porta to mount a second version, which is touring Europe to rave reviews as we speak. CR

Imagery

- Graphic by Bogusław Schaeffer

- Photo of Mr. Schaeffer by Krystyna Gierłowska

- Photo of Mr. Schaeffer from “The Multimedia Thing” by Tytus Żmijewski

- Stage performance from “Schaeffer’s Era,” courtesy of Aurea Porta Foundation

- “The Multimedia Thing” performance; photo by Tytus Żmijewski

- Stage performance from “Schaeffer’s Era,” courtesy of Aurea Porta Foundation

Pingback: • Bogusław Schaeffer, b. 6 June 1929 | On Polish Music

Pingback: Bogusław Schaeffer: Poland’s Renaissance Man – Magda Romanska