Wesley Adamczyk survived deportation to Siberia and exile to chronicle that journey in When God Looked the Other Way, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2004. His father, Jan Adamczyk, was one of tens of thousands of Polish officers killed in the Katyń massacre.

Over the years, Adamczyk, a tireless activist on behalf of Polish history, has collected memoirs and mementos of the Polish children in exile in Iran, India and Africa, including children’s autograph books. A few are shown below; their descriptions are located at the bottom of the article.

1940

It is spring 1940 and the world is more than a year deep into a war that will last five more. Wesley Adamczyk is 7. He has sandy blond hair and large blue eyes, and loves listening to his father tell stories about knights and ancient battles. Some days, Wesley likes playing hide-and-seek with his sister.

NIGHT OF DEPORTATION; Wola Piłsudskiego, Poland

From the diary of Wanda Barbara Kociuba, deported to the Soviet Union with her family in February 1940.

Courtesy of Wanda Barbara Kociuba

But not on this day, because he is on a train eastbound out of his Polish homeland. He tried packing his toys and books, but the soldiers said no. And so he huddles with his mother, sister and brother in a crowded train wagon with no seats or sanitation or food, hurtling toward Kazakhstan.

When they arrive, they’ll spend the first day of more than 700 in a Soviet forced labor camp. For weeks and months on end, they will almost freeze and nearly die from starvation. They are only one Polish family out of countless others being deported to Siberia as the war rages on. During the worst, coldest, hungriest winter days, Wesley dreams of home. And of food. He also dreams of his father (all the children do), and their reunion. They haven’t heard from him, or of him, for a long time. But it’s wartime, and they’re deep in Siberia. Thinking about their father sustains them.

Captain Jan Adamczyk, Wesley’s father, is 47.

Or, was 47.

The same spring that Wesley is hurtling toward Siberia, the body of his father lies in a mass grave with tens of thousands of other Polish officers in Katyń forest, deep in Russia. He has – like everyone lying next to him – a single bullet hole in the back of his skull.

Joseph Stalin and the entire Soviet Politburo signed the order for this mass execution in March 1940. The April 1940 execution is a concerted Soviet effort to wipe out the Polish intelligentsia: the Polish officer corps includes lawyers, doctors, professors – anyone and everyone who is a university graduate, according to Poland’s conscription system.

There are multiple mass graves in Katyń forest. Some will lie undiscovered for the next three years. The one with Wesley’s father will not be found for 50 years. In the spring of 1940, no one – except for the executioners, of course – knows they exist. The Polish government-in-exile doesn’t know. The rest of the Polish army, scattered across Europe, doesn’t know. The families – the ones who are in the photographs still in the officers’ pockets and wallets – they don’t know. And so Wesley continues to dream about his father.

2010

Wesley is 77. His gray hair is pulled back into a small ponytail. He wears large, tinted sunglasses when he’s outside, and sometimes when he’s indoors. If he closes his left eye, he can barely see anything out of his right one.

COVER OF ZOSIA ADAMCZYK’S BOOK

Wesley’s sister, Zosia, carried this book with her through 12 countries. Their father bought the book for Zosia in Zakopane in 1938; it has a wooden cover.

Courtesy of the Adamczyk-Kaminski family

He’s been a widower for ten years and lives alone.

There’s a framed photograph in his living room – it’s the only surviving pre-war photograph of Wesley and his siblings. In the photo, Wesley is a tiny two-year old, wearing a light-colored coat and hat, holding his sister’s hand. Their brother stands in back of them.

This same photograph is on the front cover of Wesley’s book: When God looked the other way: An odyssey of war, exile, and redemption.

Published by the University of Chicago Press in 2004 with a foreword by acclaimed historian Norman Davies, it chronicles not just Wesley’s journey to and from Siberia, but his father’s.

Wesley had an awful time writing the book. “I quit for three years. I was crying, my wife is feeling sorry for me. I said, it’s not going to work.”

He came back to the book because he knew that without those very feelings, that emotion, it would be lifeless. And it’s anything but: “Many women say they cry,” he says, “men too but men don’t admit it.”

1943

Wesley is 10. He’s a bit taller and much thinner. He’s living in a refugee camp near Tehran with his sister Zosia.

They escaped Siberia with their mother the previous year.

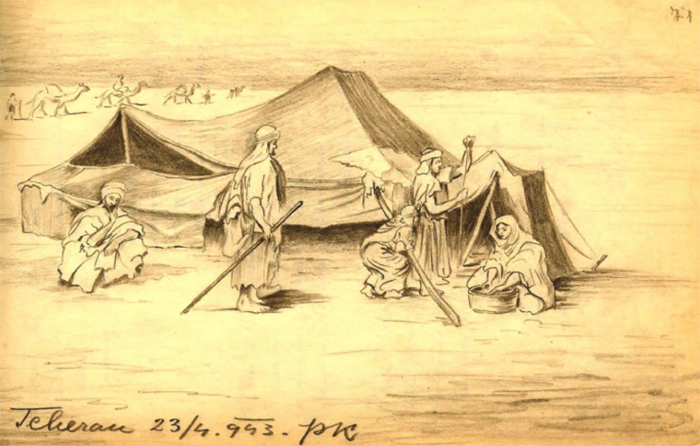

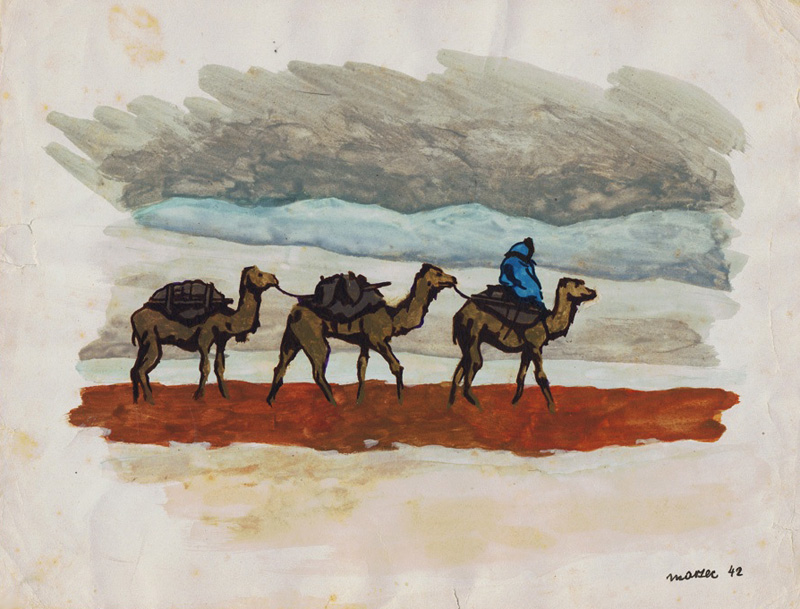

ARAB MEN IN THE DESERT; Tehran, April 23, 1943

By P. K. for Sabina Soltysiak

Courtesy of Sabina Soltysiak

As the war continued on and alliances shifted, Russia and Germany turned on one another. Polish leaders took advantage of this development, and approached Soviet and British authorities with a request and proposal: That the thousands of Polish deportees serving in forced labor camps in Siberia be allowed to join a reconstituted Polish army that would help Russia and the rest of the Allies fight against Germany.

The Soviets said yes. But Stalin made no provisions for these thousands – no food, no training. Polish leaders then asked the British army to take these masses under their protection. The British said yes. And so those Poles who survived began a reverse exodus from Siberia.

They were shipped to a British outpost in Tehran, where some died and some ended up in further flung outposts in India, Palestine and Africa.

Wesley’s older brother is in the Polish army fighting with the British, stationed in Iraq.

The three Adamczyk siblings are full orphans now. But they just don’t know it yet.

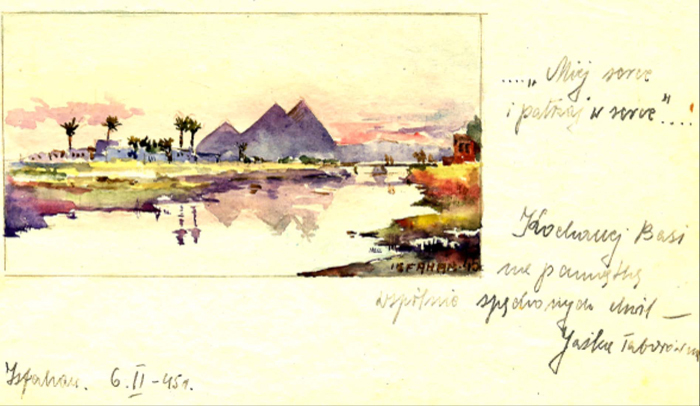

PYRAMIDS; Isfahan, Feb. 6, 1945

Inscriptions read:

“…In remembrance. Have heart and look into your heart…”

“For dear Basia, in memory of our time together – Jaska Taborowna”

Courtesy of Basia Kulikowska

They know they’ve lost their mother: Anna Adamczyk died in October 1942 of malaria and dysentery and exhaustion and a weakened heart. They weren’t there when she died, but were there when she was buried in a cemetery in Tehran. They’re still searching for their father, hoping that they’ll somehow find him.

But in April 1943, a mass grave in Russia is discovered by German soldiers; German armies have pushed deep into Russia by now. An international commission is called in to examine the graves and the bodies, which are wearing winter Polish army uniforms, coats, hats. They have all their personal effects on them: wallets, insignia, diaries, newspapers, photos, wedding rings. There are more than four thousand dead soldiers in the mass graves of the Katyń forest.

The commission’s investigation identifies the execution date – April 1940 – and the executioners: Russians. But Russia – officially Poland’s ally – denies responsibility for the Katyń massacre. They blame the Germans. They’ll continue their denial until 1990.

Wesley and his sister hear about the graves. But their father’s body is not among those found thus far. So they continue hoping he’s somewhere out there searching for them like they’re searching for him.

2010

ARAB WOMEN; Isfahan, Persia, 1943

From the diary of Wanda Barbara Kociuba

Inscription: “I am astonished that they (not the men) hold such heavy things on their heads. I am so excited to explore Tehran.”

Courtesy of Wanda Barbara Kociuba

At book lectures, Wesley often asks his audiences if anyone knows what it means to starve. Usually, no one does. “I say, in America you rush from school and you say, I’m starving! It’s a figure of speech.” So he explains what it means, because he’s lived it: Starving means you’ve had no food for a number of days; your stomach hurts; you lose weight; your gums are bleeding; you think you’re going to die.

He says he uses the word “imagine” but to please remember it’s only to a point that one can imagine. “In real life you can’t imagine unless it’s you.” He tried to write his book in a way that would help readers imagine as much as possible. It wasn’t easy.

“It’s so hard to put on paper what your heart and soul is thinking about,” he says.

1945

Wesley is 12. For a while, he and his sister lived in a camel stable on a desert near the Persian Gulf. Then Wesley is sent to a refugee orphanage in Tehran. His sister visits him there one day. She’s been to the British embassy and has been told that their father’s name was on a list of the Polish prisoner-of-war camps in Russia. All of these prisoners-of-war are missing. Some are accounted for: they’re the ones in the mass grave found by the Germans in 1943. But there’s still eleven thousand missing. Their father is one of them.

Soon afterward, Wesley escapes the orphanage to be with his sister in the refugee camp.

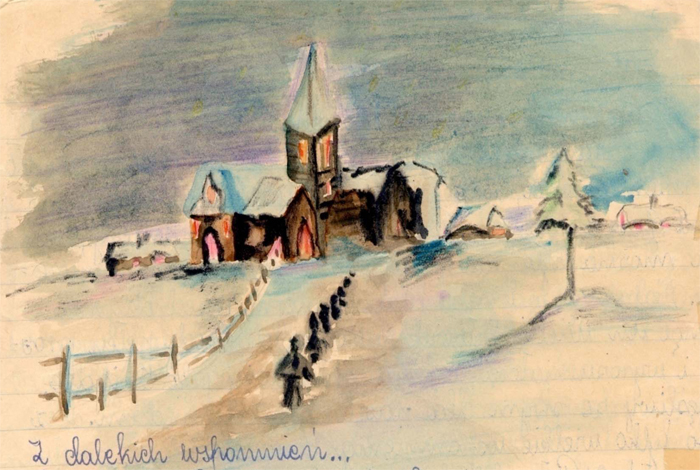

MEMORIES OF POLAND; painted in Zouk, Lebanon, Dec. 1947

From the diary of Wanda Barbara Kociuba; Kociuba was on her way to England from Lebanon in 1947 when she painted this picture, which she captioned: “Distant memories.”

In her diary, she writes, “But what of the memories – the truth has vanished. What happened to it all? Ah, it does not matter – because it will return – it will return, but then I will no longer be a child.” (Translation: Wesley Adamczyk)

Courtesy of Wanda Barbara Kociuba

And then the war ends.

Poles throughout the world – the Polish government-in-exile, Polish soldiers fighting alongside the Allies, Polish deportees and prisoners-of-war – all hope for one thing: to return to a free and sovereign Polish nation. But no such nation exists, because Poland is handed over to Soviet Russia by those very same Allies.

Wesley and his sister travel with other Polish refugees to Lebanon, where they’ll remain until 1948, when they’ll travel to England and be reunited with their brother.

The Soviets will continue to deny their responsibility for the Katyń massacre. In Soviet-controlled Poland, the official party line will always be that the Nazis shot all those Polish leaders in the back of the head at Katyń.

2010

The front of Wesley’s refrigerator is filled with overlapping notes, business cards, photographs. The lower third of his kitchen cabinets are in a similar state, with taped notes and business cards, drawings and scraps of paper with just a few words or sentences on them.

Wesley is often asked about the incredible amount of detail in the book.

“We have two types of memories,” he says. “Conscious and sub-conscious. The conscious – if you want to be a mathematician, you remember formulas. But there is a sub-conscious memory often hidden deep inside, of either powerful things that were tragic or beautiful things.”

1949 – 1990

Wesley is almost 16 in November 1949 when he leaves England for America on the British ocean liner Aquitania. It’s her last voyage with passengers.

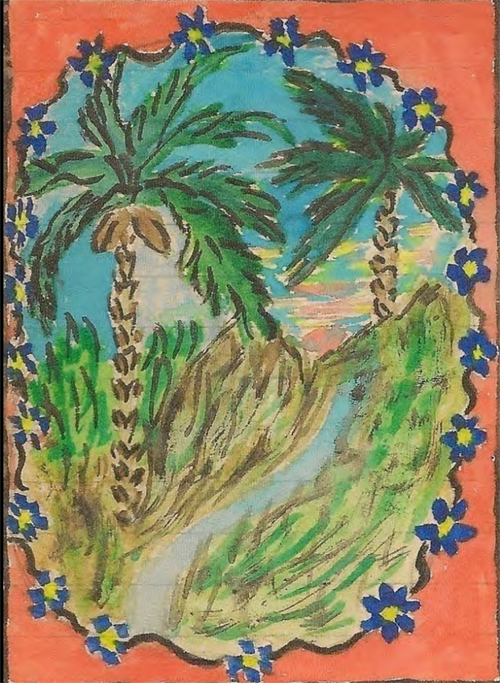

JUNGLE; Masindi, Uganda, Nov. 10, 1944

By Teodezja Platowna for Irena (Walaszek)

Courtesy of Irena Walaszek

He’ll arrive in Chicago on Thanksgiving Day and eat his first Thanksgiving meal at the home of his father’s sister. Three years later, he’ll graduate from high school. In 1957, he’ll graduate from college, then work as a chemist for Lever Brothers until 1995.

In 1989, Poland is finally freed. It’s the beginning of the end of the Soviet Communist bloc. The Berlin Wall comes down.

Wesley is 56 in 1989. In addition to his professional work, he’s an accomplished, semi-professional tournament bridge player. He’s married with one son.

In Poland, Polish Communist authorities lift the ban on publishing information about Katyń. No one at this point still believes it was the Nazis. Still, there’s been no admission from Russia – until April 1990, when Mikhail Gorbachev finally offers one. He also reveals the locations of the remaining, lost gravesites – in Miednoye and Kharkov.

Wesley’s father is in one of them. Captain Jan Adamczyk, born 01.21.1893 in Ciezkowice, Poland, executed in 1940 in Kharkov. The total number of Polish officers executed in the Katyń massacre is almost 22,000.

2010

Wesley has been asked why he didn’t write the book sooner.

“Simple,” he says. “Because for 50 years I was looking for my father’s grave and unless I found it, it would’ve been a book without an ending.”

The one chance he had at formal closure was 12 years ago when he traveled to his father’s grave with his son to take part in an international memorial ceremony. Wesley wasn’t sure in which of the mass graves his father’s remains were. So just to be sure, he said a prayer at each one.

Wesley’s latest project is a compilation of children’s memorial notebooks. They’re like American yearbooks, but with blank pages where children write poems and notes to each other. He’s gathered more than a 100 of these notebooks from Siberian deportees who were – like him – children during the war. Despite the horrors they saw – or maybe because of them – the children somehow managed to carry and preserve these notebooks. Wesley’s organized them into a powerpoint presentation, and clicks through it slowly, pausing at each slide to explain that notebook’s origins.

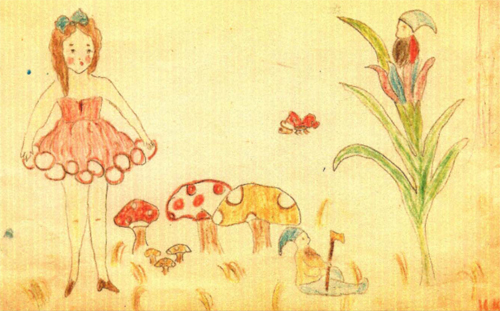

ELVES; Tehran, Sept. 11, 1943

This drawing depicts elves, or “krasnoludki,” magical creatures that live in the forest, says Wesley Adamczyk. Polish fairy tales describe these magical creatures as so tiny they sleep under mushrooms during the day. They work at night – and children know that’s why you can never find them.

By Krystyna Kolodynska for Zosia Adamczyk. Courtesy of the Adamczyk-Kaminski family

Childish drawings: A little girl stands by a mushroom with a bright red top with white spots; on another, fairies and elves. One page has real flower petals on it. They’ve lost their color, are brittle. More sophisticated drawings: a brilliant bouquet of flowers. A few green stalks with strawberries. An intricate bunch of violets.

Those who drew these had seen death, starvation, torture. And yet they were still able to make these drawings. “It’s encouraging. It’s hopeful. It’s beautiful,” he says.

He’s organized his presentation by country, and it moves from Russia to Persia, then Egypt, India, Palestine, Tanganyika, Lebanon, Uganda, England. He knows stories about each of the drawings and authors: “This was a friend of my sister’s in Siberia. Their mother died in Siberia, her two-year-old sister died in Tehran,” he says. “This girl lived in a tent with my sister in Tehran. We met again after 50 years in Chicago.”

His sister carried her own book through the 12 countries of their wartime journey. He likes reading the English translations of the notes and poems that accompany the drawings aloud: “Some people seek great happiness / Others for themselves seek love / I seek only to be remembered / Remembered in times to come.”

Like the faded, brittle flower petals, there’s a delicacy and sensitivity in the books that speaks to how those who drew them had witnessed horrors: “This girl’s sister froze to death in the Soviet Union in 1940.”

And perhaps because of the death that went hand-in-hand with these experiences, many of the notes are about remembrance: “Remember me,” “remembrance,” “a wreath of memories.”

“We all want to be remembered, don’t we?” Wesley says. “We don’t want to be forgotten. And that’s what it is all about.”

CR

Pingback: Chatting with Greg Archer

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption

Important and well-written overview about Wes Adamcyzk, his journey and remarkable book. Thank you, Justine, for contributing this.