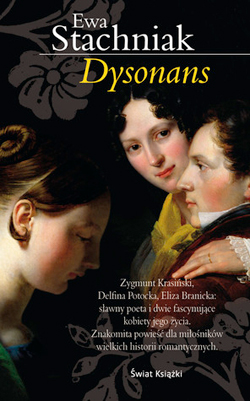

A fragment from Dysonans, a novel by Eva Stachniak

A fragment from Dysonans, a novel by Eva Stachniak

… life is simply one huge dissonance….

—Countess Delphine Potocka to Frederick Chopin, Aix-la-Chapelle, 16 July 1849

Countess Delphine Potocka, a Romantic muse to a number of prominent artists: Frederick Chopin, poet Zygmunt Krasiński, and French painter Paul Delaroche. An artist in her own right — a talented opera singer who sang for Chopin on his deathbed — she held regular salons in her Parisian apartment, where Chopin was a frequent guest.

Just a few of my closest friends, Delphine calls it, dropping by at the end of the day. In fact, by midnight, her small salon is filled beyond comfort. Guests are crammed into every available space. Squeezed on the ottoman, perched on the window sills, leaning against the doorframes. Josephine, the maid, is sighing in exasperation, casting her worried glances. Even the bedroom chairs had to be brought in and they are so fragile that Delphine fears they might break under a stouter gentleman. She has instructed Josephine to get slim ladies to sit in them.

Charles de Flahaut is walking toward her, and Delphine hasn’t even noticed his arrival. Handsome and haughty, black eyes, narrow face, a white cambric shirt cradling his neck scarf. Around him a crisp whiff of horses and misty meadows and an aura of significance. He wears it well. It makes men seek him out, hang on his heels. Wait for an opportunity to make a move.

From across the room, her sister Lusha flashes her a playful glance. Delphine remembers the time they had given themselves a moustache with some burnt cork. They put on their brothers’ trousers and their chemises, tied neck kerchiefs under their chins and hid their hair under Papa’s beaver hats. Thus dressed they appeared in the Kuryłowce salon to Maman’s gasps of horror.

Comte de Flahaut takes her hand in his and kisses it. She hasn’t seen him for two years, and the closeness is pleasant. Oddly dreamlike, dim, abruptly tempting.

“Delphine,” he says. “I couldn’t resist.”

Frederick is standing by the piano, his thin, limber figure slightly bent. Around him, as always, the women flock. It is at his request that Princess Marcelina detaches herself from Lusha and agrees to play. Her teacher’s request, says Marcelina, is her command.

This is a welcome development. Anything that saves Frederick’s strength is good. Marcelina hesitates for a moment before deciding on the Second Ballade. Delphine is fonder of it now than she used to be. When one is young, she thinks, loss means so much less.

Lusha is smiling at her from across the room, sending her a kiss on tips of her fingers. Delphine moves from one group of guests to another, light and attentive.

“We are all wanderers longing for home,” Prince Czartoryski says, leading her toward the far corner of the salon and thinking her a fine woman. A very fine woman. Tall and slender, her eyes shining as if she were a girl of sixteen, out for the first time in her life.

Delphine thinks that the old prince is holding well for his seventy-five years. His old age is bony and austere. Not an inch of flesh on his body that is not absolutely necessary. No one among them can equal him in stature or position.

The true Polish King in exile.

Prince Czartoryski confesses that all the talk he hears of Poland’s martyrdom, of a speedy return to a resurrected motherland worries him. He can accept the call for spiritual transformation, but in whose hands and to what goal?

“Have you heard the latest,” he asks. “Mickiewicz had a vision of Napoleon raising his hands to the heavens. Repentant, weeping over the fate of Europe.”

The Ballade glides into a siciliano, transforms itself into an etude, explodes into a diabolical waltz. Marcelina has made tremendous progress. Her pianissimo is exquisitely subtle.

Prince Czartoryski is not listening to the music.

In Mickiewicz’s latest vision, he tells Delphine, Napoleon, his face covered by a white veil, begs humanity for forgiveness of his weaknesses and announces that the one who comes after him will carry his mission forward, the way it was intended. A vision confirmed by the miraculous recovery of the poet’s wife and by the luminous tail of Faye’ s comet.

Potocki, Prince Czartoryski thinks, is a scoundrel and a cad. (From this pretentious Tulchin palace he has heard some sordid accounts.) It’s a shame he thinks, such a proud woman. Never asked for anyone’s pity. Never.

“The one who comes after him is Towiański,” the Prince pronounces the name with a grimace. “No one knows anything about him, my dear. The man arrives in Paris and calls himself a prophet! I’ve heard he is a Tsarist spy. He wants us all to be at each other’s throat!”

Prince Czartoryski’s anger is palpable, youthful in its bristling, feline shape. He is trembling with indignation.

“Despair,” he says. “Visions are borne out of despair. Of poverty and hopelessness of exile. But there are dangers.”

“You are an inspiration to us all,” Delphine says, stopping the passing waiter with a tray of simple canapés (cucumber ones are the least expensive and Chevet makes them look elegant with slivers of parsley and pickles).

A canapé in his hand, having admonished Delphine for not eating enough (you will turn into a nymph my dear, he has said), the Prince is ready to make some concessions.

If one could forget this Towiański, Mickiewicz is right in insisting that Christian Europe has failed Poland. Allowed a dismemberment of a sister Christian nation. Participated in it, if one wants to be more sordid. He is right saying that, by this act of sacrifice, the exiled Poles have become the shadow on the conscience of Europe.

“Count Krasiński, I’m told, is of the same opinion,” the Prince says, clearing a breadcrumb from the corner of his mouth. “I hope he knows I’ve great respect for him.”

“He does.”

Delphine looks across the room to where the guests flock around the piano. It is Frederick, not Marcelina, who draws them now.

When Delphine came to him for her first music lesson Frederick asked her to watch him play. Everything mattered then, everything was a clue. His delicate slender hands, capable of covering wide stretches and skips with lightness that seemed to her magical. Playing black notes with his thumb! She watched how his left hand kept strict time, never letting his right hand, now hesitant, now impatient, depart from the rhythm. His touch. His secret.

This is what she was doing wrong, she thought then. Her outstretched fingers! Frederick respected that each of his fingers had a different strength, he explored these differences while she tried to minimize them. He didn’t care for level tones her other teachers insisted on. He was right.

He laughed as if he could hear her thoughts. “No,” he said. “Look at my hands, but do not stop listening.”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Delphine says. The room is growing quieter with anticipation. “No words. A genius has no need for them. Frederick Chopin!”

He thanks her for this introduction with a subtle nod of his head and a shadow of a smile. He sits himself on a rosewood piano stool, letting his body find the best position. Just the way he taught her, he is taking his time. Entering another world cannot be accomplished too hastily. First one must empty oneself of what is not music.

Delphine casts a glance at his elbows. If he keeps them close to the sides and plays only with finger touch, she will know he is weakening. Then she will insist on a break. She is his guardian angel, he sometimes says, and that’s what angels do. Once he told her that in every room they have been in together, she has left something of herself, something only he can see. A spot on the piano where her finger tapped as she talked to someone indifferent. A chair where she sat as he walked into the room. A flower vase from which he picked a bunch of camellias to give to her.

No one dares to move, waiting for the first breath of music to stir. When the chords spill into her small salon, silence deepens. He is improvising tonight. Under his elfish fingers Dąbrowski’s mazurka, the Polish anthem, resonates with the sounds of lost battles, gunshots and bugle summons. Harsh unforgiving chords rattle the piano, return with bitterness, demand attention, before scattering into a happy chorus of playful children.

In the salon in rue de Mathurins the guests bend their heads. Those who have heard him before know what to expect. Even before he starts they anticipate the memories of this moment which will remove them from this salon, this street, this city. Melt their resentments, fears, even their hopes. Those who hear him for the first time-and there are quite a few of them tonight-feel shame at the memory of their previous misgivings. Were they guilty of calling his modulations hard, inartistic? Full of ear-splitting dissonance? Did they really doubt all that fuss around this sylvan Pole?

Wiping off tears from her cheek, lost in listening, Delphine has forgotten to look at his elbows.

“Bravo, Bravo! Encore! Encore!”

Josephine makes a sign of distress, a hand raised, a frown. The time has come for dessert, small bowls of fruit ices decorated with mint leaves. Marquis de Custine has sent three crates of his best champagne. This is an unexpected treat, for most Parisian hostesses offer much less. The arrival of champagne, bubbly in long glasses (like the waiters and the two kitchen helpers on loan from Chevet) is greeted with applause. As always, her friends say, Countess Potocka is an exquisite hostess. (“I agree,” Charles Flahaut whispers into her ear.)

Lifting the champagne glasses, they drink the health of the genius who has played for them and the hostess who has made the evening possible. On Delphine’s repeated insistence, they also drink the health of the generous Marquis de Custine. He thanks them with a benevolent nod of his head, not letting his eyes off Frederick who gives him wide berth and averts his eyes if they accidentally lock with his. Not because Frederick does not like the Marquis, but because he detests all flamboyance, all display of desire, all hint of carnal lust. Frederick Chopin does not like hearing that the divine Marquis has lost his heart to him, a second Pole in a row.

A remarkable evening. Something is in the air, some giddiness, some latent joy. Delphine finds it easy to laugh, to exchange witty gossip. About Chateaubriand who believes he is growing deaf for he does not hear his name mentioned in other people’s conversations. About Princess Gavard grabbing the stub of Liszt’s cigar and swearing she would carry it in her bosom to the day she dies.

Behind Delphine, Comte de Flahaut whispers, caressing her elbow. Beware special missions, illusions of grandeur.

Nobody is chosen. Nobody is that important.

“Money,” he says before she leaves him. “You Poles talk of love and missions. Of eternity and the soul, but in the end you too are only human. You too marry for money.”

Delphine doesn’t know who proposes the game first. De Custine perhaps who wishes to draw Frederick’s attention to himself. Whoever it has been, the Marquis is now in charge of requests. “Our genius,” he says. “Our beloved Frederick has graciously agreed to amuse us. He will compose and play musical portraits of the people we know.”

Frederick obliges with a twinkle in his eyes. “Your portrait, my friend, will be first,” he says bowing to the Marquis who sits beside the piano, awaiting his fate. The notes that come are prancing with affectation, rising and falling without much of a reason. But just when the listeners are about to dismiss the music and the character in the portrait, dark pensive tones appear, and won’t let go. Beyond the irritating exterior, the music is saying, there is depth, there is an understanding of the darker aspects of life. Haunting understanding, impossible to dismiss.

The guests applaud in awe. The Marquis is wiping a tear from his powdered cheek. Jan, his Polish lover, repeats, “Kapitalne. Absolutnie kapitalne.” No one needs a translation, no one is going to disagree.

This too is the evidence of genius. This ability to encapsulate people’s character in a few notes. But of course it is not just notes. Frederick Chopin changes as he plays. His face takes on the subtle hints of the people whose soul he is capturing. As soon as he is freed from words, his whole body reshapes itself, grows or diminishes with music. When he was but a little boy he wrote on his father’s name-day card, “it would be easier for me to reveal my feelings if they could be expressed in musical sounds.” Already then.

A few other portraits follow. Sometimes Monsieur Chopin announces who the model is, sometimes he allows the guests to guess. Everyone guesses Duke d’Orleans, the military march broken with a dazzling swirl of a seductive waltz brought to an untimely end with a tragic, unexpected half note and left unfinished. Everyone guesses Comte de Flahaut, a cheerfully dissonant fantasy making its way through the swirls of accords, some delicate like petals, some harsh and prickly like thorns. Everyone applauds when he bows to Mlle Rothschild and offers her a cheerful, open, trusting fugue. A fugue which at the very end transforms itself into a solemn, serious echo of a more powerful chord preceding her.

“Please, dearest Frederick,” Marquis de Custine asks pointing at Delphine. “Now is the turn of our beautiful hostess.”

“Only if Madame la Comtesse will allow me,” Frederick says, bowing to her and placing the fingers of his open hand to his heart.

“Yes,” she says. “I will.”

There is silence when he stands up from the piano and comes up to her. In one decisive gesture, perhaps too sharp, he removes the shawl draped around her shoulders and throws it on the piano keys. Her portrait, he seems to be saying, he can play blindfolded, without having to look at the keys. I know you, he is saying, I know what’s hidden, what others are not allowed to see. What he begins to play is a joyful romp, a stampede, explosion of bells and giggles of delight. But soon, so soon, a darker, sinister tone appears, and then grows stronger, extinguishing the joy.

Why is the piano crying, Maman?

Delphine is aware of the looks her friends cast toward her. Furtive, embarrassed, for her portrait so strong at the beginning has become hesitant, lax. It stops in mid-chord, returns to the beginning, meanders softly, muffled, lame. She crosses her arms on her chest, missing the shawl, the gauzy protection she has lost.

Is this truly me, she thinks.

Her friend, her music teacher, the man who says he loves her for what no other man has loved and will love her, Frederick Chopin, stops playing to look at her, assess her confusion. And then they come, the first chords of Casta Diva from Bellini’s Norma, an invitation, a challenge worthy of her talent.

Norma? A proud priestess of the Druids or a woman betrayed, fighting for the right to love?

She moves toward Frederick, past her guests who make room for her. She rests her hand on the lifted cover of the piano. She sings, her voice even and assured, sliding from forte to pianissimo.

Her salvation?

Senza nube and senza vel… Everything in the aria points to these words, and they yield to Delphine without resistance. In the salon in rue de Mathurins something raises in the air at this moment, something sacred, divine.

Ah! Return to me beautiful

In your first true love;

I’ll protect you

Against the entire world.

Frederick looks at her with awe. Her voice and music, his eyes tell her, are one.

CR

Imagery

Chopin Playing the Piano in Prince Radziwill’s Salon, Henryk Hektor Siemiradzki, 1877