One of the first “official” maps of San Francisco, 1849, drawn by Aleksander Zakrzewski, a veteran of the 1830 November Uprising who came to San Francisco as a political exile

November 2013 marks the 150th anniversary of the founding of The Polish Society of California. The occasion was observed by a grand celebration at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco, a venue chosen in part because it was there that some of the first meetings of the United Nations were held in 1945. Poland had not been invited to participate, an irony not unnoticed by at least one distinguished UN guest who, as will be revealed below, ensured that Poland would not be entirely forgotten.

But this year, the event was not a meeting but a celebration aptly titled “From Pioneers to Silicon Valley,” providing perfect bookends for the multi-volume history of Poles in California. Those first pioneers were talented and exciting people: writers, cartographers, physicians, lawyers, engineers, businessmen and, of course, the celebrated actress, Helena Modjeska.

Today, there is a strong Polish presence in Silicon Valley. Along the way Andrzej Poniatowski, the great-nephew of the last king of Poland, brought the first hydroelectric power lines to the Bay Area, established the Sierra Railroad Company, and formed the Standard Electric Co., now Pacific Gas & Electric; Modjeska’s son, Ralph Modjeski, became one of America’s greatest bridge builders.

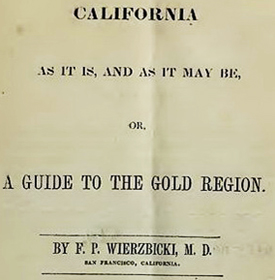

Cover of “California as it is and as it may be” by Feliks P. Wierzbicki, 1849

It was the first book printed in English in California.

The “Polanders” threw themselves wholeheartedly into American life, grateful for the opportunities afforded them but also remembering the loss of freedom in their homeland that sent them into exile. One of the first was Feliks Paweł Wierzbicki, a prominent member of the California Medical Society, who is best known for writing the first book published in English in California: California As It Is And As It May Be (1849). That same year, Aleksander Zakrzewski (ex-Polish officer) drew one of the early “official” maps of San Francisco that hung for a time in the Mayor’s Office.

In 1863, Polish residents of San Francisco held monthly at the Russ House, welcoming all supporters of Polish liberty. The Russ House was located at 235 Montgomery Street, and stretched from Pine to Bush Streets.

In May 1863, the Polish pioneers in California formed the first Polish organization on the west coast inspired by the January 1863 Uprising against Russia by the citizens of Poland. Headed by Kazimierz Bielawski, a civil engineer and surveyor, and five executive officers, among them a farmer, three merchants, and the rabbi from Congregation Beth Israel, these men were determined to assist the countrymen of their homeland to regain their freedom. Their monthly meetings took place at the Russ House at 235 Montgomery Street. The Russ family (Rienski) arrived in California during the gold rush, and Russ became one of the city’s “most respected assayers.”

At Platt’s Music Hall at 220 Montgomery Street (today the Mills Building), a “Grand Mass Meeting in 1863 won Americans’ support for Poland’s January 1863 Uprising.

Having established a Society, these patriotic pioneers quickly convened a “Grand Mass Meeting in Favor of Polish Freedom and Nationality.” Held at Platt’s Music Hall, the convocation was attended by civic leaders and dignitaries — a “who’s who” of 1863 California that included three future mayors, two future governors, two future U.S. senators, the publishers and editors of four daily newspapers, and legislators, industrialists, bankers, and merchants too numerous to mention.

It was a dynamic and colourful community. One of them, Captain Rudolf Korwin Piotrowski, co-founder of the Polish Society of California, was the inspiration for Sienkiewicz’s Trilogy character, Zagłoba. Colonel J.C Zabriskie, the first Sacramento City Attorney, raised funds for the Polish uprising, as did Charles Meyer who belonged to both the Polish Society of California and the first Hebrew Benevolent Society. In 1882, the Polish Society printed in local newspapers a condemnation of the anti-Semitic persecutions then taking place in Russia.

It was a dynamic and colourful community. One of them, Captain Rudolf Korwin Piotrowski, co-founder of the Polish Society of California, was the inspiration for Sienkiewicz’s Trilogy character, Zagłoba. Colonel J.C Zabriskie, the first Sacramento City Attorney, raised funds for the Polish uprising, as did Charles Meyer who belonged to both the Polish Society of California and the first Hebrew Benevolent Society. In 1882, the Polish Society printed in local newspapers a condemnation of the anti-Semitic persecutions then taking place in Russia.

As the years went by, the Polanders assimilated into the mainstream of American society. Immigration waned during the early part of the 19th century, not to be resumed in significant numbers until after World War II.

Among the first post-war immigrants was Stefan Norblin, whose Art Deco paintings in pre-war Poland and whose wartime paintings in India have recently been rediscovered and celebrated in exhibitions and film. He settled in San Francisco with his wife, the popular Polish actress, Lena Żelichowska.

1973 bottle of Warren Winiarski’s Stag Leap Cabernet Sauvignon; image via the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Some Polish Americans moved to California as well, among them Warren Winiarski. A Chicagoan by birth, Winiarski had gone to Italy in the 1960s to study Machiavelli and returned to America inspired to make his own wine. Soon after he moved to Napa Valley, north of San Francisco. There he tasted a wine that gave him his “Eureka” moment: it had what he described as both a regional and a universal character. Within four years he produced a red wine, a Cabernet Sauvignon, which won top honors at the historic Judgment of Paris in 1976. Nobody expected a California wine to beat out the French, least of all the French judges themselves. In a blind tasting, Winiarski’s Stag’s Leap Cabernet Sauvignon won, and the French had to live with their judgment – which they did, but not without sour grapes. And so it was that Warren Winiarski – surely a name destined for just this kind of victory – established his Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars on par with the world’s best, and put California wines on the map. It’s doubtful that you could buy a bottle of 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon these days but you can have a look at one at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

And history moves on. This anniversary celebration was well attended, including a contingent of the new Polish pioneers, the engineers of Silicon Valley. The celebratory crowd drank a toast to the many generations of Poles in California, and to those still to come. Sto lat!

Logo of the Silicon Valley Acceleration Center; a new exciting U.S.-Poland project

And so, 68 years after the historic meeting of the United Nations that excluded Poland, the Fairmont Hotel was the site of a much happier gathering of a new wave of “Polanders.” Once again both the American and the Polish national anthems were heard, and it was time to recall the man who had not remained silent in 1945.

It was none other than the great pianist, Artur Rubinstein who had been asked to play at the inaugural concert. As he subsequently wrote in his memoir, he was acutely conscious of Poland’s absence, and deeply distressed:

Artur Rubinstein on the cover of WISDOM magazine, March 1957; portrait photo by Karsh of Ottawa

“I walked on the stage, quite composed but with my heart beating… to play the Star-Spangled Banner [as required]… When I finished, I stood up to announce my first piece and something strange happened; a blind fury took hold of me. I addressed the audience in a loud, angry voice. ‘In this hall where the great nations gather to make a better world, I miss the flag of Poland, for which this cruel war was fought. And now — I shouted — I shall play the Polish anthem.'”

“I played with a resounding impact and very slowly, and repeated the last phrase with a resounding forte. The audience stood up as one man when I finished and gave me a great ovation.”

CR

Does a recording of Artur Rubenstein playing the Polish national anthem at the United Nations conference exist? If so, it should be preserved either here or somewhere for posterity.

An excellent question — I wonder myself. Time for some sleuthing!

This is so sygnificant It needs to go in front of american audience several times and include hollywood

Pingback: The Korwin Letters: Send Books!

Was a recording found?

We have not yet located a 1945 recording of Artur Rubinstein in San Francisco.