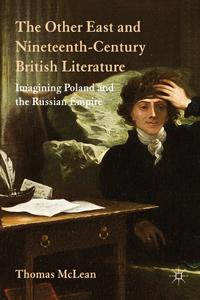

The Other East and Nineteenth-Century British Literature: Imagining Poland and the Russian Empire

The Other East and Nineteenth-Century British Literature: Imagining Poland and the Russian Empire

By Thomas McLean

Palgrave Macmillan 2012

Thomas McLean’s The Other East and Nineteenth-Century British Literature: Imagining Poland and the Russian Empire presents an engaging history of the emergence and evanescence of cultural representations of Eastern Europe and its people. This includes historical figures, such as Catherine II of Russia and Tadeusz Kościuszko, as well as fictional characters that derive from these figures, such as Jane Porter’s sympathetic portrait of a Polish exile, Thaddeus Sobieski or George Eliot’s Will Ladislaw. McLean’s goal is to analyze these representations – still rather neglected in research – and to look at how they reflect on nineteenth-century Britain and its changing political climate. It is a fascinating project that could potentially pose some significant challenges, yet I am pleased to say that McLean handles it exceptionally well.

McLean’s narrative is chronological and starts with the partitions of Poland at the end of the eighteenth century. Catherine II emerges as the anti-hero of the first chapter. McLean argues that the partition of Poland not only served as evidence of the Russian empress’s imperial ambitions, but also acted as an uncomfortable reminder of Britain’s own aggressive colonial politics. For the British public, the figure of Catherine the Great came to be associated with unconstitutional despotism and an insatiable geopolitical appetite (captured by such epithets as “the Russian harpy”). This negative image was also steeped in misogynist fears of a dominating female trumping over effeminate masculine figures of kings, princes and generals. By analyzing this cultural representation of Catherine in British culture in the context of Poland’s partitions – most notably, William Blake’s cryptic 1794 poem Europe: A Prophecy – McLean effectively sketches an outline of the “imaginary geography” of Eastern Europe, which will continue to generate cultural representations of East-European nations (mainly Poland and Russia), as well as their idealized representatives in British literature throughout the nineteenth century.

If the British reaction to Poland’s partitions unambiguously painted Catherine as a political villain, history soon provided the British public with a positive hero in the figure of Tadeusz Kościuszko, a veteran of the American Revolution and the general of the failed Polish insurrection against Russia. McLean analyses the process of the “romanticization” of the Polish hero by Coleridge, Campbell, and other British poets and then clashes these representations with the image that the scarred and exiled Kościuszko presented to his admirers during a short stay in London and Bristol in 1797: an image most famously captured by Benjamin West, whose intimate and vulnerable portrait of the Polish general adorns the cover of McLean’s book. This representation of Kościuszko is a complex one, soliciting sympathy and sorrow among the British public at the tragic fate of a defeated nation, but also justifying political inaction towards Poland and making Kościuszko and his homeland “familiar symbols of exile, suffering, and defeat.”

The domesticated and effeminate image of the fallen hero Kościuszko, combining both romanticism and sentimentality, gave birth to a number of literary figures of Polish exiles, which are the subject of McLean’s next three chapters. In my opinion, these three chapters constitute the most insightful and the best-argued portion of the book; its conceptual core, so to speak. The most prominent of these early representations is that of Jane Porter’s widely popular historical romance-novel Thaddeus of Warsaw. Porter’s Thaddeus Sobieski, clearly modeled on Kościuszko, is a veteran of the failed insurrection of 1794. After suffering defeat and having lost his homeland, he arrives to London, deprived – like typical heroines of British novels – of wealth, stature, and other attributes of social position. Despite his hapless situation, he manages to get by and successfully settle in Britain. His gallantry and magnanimity also effect a positive change in the lives of many Londoners. Like West’s Kościuszko, Porter’s idealized figure of a Polish expatriate is ambiguous: although presented as an irresistibly attractive character, Thaddeus eventually abandons dreams of his homeland and assimilates into British society, thus underscoring the hopelessness of Polish struggles for independence.

Lord Byron’s Mazeppa, published already after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, offers a slightly different look at the Polish nation. McLean situates the poem – and its character – in the context of the Vienna Congress. It was an event that once again brought the issue of Poland to the attention of British intellectuals and artists, most prominent among those being Leigh Hunt, John Keats, Walter Savage Landor, and Lord Byron. The latter’s Mazeppa is a very different narrative from Porter’s Thaddeus of Warsaw. Mazeppa is not a gallant yet powerless character, like that of Porter’s novel. While his narrative about the struggle between Charles XII and Peter the Great closely parallels that of Napoleon’s fateful Russian campaign, his own story of successful revenge delivers a strong message: “not to beg before a king or tsar, but to remember the past, to await a time when personal resolve and good fortune allow even a peasant – or, like Kościuszko and Mazeppa, a minor noble in peasant’s dress – to confound a lord whose punishment does not fit the crime…” Byron’s poem introduces some new and interesting tropes that British culture could associate with the Polish national cause, although – for better or worse – it did not have the same effect on the British imagination as Porter’s tale of a dispossessed hero.

The period between 1830 and 1849 witnessed a change in Britain’s attitude towards Polish struggles for independence: from feelings of sympathy and renewed interest after the unsuccessful Russo-Polish war of 1831 to a more problematic, class-conscious affinity to, finally, less interest in, and exhaustion by, the subject. Chapter 5 of McLean’s study traces the polar shift that occurred in the public interest of Britons by looking at a plethora of cultural texts produced in the so-called late Romantic period. By tracing these developments, owing as much to the existing tradition of Polish characters and tropes in British literature as to the current situation, McLean creates a historical bridge that connects the Romantic and Victorian periods and their respective attitudes towards Poles and Poland.

In Chapter 6, McLean introduces another Eastern “other” to the picture, Circassia and the Circassians. The interest in Caucasian ethnic groups in Britain coincided with an interest in the Russo-Circassian War in the 1830s and 40s. Much like the image of “gallant and magnanimous” Poles, the imaginary representation of a “fair Circassian” (a version of Rousseau’s noble savage) was created in equal parts from stark opposition to Russia’s greedy imperialism and the British public’s fascination with the “oriental.” McLean shows that just as in the case of Poland, the Circassian stereotype that began to appear in British culture also wavered between eliciting sympathy and interest on the one hand, and evoking dangerous comparisons with Britain’s own problematic relationship with Ireland on the other.

In the final full chapter of the study, McLean focuses on the Victorian image of Poles by closely examining the figure of Will Ladislaw, a character in George Eliot’s Middlemarch. With his ancestry veiled in mystery – both fictional and textual – Will is indicative of the ambiguous stance of Victorian culture towards the figure of a Polish exile. Although the core of Eliot’s model for Will is the Romantic image modeled on Kościuszko (and Porter’s Thaddeus), he also displays some of the less than positive tropes of a radical reformer and conniving voluptuary, both being characteristically Victorian developments. Will’s marriage to Dorothea at the end of Middlemarch makes him a “thread to the future,” heralding a more open type of world, and hence an ultimately positive character. Thanks to this last development McLean’s study ends on a positive note, followed by a brief coda on Joseph Conrad’s minor engagement with the stereotype of the Polish exile (in two short stories, “Amy Foster” and “Prince Roman”).

Overall, Thomas McLean’s book is a well-researched and elegantly written study that can appeal to the non-specialist as well as to fellow scholars. It offers an extremely interesting account of the evolving image of Poles and Poland in nineteenth-century British culture, one that reflects the turbulent history of both nations. McLean seemingly effortlessly weaves together biographical anecdotes, historical facts and close readings of a variety of literary and non-literary texts, raising many interesting points along the way (many of which I had to omit in this review). His purpose is always clearly stated in each chapter and section, which makes his arguments lucid and easy to follow. One of the few criticisms I have of this book is that it does not offer a window into the future in the form of a chapter (or section) outlining further developments of the imaginary representation of Eastern Europe in twentieth-century British culture. A brief analysis of Joseph Conrad’s stories cuts off McLean’s narrative without giving a proper conclusion to his study. Also, despite the inclusion of two chapters on Catherine II and Circassians, the study focuses almost exclusively on Poland and the image of the Polish exile, which may disappoint those who expect a more comprehensive treatment of Eastern Europe in British culture. However, neither of these shortcomings can overshadow the overall positive impression this excellent study leaves on the reader. I can only hope that the several projects McLean initiates in this book will find their continuation in Anglo-American as well as Polish scholarship. CR

CR note: For more information about the cover painting of Kosciuszko by Benjamin West visit the website of the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College.