Kaia, Heroine of the 1944 Warsaw Rising

Kaia, Heroine of the 1944 Warsaw Rising

By Aleksandra Ziółkowska-Boehm

Lexington Books 2012

After decades of an almost eerie silence, in recent years there has been an explosion of books about Poles who lived through WWII, both under the German and the Soviet occupations. Many are being written by the children or grandchildren of wartime Poles, others are memoirs recently discovered and published by the younger generation. Some are literary gems, such as Edward Herzbaum’s Lost Between Worlds, discovered by his daughter Krystyna Mew, or The Long Bridge, written by Ursula Muskus whose grandson, Peter, brought it to the attention of publishers in Scotland.

These stories are stunning and it is little wonder that a younger generation is awed by the experiences of their parents and grandparents. The noted architectural critic, Witold Rybczynski, phrased it so well when writing about his parents in his book, My Two Polish Grandfathers: “It’s difficult for me to reconcile my childhood image of my parents – circumspect, cautious, to my immature eyes unadventurous – with these audacious individuals crisscrossing Europe, setting out into the unknown at a moment’s notice, and persevering in the face of one calamity after another.” He then notes that at his father’s age he himself braved “nothing more hazardous than departmental faculty meetings” and posits that the Polish talent for improvisation in life could explain the Polish love of jazz.

And yet, so many young Poles think that the past is boring, that Poland’s recent economic success is really the only thing of any interest. But humans are the only creatures who are conscious of a past; it’s almost against nature for us to ignore it.

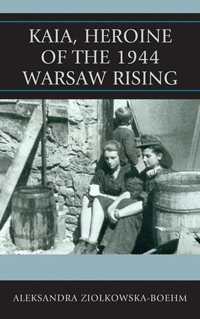

So it is with great pleasure that I see books coming my way, even if CR can’t review them all. Kaia, Heroine of the 1944 Warsaw Rising caught my attention in part because I have met one of the young women whose photograph is on the cover, and because Aleksandra Ziółkowska-Boehm is an interesting writer, and also because a much admired historian, Anna Cienciala, endorsed it.

One thing that immediately caught my attention is that although there is a generational difference between author and subject, the two are not related. Their bond was friendship, and over the course of 30 years, Ziółkowska-Boehm kept notes from her frequent visits to Kaia and their many telephone conversations, and she kept all of Kaia’s letters. As Kaia approached her 90th birthday, the author realized that her friend’s story had to be shared, and so began a final flurry of letters and telephone calls.

The title, Kaia, the Heroine of the 1944 Warsaw Rising, does not quite do justice to the story, which covers a much greater span of time. That said, there is no doubt that the signal event in the lives of what I think of as “the Generation of ‘44” was the 63-day uprising.

The book opens with Kaia’s childhood in Siberia, and here the reader is in for a surprise. Siberia, it is revealed, is more than a land of prisons and slave camps. It is a vast country of great beauty, rich in natural resources, and many Poles went there when Poland was still partitioned in search of a better life. Better educated than the local population, they established thriving communities, owned successful farms and other enterprises, and many Polish engineers worked on the Trans-Siberian Railway. True, for decades, the Tsarist regime had exiled thousands of Poles to this distant land and the exiles, once freed from confinement and still not permitted to return to Poland, found solace among their fellow countrymen.

The violence and ideology of the Russian revolution put an end to all that and the Poles fled back to their homeland, freed by Piłsudski’s Legions at the end of WWI. The weeks-long train journey home is an adventure in itself, and finally Kaia’s family settles near Wilno (Vilnius). Families are reunited, adults establish new homes, children resume school. Kaia, gifted both academically and artistically, chooses architecture for her career. A bright future awaits her and her interesting, animated, highly motivated friends.

The violence and ideology of the Russian revolution put an end to all that and the Poles fled back to their homeland, freed by Piłsudski’s Legions at the end of WWI. The weeks-long train journey home is an adventure in itself, and finally Kaia’s family settles near Wilno (Vilnius). Families are reunited, adults establish new homes, children resume school. Kaia, gifted both academically and artistically, chooses architecture for her career. A bright future awaits her and her interesting, animated, highly motivated friends.

In September of 1939 all that comes to an end. The double invasion by Germans and Russians, the cruelty under occupation, the dangers of underground resistance, and finally the horror and brutality of the 1944 Rising. Finally? Their ordeal was far from over. As the Germans retreated the Soviets entered, bringing their second reign of terror with them. Both occupiers focused on destroying the best and brightest, and so it continued. Kaia, and her surviving friends were once again hounded, arrested and sent to the gulag. And yet, she and her husband, Marek Szymanski, returned to a Warsaw in ruins and set to work to rebuild it. They had time for neither hatred nor self-pity. They worked, they traveled, and they enjoyed life, remembering everything but living very much in the present.

I heartily recommend Kaia, but add a word of caution. At first glance it can be daunting. The English is, at times, a bit awkward. Ultimately this does not detract, but instead evokes another time, another place. There are an awful lot of names to deal with and, nota bene, they are Polish names, many hyphenated names, and to top it off, then accompanied by wartime codenames.

But you don’t have to memorize them all; there will be no test. What you must note is the importance of these names and why the codenames are always added. Think of their importance to the conspiracy, to the safety of comrades, to years of knowing people only by their codename. These names can never be left out of a story.

Note also the social history implicit in the narrative. The friendships and the collegiality of the young men and women, the unquestioned equality, their mutual respect and affection; the value attached to education; the high spirits combined with a strong will; the love of freedom and the commitment to their society. It was a very special generation and Kaia is an inspiring example of it. CR

Imagery

- On the book cover, the dark-haired woman is Kaia.

- This photo from the book, courtesy of Aleksandra Ziółkowska-Boehm, shows Kaia and a friend, Tadeusz Łochowski, about a year before the war. How lovely and chic they are, how unsuspecting of the trial that awaits them.