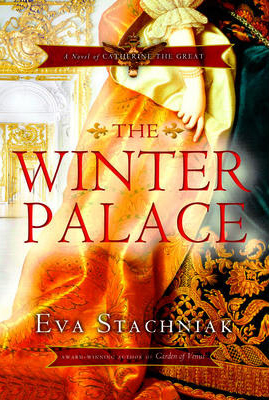

By Eva Stachniak

By Eva Stachniak

Doubleday Canada (2011)

The Winter Palace, the magnificent home of the Tsars on the banks of the Neva River in St. Petersburg, dazzles millions of tourists each year. Its baroque architecture and its sheer size – over a thousand rooms all sumptuously decorated and its museum, the Hermitage, housing one of the largest art collections in the world – make it a must for visitors to the city, be they serious art lovers or casual tourists on their all-inclusive two week tour of Russia.

They visit a museum. Do they think about it as someone’s home? Hard to apply that most charming of English words, “home,” to this grand edifice, but home it was, and not only to the Tsars. The court at the Winter Palace was also home to courtiers and their servants, to officials and imperial guards, to cooks and seamstresses.

All of them – from the Tsars and Tsarinas and their heirs, to the architect building the new palace, and to the lowliest of servants – make up the cast of characters in Eva Stachniak’s stunning new novel, The Winter Palace.

But first, the city. Built by Peter the Great with slave labour and at a cost of 200,000 lives, St. Petersburg moved the Russian capital closer to the West and was meant to rival the best of Europe’s cities. The Great Perspective Road, now the Nevsky Prospekt, with its palaces and churches, notably the Kazan Cathedral; Vasilievsky Island in the delta of the Neva River leading to the Gulf of Finland with its unusual and eerie museum, the Kunstkamera, The Winter Palace illuminates them all. Empress Elizabeth added to her father’s plans with her own monumental undertaking: the construction of a Baroque-style Winter Palace that would rival Versailles. Neither father nor daughter completed their projects in their own lifetime but both left an architectural legacy of majestic splendour, the essential backdrop for the Tsars – and for Stachniak’s book.

Eva Stachniak knows the city well, and her narrator moves about it with ease as she enters the Winter palace, first as an orphan, a “ward” given over to the care of Empress Elizabeth, and eventually as friend and confidante Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, a minor German princess, potentially the future bride of the Tsarevich, Peter, the empress’s nephew, and finally an empress in her own right – Catherine. The orphan girl, Varvara, will become a countess. But first, both the future countess and the future empress must navigate this dangerous journey with skill, stoicism, and daring.

Varvara is our narrator, and from the moment she enters the court, the pace is breathtaking, the sense of danger palpable. The reader is drawn close, caught in the decadence and the intrigue and dares not miss a single whisper. Plots, ambition, spying, treachery, flattery, conflict, fear. Trust no one, move swiftly.

Both girls are gifted, literate, speak several languages. They adapt. Sophie quickly realizes that German princesses are not likely to be popular, so she studies Russian assiduously and masters it. She must win over the Tsarina, so converts to the Orthodox faith and accepts a new name, Catherine.

The Polish bookbinder’s daughter is consigned to work in the Imperial Wardrobe. She attracts the attention of the chancellor, Bestuzhev, when delivering a dress to the empress’s chamber. He notes that she is clever, and fluent in Russian, German, French and Polish. Could be useful. He seduces her with a promise, instructs her in the art of deception: “Listen. Watch. Remember. Lie to anyone, but never to me and you won’t regret it.” Varvara learns, never looks back, advances her position.

The chancellor toys with her, but only briefly, for she would be wasted on mere sexual pleasure. She numbs herself to his advances, a small price to pay for securing a better position. In this, her position is no different from that of many others including the Palace guards who are routinely summoned to the empress’s bedroom. They don’t – can’t – refuse, but they know a reward will follow.

Still, Elizabeth had her favorite, the “Emperor of the Night,” a Ukrainian choirboy who eventually rose to a high position and was ennobled. Elizabeth forces a husband on Varvara who, despite her doubts, turns out to be an honorable man.

The empress rules by whim, power descending to the favorites who impose their will, in turn, on their underlings. There is no sentiment or kindness in the court, no love between lovers, no loyalty between friends, no protection from mothers.

Catherine’s position is precarious; the Tsarevich is more interested in alcohol and toy soldiers than in producing an heir. Nevertheless, Catherine produces a son – perhaps with an ancient method of assisted reproduction – but the empress sends a wet nurse to take the boy away from her immediately after birth. Elizabeth had her heir; Catherine was of no further interest to her. Betrayed by her mother, used by her mother-in-law, bereft of child, Catherine too learned to grow numb, and would inflict her own cruelties some day, sometimes willfully, often thoughtlessly. Power knows no sentiment. But she had a friend in Varvara, and may even have loved a couple of her lovers.

Three strong women dominate this tale, each with her own ambitions, her own plans, her own spies. It is a dangerous game but with great rewards if played well.

All this time wars are fought, territories expanded, allies betrayed. That, of course, is the source of real power; the court and the bedchamber are instruments to be used in the pursuit of power, when they are not merely entertainment.

Stachniak begins The Winter Palace with a fragment from a letter written by Catherine to the British ambassador in 1756:

Three people who never leave her [Elizabeth’s] room, and who do not know about one another, inform me of what is going on, and will not fail to acquaint me when the crucial moment arrives.

Was Varvara one of them? And who was spying on Varvara?

A marvelous novel, well researched, gripping, intriguing, suspenseful, leaves us wanting more. The good news is that Eva Stachniak is well on the way to completing the second volume, this one with Catherine ruling as the Empress of all the Russias. In this novel, Stachniak notes, “You do not reason with a flood, you look for anything useful that might float your way.” One can expect Catherine to be the tsunami to Elizabeth’s flood.