The photo was unmistakably me, in Nehru shirt and bell bottoms, a cigarette dangling rakishly in my right hand… on the front page of Czechoslovakia’s Socialist Union of Youth newspaper. Of course it was all a misunderstanding – but nothing was easy to explain back then.

My father thrust the simple, handwritten note at me from across the dinner table. “Is this your son?” it read.

The note was signed by an engineer, a Czech emigré, stationed at one of Ontario Hydro’s more remote outposts, and it was stapled to a grainy photocopy of a front page article from Mlada fronta, the organ of Czechoslovakia’s Socialist Union of Youth. The photo was unmistakably me, in Nehru shirt and bell bottoms, a cigarette dangling rakishly in my right hand. The summer before, I had managed a work camp of international youth volunteers one of whom had been a Czech journalist. Naively, I had consented to be interviewed about conditions facing youth in the West. I had told him what was common knowledge to any young North American in the late 1970s – that in the wake of the first oil crisis and a U.S. recession, the party we’d all been promised in the 1960s was coming to an end and, for the first time since WWII, university students were being told not to expect jobs when they graduated. I thought I’d simply been stating the obvious, but it was an act of betrayal in the eyes of the Czech engineer, who had recognized my father’s surname and sent him the article after tracking him down at Hydro’s head office in Toronto.

My Dad said nothing, but the steely reproof in his eyes made the message clear: in this world, you don’t stick your neck out, you keep your opinions – and your stories – to yourself.

He knew, along with many in Toronto’s Polish diaspora, what happened to those who did otherwise. He had shown me the photos in his album of schoolmates from his days at teacher’s college in Lwów before the war, pointing out which ones had been shot by the Nazis, and which ones had been arrested by the Soviets never to be seen again – the writers, the thinkers, the ones who spoke out. Like everyone in Toronto’s Polonia, he rejoiced in the freedoms of the West, but he knew from experience how fragile those freedoms could be. You never knew who might be reading or watching, and the engineer’s letter was a case in point.

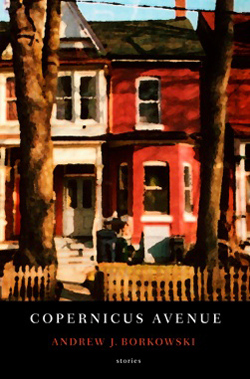

More than three decades later, as I promote my new collection of short stories about the post-war Polish-Canadian experience at readings and festivals, I’ve learned how new the Polish narrative is to the Canadian mainstream. Non-Polish Canadians are surprised to learn about Soviet complicity in the partition of 1939 that started WWII, about the mass murders and deportations that claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands, or to learn that a million non-Jewish Poles fell victim to Nazi death squads, forced labour and concentration camps alongside three million of their Jewish compatriots, while another million gentile Polish civilians died as result of planned starvation and other hardships or as collateral damage.* Polish participation in key Allied battles such as Monte Cassino and the Battle of Britain, and (alongside Canadian troops) in Normandy and Holland is also news to many of my readers.

More than three decades later, as I promote my new collection of short stories about the post-war Polish-Canadian experience at readings and festivals, I’ve learned how new the Polish narrative is to the Canadian mainstream. Non-Polish Canadians are surprised to learn about Soviet complicity in the partition of 1939 that started WWII, about the mass murders and deportations that claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands, or to learn that a million non-Jewish Poles fell victim to Nazi death squads, forced labour and concentration camps alongside three million of their Jewish compatriots, while another million gentile Polish civilians died as result of planned starvation and other hardships or as collateral damage.* Polish participation in key Allied battles such as Monte Cassino and the Battle of Britain, and (alongside Canadian troops) in Normandy and Holland is also news to many of my readers.

“Why didn’t we know, until now?” interviewers ask me. “Where have you (meaning writers of post-war Polonia’s second generation) been all this time?”

I’ve been writing fiction since my mid-twenties and, for the first fifteen years my Polish background was the last thing I wanted to write about. Too complicated. Too fraught. Too sensitive. Too many Poles of my father’s generation figuratively standing over my shoulder, distrustful of the creative process and rumbling “That’s not how it really was!” These weren’t my stories to tell, and there was always the spectre of the Czech engineer or his Polish equivalent, ready to pounce in judgement. I was lucky to know more of my family’s story than many of my generation whose parents took theirs to the grave – but these were their stories, and they themselves had been very selective when it came to passing them on to their children.

Today, when authors representing “newer” immigrant groups – from South Asia, China, Africa, and the Caribbean – regularly appear on the shortlists for major prizes, it may seem strange to some that writers from a group as large and historic as Polish-Canadians haven’t done the same. But anyone under forty needs to be reminded that the Canada Polish veterans came to in the late 1940s was very different from the Canada that later arrivals came to in the 1970s and beyond. The, psychotherapeutic revolution and the confessional ethos of “Oprah culture” were still decades away. Few groups in Canada’s refugee-rich history had arrived with so vast a packet of horrors on their backs, and the best way to survive was to forget.

The Canadian cultural mainstream was a far less welcoming place in the post-war world. Literature was the preserve of the (usually privileged) Anglo-Canadian majority. What writers there were seemed to be hugely underappreciated. Outside of Don Messer’s Jubilee and Hockey Night In Canada, English Canadians seemed hugely uninterested in their own cultural products. In such a climate, why would Polish immigrants, intent on seeing their children rebuild family fortunes shattered by the war, encourage their children to enter a field that the mainstream itself held in such little regard?

The wave of progressive nationalism that propelled English Canada into the 1970s changed that, but Canlit remained a largely unaccented affair. Official multiculturalism was born in that decade (arguably in Toronto’s Polish community – the first Minister of State for Multiculturalism being the community’s MP, Dr. [later Senator] Stanley Haidasz) but, although the absolute right course for Canadian social policy, it was a creature of politics and while it fostered much in the way of dance troupes, folk art and the erection of the occasional monument, it did little to inject a literary presence into the mainstream until the1980s. By that time, Polonia’s baby boom generation were well on their way to careers as teachers, doctors, mechanics, nurses, and engineers. Culture, in the community I grew up in, was largely an adornment, or at best a way of making you a more effective lawyer or architect.

Those of us who did venture into the cultural arena were, by-and-large, only too willing to soft-peddle our Polish roots. Even as Italian Canadians (Nino Ricci), Chinese Canadians (Wayson Choy) and Japanese Canadians (Joy Kogawa) made their contributions to the literary mosaic, we maintained our silence. Why? Perhaps it was because we knew that, in the post-Vietnam era of detente, the peace movement and the anti-nuclear campaigns, the Polish story contained a few too many thorny and inconvenient truths. How to write about the fallout of Katyn and the deportations, without playing into the hands of hawkish cold warriors? How to explain Polish romantic nationalism in dispassionate, comfortable North America? How to articulate the deep links between moral forces – Polish Catholicism and the spirit of resistance – that seemed antithetical to one another on this side of the Iron Curtain? Best to put it all behind us, be cool, fit in.

These conundrums are no less difficult to pick apart now than they were twenty years ago. But two things have changed. First, the Iron Curtain has finally fallen under its own weight. In Poland, Poles themselves can re-examine their own history untrammeled by the distortions and dissimulations of the Soviet regime. Here in Canada, we are free to tell our story without the risk of tumbling into the crevasse that opened up when the world was torn in two in September 1939.

Second, the war generation is fast disappearing and we’ve realized, hopefully not too late, that their story is the most precious thing they leave us. It can be terrible at times, and not as simple as some might have thought or wanted it to be. But it’s a magnificent story – one of the power and resilience of the human spirit – and it’s time we shared it.

CR

*These figures are drawn from Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, by Timothy Snyder, Basic Books.

Pingback: Nowhere Places: Mining the Polish Experience