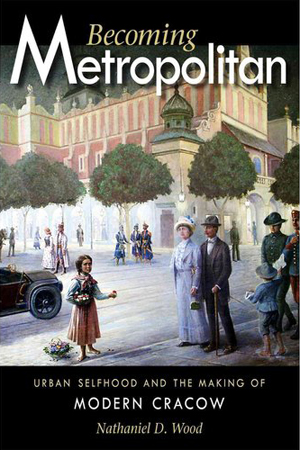

Becoming Metropolitan: Urban Selfhood and the Making of Modern Cracow

Becoming Metropolitan: Urban Selfhood and the Making of Modern Cracow

By Nathaniel D. Wood

Northern Illinois University Press, DeKalb, IL, 268 pages

Kraków’s historical and cultural significance in Poland – and in particular its role in the national movement while Poland was under partition – is something that is widely recognized. However, in Becoming Metropolitan: Urban Selfhood and the Making of Modern Cracow, Nathaniel Wood challenges the idea that national themes and Habsburg politics were the only primary forces at play in early twentieth century Kraków. Instead, the work aims to broaden this narrow historiographical scope by making the case that processes of modernization during the period were creating an urban and cosmopolitan identity among the inhabitants of a previously sleepy provincial town. This urban self-hood, Wood argues, both coexisted and at times superseded national identity as the city began transforming itself into a modern European metropolis akin to its Western counterparts.

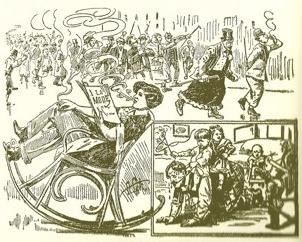

Cartoon showing the horrors of a modern woman (wearing pants!), in Kurier Codzienny, March 29, 1912.

“World Flipped upside Down. A Picture from the near Future”

Instead of concentrating on the elite and the more familiar literature (often preoccupied with bucolic and national themes) of authors strongly associated with Kraków such as Stanisław Wyspiański and Lucjan Rydel, Wood justifies his use of diaries, archives, and especially the press as source material to reflect a broader range of society. His primary evidence is the popular press (namely Kuryerek Krakowski, Nowiny dla Wszystkich and Ilustrowany Kurier Codzienny) which began to emerge in Kraków in the early 1900s. He chronicles its beginnings while accentuating its uniqueness as a source that both illustrated reality and concurrently managed to shape it. He explains that the boulevard press influenced its audience by making readers feel part of a metropolitan “imagined community”. This was accomplished through various articles that actively promoted plans to create a Greater Kraków by incorporating the surrounding suburban communities, or the frequent allusions and comparisons made between Kraków and major European cities that could be a source for emulation and familiarization with urban life.

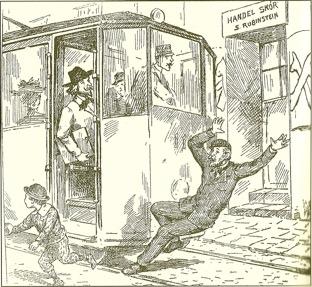

Mr. Żabner’s Ill-timed Dash. Kuryer Krakowski, April 2, 1903, on the danger posed by trams speeding at 8 mph.

Wood manages to carefully recreate Kraków for the reader much as it would have appeared to a newcomer at the turn of the century, constructing a detailed historical backdrop by describing the neighbourhoods, living conditions, politics, as well as the professional, social and ethnic groups that made up the city. He points out that the average newcomer in all likelihood would have been a young peasant girl searching for the monument of one of Poland’s greatest poets, Adam Mickiewicz. At the time, the statue of the revered national hero was primarily associated as the place to find work as a domestic servant. Wood uses this example to neatly illustrate the discrepancy between the intended historical importance meant for the monument in a city that cherished and promoted its national heritage and how it was seen in the public sphere on a functional level. He further elaborates that the use of national rhetoric and references to Kraków’s historical past made by reforming politicians were generally linguistic flourishes that helped to justify the city’s need for modernization and stemmed from more practical local concerns.

Especially intriguing are the two final chapters which deal with shifting attitudes toward technology and adaptation to city life. They also provide curious insight into the exploitative, moralizing and voyeuristic nature of the press. In a chapter entitled “Big City Muck” Wood reveals how sanitary conditions, crime, corruption and the decadent nightlife associated with a big city were presented in the so-called “gutter press” and how both these positive and negative aspects of living in an urban environment brought city dwellers closer in identifying with other European cities. Overall, Becoming Metropolitan is interspersed with fascinating (and at times very amusing) excerpts, pictures, and caricatures from the popular press. The visual material also includes photographs of Kraków and portrays the changing look of its varied inhabitants amid this period of transformation.

Trams on the Main Square in Krakow.

Photograph from the 1920’s.

It is crucial to note, however, that the author does not attempt to undermine the important role that the city which hosted Józef Piłsudski’s Riflemen had to play in the national revival of Polish culture and the re-establishment of its nationhood. Instead, Nathaniel Wood presents the complicated interaction between the past and processes of modernization that has largely been omitted in scholarship, accentuating that various factors contributed to the layers of personal identification that existed among the inhabitants of Kraków. While industrialization and the creation of the modern nation-state undoubtedly played a huge role in the development of national consciousness among the masses, he convincingly argues that urbanization also created a cosmopolitan identity which could often be more relevant to the average Krakovian on a day to day basis. Wood’s work manages to open a new discourse by confronting many popular assumptions regarding the preeminence of the national question that can relegate complex forces to the one-dimensional. Becoming Metropolitan is an engaging read that highlights that Kraków’s inhabitants likewise had a desire for their city to join into what they thought it meant to be part of European Civilization. In light of Poland’s accession to the EU and the desire of many Poles to catch up to the West and assert their European identity, it is tempting to muse on how many of these themes and attitudes would have been similarly relevant to their historical counterparts over a century ago.

CR

Your style is so unique compared to other folks I’ve read stuff from.

Many thanks for posting when you’ve got the opportunity, Guess I’ll just

book mark this site.