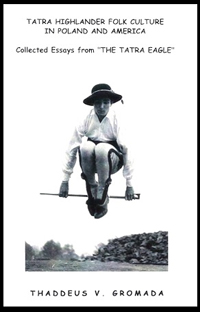

Tatra Highlander Folk Culture in Poland and America. Collected Essays from “The Tatra Eagle”

Tatra Highlander Folk Culture in Poland and America. Collected Essays from “The Tatra Eagle”

By Thaddeus V. Gromada

Hasbrouck Heights, NJ: Tatra Eagle Press, 2012, 173 pp.

Professor Thaddeus Gromada needs no lengthy introduction, since his many scholarly and organizational accomplishments are well-known in American Polonia. I myself have known Ted for a number of years as a historian and a leader in both the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America and the Polish American Historical Association. And yet I was stunned looking at the photograph adorning the cover of his newest book: a younger Ted Gromada, with excellent form, jumping over the ciupaga – no small athletic feat! So yes, Gromada can surprise and he can deliver – this time it is a slim, but important volume of essays, first published by him in The Tatra Eagle (Tatrzański Orzeł), the quarterly which he had edited with his sister Jane Gromada Kedron since 1947. The book is also dedicated to Jane, on the 65th anniversary of the quarterly.

I always considered The Tatra Eagle one of the best edited small publications in Polonia. Since it is bilingual, it appeals to both older generations of Polish immigrant górale, and the newer arrivals. It is informative and timely, well-written and illustrated, and with a sense of humor, so characteristic of the highlander culture. In the two brief introductory essays to the volume, Gromada comments on the history and mission of The Tatra Eagle, which the Gromada siblings started as teenagers. An important part of the quarterly had always been the essays authored by Thaddeus Gromada. Some of them introduced the history and culture of górale; a selection of them now constitutes Part I of the book, and highlights such topics as literature and poetry of the region, its legends, environment, politics, and educational prospects.

Other essays illuminated important individuals connected to the Podhale culture and situated their lives and works within the broader historical context; “Profiles of Eminent Personalities” are sampled in Part IV of the book, and include for example artist Stanisław Witkiewicz, Rev. Józef Tischner, Pope John Paul II, musician Andrzej Bachleda-Curuś, and composer Henryk Mikołaj Górecki. Written with scholarly expertise, but in an accessible style, these essays are a great read for anybody interested in all things Polish.

Parts II and III, however, fascinated me the most. The essays there focus on the family history of the Gromadas, as well as on the history of górale immigration to the United States and their community within American Polonia. As historians, we still know little about regional cultures, for example those of the highlanders, Kashubs or Silesians. Gromada tells a story of his parents and their staunch dedication to the maintenance and propagation of customs, language, and especially music of Podhale. Their cultural pride was inspirational to Ted, who wrote: “I have really been smitten by my Podhale heritage. There is something very fascinating and creative about this folk culture that should be shared and appreciated by all Americans of Polish descent and even Americans of non Polish background” (p. 5).

Ted’s father, Jan Gromada, was a talented violin player, designer and tailor of folk costumes, dancer, singer, as well as organizer and leader of music and dance groups, passionate about the literature and dialect of Podhale. Ted’s mother Aniela, in addition to caring for the family and working for wages, also performed in string ensembles, plays, and dance and music groups, while supporting other performers behind the scene by preparing food, and washing, cleaning and putting together their costumes. The author recalls how the family worked together and sang and danced together; the second generation becoming fluent in Polish and in the Podhale dialect. Jan Gromada’s Polish Tatra Highlander Music and Dance Group of Passaic, N.J., entertained a variety of audiences and presented splendid “Polish regional folklore in its purest and most authentic form” (p. 120).

Gromada also chronicles the history of highlander organizations, and especially these in the New Jersey and Chicago areas, including Związek Podhalan w Ameryce (Polish Highlanders’ Alliance of North America), and comments on the development of “Ruch Podhalański,” which is a regional cultural movement of Podhale. Gromada is optimistic about the future, when he remarks: “In this country we have the privilege of being fully American and at the same time, not losing our Polish góral identity” (p. 94). Gromada is far, however, from filiopietism. Occasionally, he casts a critical eye on some of the commemorative publications, and calls for a greater scrutiny in documenting the history of local organizations. This way he acts not only as a witness to and participant in the community’s development, but also as a professional historian. And, since his volume comes from a passionate góral as well as from a historical scholar, he points the way for others to continue both the propagation of, and the investigation into the vibrant, fascinating and rich culture, whether in Poland, or in America. I do hope that as Ted and Jane Gromada were inspired by their parents, their quarterly publication and the current volume will inspire others.

CR

And a CR note: That’s a young Dr. Gromada leaping for joy on the cover of the book.