“Lech – Lech – Lech!” The crowd chants as Lech Wałęsa, co-founder of Solidarity and former President of Poland, walks onto the Pritzker Pavilion outdoor stage in Chicago’s Millennium Park. He is the honorary guest here at “Freedom ’89,” a multimedia concert celebrating the 20th anniversary of the fall of Communism in Poland.

“Lech – Lech – Lech!” The crowd chants as Lech Wałęsa, co-founder of Solidarity and former President of Poland, walks onto the Pritzker Pavilion outdoor stage in Chicago’s Millennium Park. He is the honorary guest here at “Freedom ’89,” a multimedia concert celebrating the 20th anniversary of the fall of Communism in Poland.

I’ve seen Wałęsa in photographs and videos, but never in person. His hair, once dark brown, is now completely white, but he’s unmistakably recognizable. “Lech!” The audience cheers again and Wałęsa seems to channel this energy, speaking forcefully and quickly. He thanks the organizers and performers of the concert, which will showcase Polish artistry and feature the music of Fryderyk Chopin in various forms.

Wałęsa acknowledges America’s role in helping Poland achieve its freedom, and then says: “There were some who said we should have done more back then. I’m telling you that we could not have done more than we did.” The reaction to this statement is mixed: Parts of the audience applaud while others are silent. Wałęsa moves on and concludes by thanking us for attending.

His statement strikes me as a bit defensive. I’m here to celebrate, not criticize. But perhaps my celebratory intention is more symbolic of my generation—a generation on the cusp of the era that brought massive political changes toppling Communism in Europe; a generation reared in America and lucky enough to never know the difficulties of Communist Poland.

I was a child in the 1980s, barely able to grasp the meaning of Communism. I did understand that Poland wasn’t free and wanted to be. My parents participated in Chicago’s anti-Communist movement, and I attended demonstrations and lectures with them. I didn’t understand much, but I knew that what was being discussed was important.

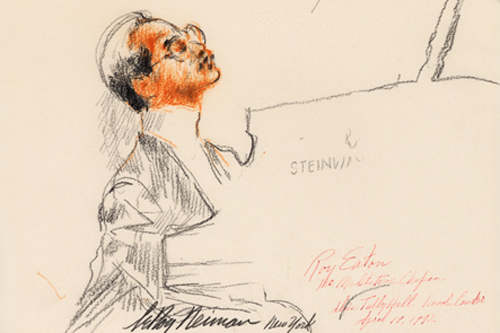

The audience this evening seems to echo my mood — here to acknowledge and celebrate. We all loudly applaud the first performer, Janusz Olejniczak, as he sits down at the black Steinway grand piano. Famous for his recordings of Chopin’s Piano Concertos with the Warsaw Symphony Orchestra, he was also featured as the hands — and performances — of Władysław Szpilman in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist.

Olejniczak’s performance is impeccable. As the notes of the first piece, Chopin’s Polonaise A-flat, drift over the crowd, a large screen above the stage projects a live feed of Wałęsa, seated in the front row. I think about how the Polish consulate, where anti-Communist demonstrations were held two decades ago, stands a few miles north of this very spot. And now, one of the main leaders of the Communist opposition is part of an audience of thousands, and we are all celebrating Poland’s freedom.

The screen shows the first of what will be a series of videos that will continue throughout the concert. We first see a smiling, white uniform-clad Stalin, then orderly rows of people marching past a tribunal decorated with a Polish eagle with no crown. (The Polish coat-of-arms bears an eagle wearing a gold crown; the eagle was portrayed crownless from the time of the Soviet takeover of Poland in 1945 through Polish independence in 1989.) A banner reads, “Czynem naprawimy nasze winy i błędy” (“We’ll fix our faults and mistakes through action”). I wonder what sorts of faults the Soviets proscribed onto this post-war Polish populace, still reeling from the effects of the war. The marchers walk on, stone-faced, as the video ends.

The second live performer is jazz pianist Leszek Możdżer, who will play “Improvisations on Chopin” of his own composition. Możdżer walks onto the stage holding a white cloth, which he places across the front of the Steinway’s strings. The resulting sound is a delightful cross between a player piano and a zither. Upon finishing this piece, he glances up quickly and almost immediately dives into the second piece while the crowd is still applauding. The screen shows his fingers flying over the white keys, juxtaposed against the dark blue of the Chicago dusk. I am simply awed by his performance.

As he plays, his profile is completely hidden by his shoulder-length blond hair. At one point he pauses for a microsecond to flick back his hair with both hands—then seamlessly resumes playing. After the second piece, he looks out into the audience, seemingly more at ease now, and offers an enormous smile before beginning his third piece.

Next, the musical group “Rock Loves Chopin” accompanies the Folies Dancing Company in various Chopin-themed numbers. They are joined at times by Polish tenor Leszek Świdziński, Polish vocalists Anna Serafińska and Jan Król, the PASO Chorus, and Chicago-based Polish dance ensemble Wici. Serafińska is especially impressive; her vocals are powerful and flawless.

The videos throughout these performances show Poland in the 1970s and 1980s. When General Wojciech Jaruzelski, Prime Minister of Poland from 1981-1985, comes onto the screen, the audience boos. Jaruzelski, a staunch Communist, imposed martial law in December 1981, claiming it was necessary to prevent a threat of Soviet invasion. The Soviets, he believed, were unhappy that the democratic opposition was gaining power in Poland and threatening to overthrow Communism. He assured the Soviets that the Polish (Communist) military would quell this opposition. Thousands of arrests — and around one hundred deaths — followed. One such death was Jerzy Popiełuszko’s a Catholic priest and outspoken anti-Communist who was beaten and murdered in 1984 by Communist agents. We watch footage of Pope John Paul II praying at Popiełuszko’s grave.

The next video montage is that of a bus with a handmade sign reading “Głód” (“Hunger”) next to Poles waiting in long lines for provisions during the severe food shortages of the martial law period. The camera pans to empty shelves. These videos are black and white, exactly how I picture what life must have been like at that time—devoid of any color. Tanks roll down streets as police in riot gear stand at the ready; tear gas and water hoses are turned on the crowds. But the grainy video also shows images of hope: Two teenagers run holding a Polish flag while a Solidarność (Solidarity) banner hangs from nearby windows.

The combination of rock music and videos and dance is unsettling at times — I tend to mainly focus on the videos, but every once in a while a dancer is lifted up or leaps and it’s startling to suddenly see a muscular, live leg against the bleak imagery on the screen.

The audience rises during the first notes of “Żeby Polska była Polską.” Many Poles treasure this song, written in 1976 by Jan Pietrzak (words) and Włodzimierz Korcz (music), as a hymn of the anti-Communist movement. Its title, taken from the refrain, means “So that Poland can be Poland.” Intrinsic in this hymn is the belief that a Communist Poland was not, and could never be, a true Poland. As audience members sing along with the refrain, it’s clear that tonight’s celebration is part of the process of Poland becoming and being itself. As Poles, we can now reflect on and share the events of years past. And we can also celebrate our present and future.

The next set of videos show the Berlin Wall. A child beats at the wall with a rock, then is picked up by her father, who holds her up so that she can peer through an opening in the wall. The camera looks through this opening into West Berlin. The child looks like she’d like to crawl through—into the new future.

The final performance features “A mury runą runą,” written in 1978 by Polish singer Jacek Kaczmarski. The lyrics are strong and hopeful: “The walls will fall and bury the old world.” The music, adapted by Kaczmarski from a melody by Catalan singer Lluís Llach, is mournful yet melodic.

I saw Kaczmarski perform this song in Chicago in 1983; I was 10 and my brother was 7. When our parents told us that we’d be attending Kaczmarski’s concert and meeting him, we excitedly listened to the album with this song over and over again on our small cassette player. We also made a card on which we drew a tall wall made of gray bricks on one side. The other side showed this wall in ruins, and a Polish flag flying proudly overhead. We nervously presented the card to Kaczmarski during intermission, when our parents took us backstage. He thanked us and smiled, peering down at us through his glasses. I remember thinking that his eyes were terribly sad. The scene in my mind is quiet and intimate — just us and him. Tonight, I join a crowd of thousands in singing the refrain of his song.

The final video imagery — a sailboat; an ancient castle; a thick forest; craggy mountains; a field of purple crocuses; a busy town center — is colorful and vibrant, showing Poland today.

Once the concert concludes, a small section of the audience remains, singing the refrain of “Żeby Polska była Polską”. The night is clear as I walk out of the park.

CR