The Long Bridge: Out of the Gulags

The Long Bridge: Out of the Gulags

By Urszula Muskus

Sandstone Press Dingwall, Ross-Shire, Scotland 2010

Preface by Kate Allen, Director, Amnesty International UK

Whereas the generation gap between war survivors and their children is often deep and wide, grandchildren seem to bridge the gap quite readily and easily. Peter Muskus, whose Polish father immigrated to England after his deportation to Siberia and subsequent service in the Polish II Corps of General Anders, developed an interest in his family history and his Polish roots at an early age, but it was his grandmother, not his father, who inspired and animated this interest. His admiration and affection for Urzula Muskus, the indomitable survivor of 14 years in Stalin’s Siberia, kept alive his determination to publish her memoir, The Long Bridge: Out of the Gulags.

It was a 30-year effort, for which every reader will be very grateful. Urzula Muskus, an intelligent and compassionate woman, wrote with great psychological insight and, because she was also a gifted writer, The Long Bridge is so much more than a personal memoir. For 14 years she observed the environment to which she had been condemned, and studied the society, as a whole and in its constituent parts. She describes the landscape, the prisons and the labour camps, forced “free” settlements in exile, the NKVD, the political prisoners and the hardened criminals that terrorized them, and the weary Soviet citizens everywhere.

The NKVD, Stalin’s internal security forces, were a familiar presence to all citizens of the USSR whether they were free or under arrest. With not a free-thinking man in the lot, the NKVD carried out their orders with brutal indifference. Rarely, and discreetly, one of them would show some kindness; Muskus never failed to note this because she believed that it was the system that was perverted and not the people. Despite all she lived through, she never lost faith in the basic humanity of all people.

Apart from the NKVD, the prisoners faced something much more terrifying once they were in the prisons and camps: the criminals. Sadistic psychopaths, these tattooed thugs raped, robbed and beat up the political prisoners with impunity: because the system was designed to terrorize the political prisoners into submission, the criminals were never discouraged. The gangsters’ molls, foul-mouthed, amoral and abusive, also preyed on the women prisoners, helping themselves to their food, clothing or any other possession they wanted. There was no defence against this. The thugs entered the barracks at will for sexual encounters with their molls, with total disregard for others around them.

The purpose of the Gulag was not merely to isolate and punish the prisoners; it was primarily a system of harnessing slave labour for the mines, forests, road and canal building, collective farms and any other industrial activity, mostly in the far flung regions of the Soviet empire. Working conditions were horrendous, dawn to dark, hunger was a constant, hygiene impossible, medical attention unavailable. Winter temperatures dropped to 40-60 °F below zero, summers swarmed with mosquitoes and flies. Many were quite simply worked to death, which was a matter of no consequence; more prisoners were always available.

And yet, Muskus did not really dwell on this. Her focus was on the friendships, the mutual aid, sharing scarce food, managing Christmas and Easter celebrations despite having nothing, singing hymns and familiar songs, encouraging one another. Nature was her greatest comfort and diversion. It is ironic that the Gulag, a creation of man, was set in a country of spectacular beauty.

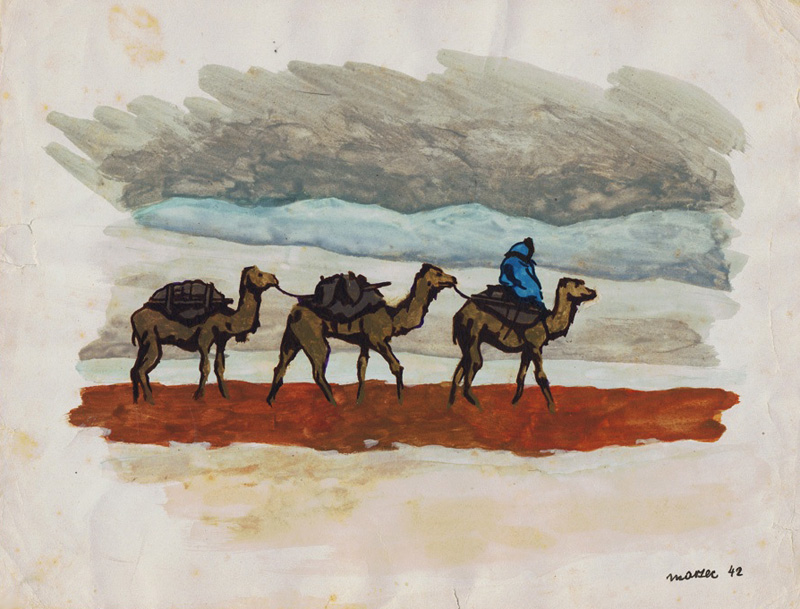

I have read many memoirs and talked to many survivors, including my mother, and noted how often people described the beauty of the landscape – mountains, rivers, lakes, the steppe, the forests, the deserts. For Muskus, as for many others, nature transcended the ugliness of the Gulag system and reminded her that the earth and the sky were eternal while the Soviet regime, with its warped theories and senseless cruelties, was transitory. “We regarded them as a transient evil, a physical, brutal power which must sooner or later wither away.”

But the first flowers of spring, the dawn, the sunrise, the sweeping vistas, and above all the sky, especially the night sky – Orion, Sirius, Pegasus, Andromeda, Ursus major, the Pleiades – the constellations were a constant, a magnificence beyond anyone’s control. She studied them; they inspired her. Over the years she had gained a powerful sense of internal freedom. “Mere oppression cannot imprison thought.”

In the 14 years that followed her deportation from Poland, Urszula Muskus had seen ordinary Soviet life, settlements of forced exile, collective farms, prisons and camps, and, when she was finally released from prison, it was to “freedom” as only the Soviets could define it: resettlement to yet another distant place of permanent exile. Hers was a fate shared by millions, people from all classes, from many European and Asian nations, Christians, Buddhists, Muslims, Jews, non-believers. “Suffering was what united the varied hearts of all these people and brought them resurrection.”

The Long Bridge is a wonderful book, much more than another retelling of the horrors of the gulag. It is, of course, a historical document, but it is also a psychological study, a development of a philosophy, and an inspiration. I recommend it highly.

Urszula Muskus died in her sleep, one page still left in the typewriter, the chapters neatly laid out on the floor of her room. Although family and friends funded a small printing of the Polish original to be distributed among the Polish community in London plus a few copies for family in Poland (where any discussion of this topic at that time could lead to arrest), it was Peter Muskus who was determined to have it published in English. He saw to the translation, contacted organizations such as Katyń Families and the Memorial Society of Russia, consulted Kazakh journalists and an American professor, hired English editors and spent years looking for a publisher. He finally engaged professional evaluators and then, armed with enthusiastic endorsements, approached over 20 publishers who showed some interest only to reject it in the end. Finally, a chance meeting with the director of Sandstone Press in 2009 enabled him to present his grandmother’s book one more time, this time enthusiastically accepted.

To read more about the Muskus family and view some wonderful old photographs, check out Peter’s website. And while you’re there, take a look at the home page. You may find it very tempting indeed to take a trip to Scotland and meet Urszula Muskus’ grandson.

CR

Pingback: Kaia, Heroine of the 1944 Warsaw Rising

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption