|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

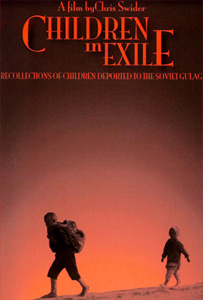

Children in Exile: Recollections of Children Deported to the Soviet Gulag

Opus 27 & BulletProof Film

© 2007 Opus 27 Productions

Writer & Director: Chris Swider

Producers: Chris Swider & Ilko Davidov

The winner of the 2011 Amsterdam Film Festival Van Gogh Award for Best Human Rights Film was Chicagoan Chris Swider for his documentary, Children in Exile. The film fascinated me when I first saw it, and I decided I very much wanted to interview Chris for CR to learn more.

Chris made the film because of his own personal connection: His father, a medical doctor, survived a gulag labor camp in Uchta.

Chris traveled to Uchta, today in Komi, part of the Russian Federation, in 1991. There, he found his father’s file in the city archives. In the file – a photograph taken by the NKVD (Soviet secret police) of his father.

When I spoke with Chris about the film, he said that the moment he held his father’s file in his hands was extremely emotional. “In the picture, he’s younger than I was at that time,” says Chris – younger by about a decade. “We photographed the whole file.” He also took his father’s photo (“they don’t need it anymore,” said the friend who accompanied him).

He also interviewed people in Uchta: Some were Polish, others weren’t, but most were either former prisoners or descendants of prisoners unable to go back.

“That initial run of collecting materials began the whole thing,” Chris says. Already a successful filmmaker, screenwriter and teacher by the time he began production, he’d been telling his parents’ stories to friends for years. “And they’d say, my God, you have to make a film about this.”

For his subjects, he selected people who were 18 or younger when they’d been deported. They tell the story. There’s not a single expert testimony, historian, or authority in the film. Beyond the introduction, which uses archival footage to introduce the war, everyone that speaks does so from first-person experience. The result is a candid and deep look into what it was like for children who experienced the horrors of the gulags.

There’s plenty of history in the film ¬– necessary context that explains the intricacies and complexities of those times, historical and political and social intricacies that may partially be the reason these stories aren’t as well-known as others.

For example: midway through the film, an important event layers even more historical complexity. On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacks Soviet Russia, its former ally. The Soviets need fighting men and sign a pact with the Brits and the Poles called “the Amnesty,” a farce really, considering the Poles had never committed a crime. The condition is that Polish men who want to get out of the gulags can join (or rejoin) the Polish army and fight the Germans. This proves nearly impossible in execution, because the men (and their families) need “freedom papers” from the Soviet police, a permit to travel, and papers for disinfection to get out of the Soviet Union. Chris’ father was “amnestied” – view a map of the journey he took to join the Polish Army below.

The film explains these complexities carefully, but it’s not meant as a lecture, Chris says. “It’s supposed to be a film with an emotional basis, constructed to be felt and experienced.”

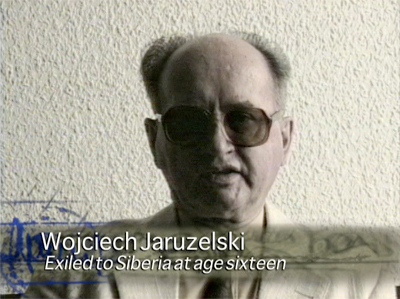

One of the most startling interviews is with Wojciech Jaruzelski, the last communist leader of Poland, who was exiled to Siberia at the age of 16. When he comes on screen, I immediately think of the now-iconic footage of him announcing martial law in Poland in December 1981. But there he is, talking about the difficulty of the day of his deportation, June 14, 1941, when Soviet soldiers declared him an “undesirable social element.”

He speaks characteristically: clipped words, short phrases. Deported to Kazakhstan, he describes it as “Beautiful. Sparsely populated. Mountains. Forests. Taiga.”

A friend of Chris’ had interviewed Gen. Jaruzelski previously, and helped set up the interview.

“I had a snap decision when setting up the camera,” Chris says, because the general was sitting by the window and thus partially lit, with half of his face in shadow.

“I could’ve moved the chair over so that his face was brightly lit. I decided to leave it alone,” Chris says. “I second-guessed myself about that a million times. In the end I’m glad I went with my intuition – to leave it that way, to suggest the mixed character he definitely is.”

He says that it’s one of the first questions he’s asked during screenings: Why is Jaruzelski in the film? When the film was screened in Poland, the parts with him were cut out. But as shocking as his presence may initially be, it’s also a fascinating glimpse into the controversial figure.

“When Jaruzelski was deported to the Soviet Union he was a child, and not a war criminal, communist or traitor,” Chris says. “If he was any one of those things he became them later. And maybe in fact what happened to him in the Soviet Union was a contributing factor to what he became.”

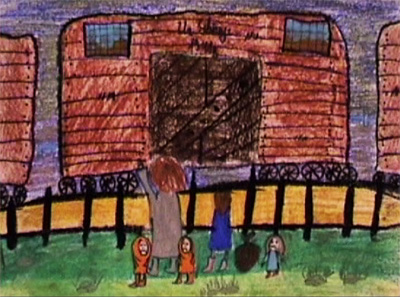

But the film isn’t just about Jaruzelski; there are other, poignant, vivid stories, in which trains figure prominently. The deportees were shoved into cramped trains, resembling cattle cars, to travel incomprehensible distances to the gulags: thousands and thousands of miles.

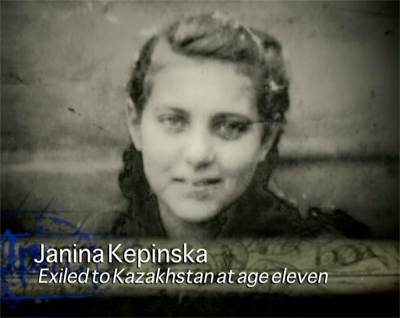

Janina Kępinska, 11 when deported, describes how there were 48 people in the train car that took her and her family to Kazakhstan. There were no sanitary facilities, just a hole in the floor. Through which, disturbingly, the deportees could get a sense of how many had gone before them on these tracks, which were filled with unending stacks of human waste.

One of the toughest parts of the journey is when the trains pass the Polish-Soviet border. Mieczysław Wutke, 12, says it’s a moment he’ll never forget. Wesley Adamczyk’s train begins singing the Polish national anthem, but is told by the Soviet guards to shut up or be shot like dogs.

The journey to the gulags lasted, on average, a month. Many don’t make it. But those who survive are immediately put to work, regardless of their age. Seven-year-old Wesley Adamczyk learns that if you don’t work, you don’t eat – because he is an enemy of the people. So he and his sister gather cattle dung for fuel. For their work, the deportees receive “supplies” for the winter. Jacek Furdyna’s family gets two loaves of bread and a watermelon. That’s for the entire family, for the entire winter.

And beyond the hunger, cold, and lice, are rapes. Feliks Milan was 17 when deported, and says that not a day went by without rapes. The camp he was in had many criminal prisoners, who were cruel to the political prisoners with no consequences from the camp guards. They raped girls, boys, some until their death – in front of their families. He breaks down as he speaks: “Those pictures will stay with me until the end of my life.”

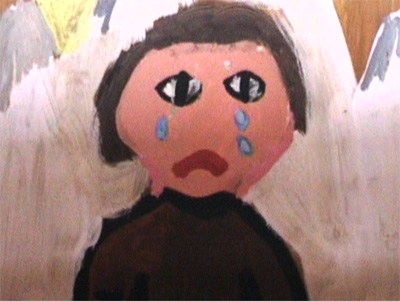

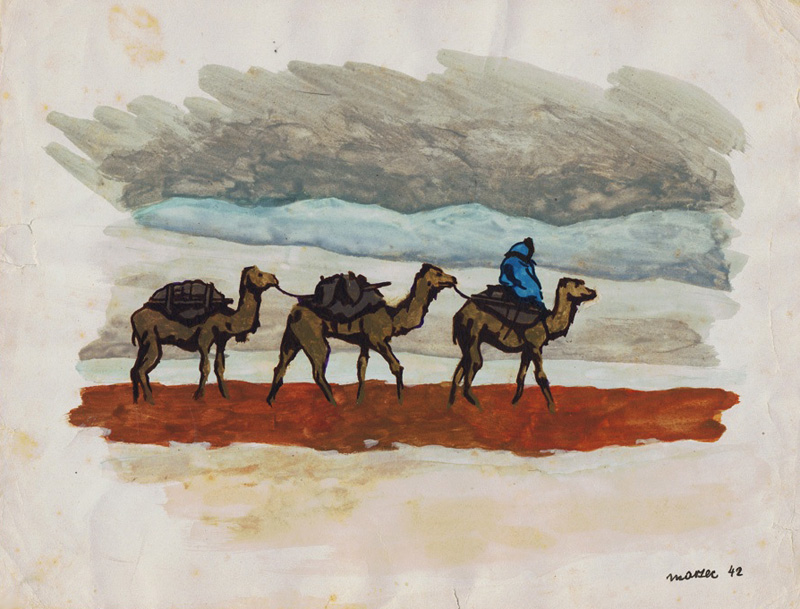

Apart from the interviews, the film’s emotion comes from drawings. Chris’ co-producer, Ilko Davidov, found a series of children’s drawings on a Latvian website. After Latvia withdrew from the Soviet Union, an educational campaign was initiated where older people would talk to schoolchildren about how they’d been politically oppressed. Just telling these stories would’ve landed them in jail two years earlier. But now, they shared them, and the children drew pictures based on those stories.

Other artwork shown in the film was made by adult survivors. “That of course is done by people who have a greater skill level,” says Chris, “but it has a much-digested quality. Whereas works by kids and teenagers has this emotionally raw quality.”

I ask Chris how he was able to draw out the interviewees’ to speak about their experiences.

“The people I interview were the selection of that population who wanted to talk,” he says. “It’s to some degree a distorted view. Those people had an inordinate amount of fight in them.”

That’s obvious in people like Zygmunt Stachowicz, deported to Siberia at 17. He was arrested but tried to escape; for that he was beaten nonstop for two weeks so that his clothes are soaked with blood. Then he was forced to work in a gulag almost to the point of death. But he fought to stay alive.

“There was no way that the wounds they had were going to heal,” says Chris. “And nobody understood them.” Those who survived and went back to Poland were met with little understanding. People wondered why, if the camps were so awful, people had survived. Maybe they were spies? “That’s the final punishment of these people,” says Chris. “They can only verbally find solace among themselves.”

From the individual, powerful stories in the film, one much larger is formed: that of justice and human rights.

Chris has shown the film in 28 film festivals, and it’s won 8 awards, including Best Documentary Film Under 60 Minutes at the San Luis Obispo International Film Festival in 2008. He’s sold the film to libraries and institutions – “I want to sell more,” he says; the project was largely self-financed. He’d also like it to be broadcast more, but admits there are difficulties. “For North American audiences this is a subject matter that finds little resonance and interest,” he says. Others see the film and ask why they’ve never heard about these events before. And still others “think the Iron Curtain fell, the Berlin Wall is down – and this is all over,” says Chris.

But for him – and for the survivors – it’s not over. Because human injustice goes on.

“If you look around, the world offers us plenty of misery,” he says. Why focus on this one? “You have to make an effort to stop injustice on a case-by-case basis,” he says, “and call for justice on a case-by-case basis so that some of these things can be corrected.”

This belief is echoed by Feliks Milan in the film’s conclusion. He speaks of Ethiopia and Cambodia and places where human rights continue to be trampled, often without repercussion. That, he says, is the greatest evil. Those crimes must be confronted, “otherwise others who commit crimes against humanity will think they are without responsibility.”

He also speaks of the children – the children who we’ve seen in archival photographs throughout the film, successively thinner with each frame until they’re walking skeletons, each rib visible, their tiny legs just skin and bone.

“During the deportations of 1939 – 1941, in those cattle cars, infants died in their mother’s arms. Mothers died holding infants,” says Feliks Milan. “This is the greatest tragedy. Who today remembers those children?”

Imagery

Courtesy of Opus 27 Productions

* * *

CR highly recommends this documentary for screening and broadcast purposes.

We also encourage you to buy copies of this film and donate them to libraries and institutions.

Learn more about the film and contact the filmmakers at their website.

This map details Chris’ father’s journey from the moment of his arrest in 1939 through his immigration to England in 1947.

In 1939, Konstanty Swider was a captain in the Polish Army Medical Corps and a PhD medical doctor of neurology and psychiatry.

He was arrested by the NKVD outside of Lvov (A) (then Poland, today the Ukraine). Sent to a Gulag labor camp in Uchta (B), he initially worked as a lumberjack but then got a job as a doctor so that he could work inside, which is probably what saved him, according to Chris.

When the Amnesty came in 1941, he found his way south to where the Polish Army under General Anders was mobilizing: from Uctha across the Caspian Sea (C), then through Iran (D), Iraq (E), Palestine (F), Egypt (G).

He was a doctor at the famous Battle of Monte Cassino (H), where Polish troops successfully defeated German and Italian troops.

His wife and Chris’ mother, Maria Baranowska Swider, had survived the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. They were reunited in the town square of Verona (I) – yes, the Verona of the Montagues and Capulets and the eternal love of Romeo & Juliet. They immigrated to England (J) in 1947 and moved to the U.S. in 1951, when Chris was six months old.

His father continued working as a doctor, but had to first intern and spent five years in residency in a New York hospital. He died in 1965. He never returned to Poland.

CR

Here is the story of another child in exile

http://thedailynews.cc/2011/12/07/howard-city-woman-recalls-time-in-russian-labor-camp%E2%80%A8/

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption

Pingback: Welcome to our Spring 2015 issue!

Pingback: Isfahan, the City of Polish Children