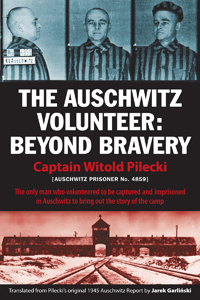

The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery: Captain Witold Pilecki

The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery: Captain Witold Pilecki

By Witold Pilecki

Translated by Jarek Garlinski

Introduction: Norman Davies, FBA

Foreword: Rabbi Michael Schudrich, Chief Rabbi of Poland

Aquila Polonica Publishing, April 30, 2012, 460 pages

His number in Auschwitz was 4859. The two thirteens—comprised by the addition of the inner and outer digits—he considered lucky even though his companions perceived them as an omen of impending death. Luck certainly helped him survive the two-and-a-half-year ordeal in one of the Reich’s most infamous concentration camps. But equally important was his willpower, courage and ingenuity.

Witold Pilecki with wife Maria i son Andrzej, Ostrów Mazowiecka, 1933 r., via Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance

At the outbreak of the Second World War in September of 1939, when German and Soviet forces steamrolled into Poland, Witold Pilecki was a 38-year old reserve second lieutenant in the cavalry. As his homeland was partitioned once again between the two neighbours, he quickly joined the growing military resistance organization, which would eventually evolve to become commonly known as the Home Army (Armia Krajowa, AK). Within a year, this father of two volunteered for an unusual mission that would test the physical and psychological limits of even the toughest of men. In September of 1940, he intentionally walked into a roundup in order to be sent to Auschwitz—a camp about which the Polish underground had heard but knew little. Rather than relying on rumour, they wanted to get accurate and reliable reports by one of their own. Within days, Pilecki “bade farewell to everything [he] had hitherto known on this earth and entered something seemingly no longer of it.”

A record of his hardships in what he describes as the “great mortuary of the half-living,” a stay that lasted for nearly a 1000 days, has now been superbly translated and published in The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery. This is the third report that Pilecki wrote in the summer of 1945, while in Italy. Two shorter accounts were written earlier: one immediately after his escape from the camp in June of 1943, and the other in autumn of the same year. But it is this final testimony that offers the most comprehensive tale of his experiences.

Writing for his military superiors, he was ordered to “stick to dry facts,” aiming to quickly produce an accurate summary, and not a literary masterpiece. He complains of being rushed and not having enough time to say everything. So many fallen comrades, so much human destruction, so many important images, so much bravery that needs to be conveyed. As hard as Pilecki tries to stick to the hard facts, at one point, he pauses and admits that the story “comes from within [him] and perhaps that is why it’s not so dry.” The end result is an important historical document that will join other first-hand accounts of life in concentration camps such as those of Tadeusz Borowski or Stanisław Grzesiuk. The rich narrative of courage and survival offers many interesting and powerful images. Only a handful can be recounted here.

One of the most evocative themes is the chronicle of the camp’s evolution from 1940 to 1943. Anyone walking through the gates of Auschwitz quickly realized that the aim of the SS was not only to break all the inmates psychologically, but to end their existence in violent and cruel ways. By the war’s end, the death camp claimed 1.5 million lives. In the early period, the killing was done using the most brutal methods. Those shot at the “wall of tears” seemed to be the lucky ones for others died in much slower and more painful ways, such as through exhausting physical exercise, the “circle of death.” As Pilecki relates, the first victims of these punishments were Polish political prisoners. But by 1941, there were changes introduced in the camp, and with the launching of Operation Barbarossa, Soviet POWs became the main prey of the “huge mill” that turned “living people into ashes.” Eventually, the Poles and the Soviets would have to make room for an even more radical goal embodied in the Final Solution. “There was a change in the murder methods,” Pilecki sarcastically notes as trains of Jews from across Europe arrived, “to more civilized ones…by which thousands were killed daily by gas and phenol.”

The narrative also provides insight about Pilecki’s ingenuity in creating an underground resistance movement within the camp. At the very beginning, he confidently asserts the fourfold objective of his mission: to boost morale amongst the inmates; to organize resources for survival; to send reports to his superiors; and to prepare for an uprising. His first report was sent already in November of 1940, and several others followed. Through inspiration and courage, he quickly recruited people into an underground organization, eventually even creating platoons that were ready to erupt against their tormentors at a moment’s notice. To Pilecki’s bitter disappointment, which he does not hide from his superiors, the order for an uprising is never issued.

Equally fascinating is his ability to inspire cooperation amongst men from different walks of life and political stripes. Pilecki admits that all who lived in the camp changed. Auschwitz created an environment where one could easily “slither into a moral swamp.” Yet, it was also a place where “a man was seen and valued for what he really was,” where, as Pilecki explains, “we had all become just our bare essence.” Many of the storylines are about how friendships borne in shared suffering, work assignments, and ingenuity helped people cope and survive. They are about the intricate maze of gathering and managing resources and lucrative positions throughout the camp. This was a dangerous game in which the stakes were of the highest calibre—one’s life.

Finally, the report is a story of a personal struggle in the face of extreme circumstances. Pilecki asserts that “the hardest thing of all is to write about oneself.” Nevertheless, much of the writing reveals a personal journey. There is an inner struggle to avoid “becoming someone else.” In moments of crisis, he finds solace in his faith and patriotism. Acutely aware of changing—of becoming insensitive when surrounded by so many corpses, he wants to remember all his fallen companions. “To be honest,” he admits after learning of the death of a friend, “can I write that someone was ‘much-missed’? I missed them all.”

Although there is little reflection on the scale of the atrocities, Pilecki cannot resist the juxtaposition of the camp’s hellish reality with the world outside. At several intervals, he asks: “Was there still a world outside where people lived normal lives?” Even by the war’s end, he still laments over the world’s indifference to the unrelenting spilling of blood. Given the mass murder at Auschwitz, he questions humanity’s advancement: “can we from the 20th century look our ancestors in the eye and…laughably…prove that we have attained a higher cultural plane?”

In April of 1943, Pilecki escaped from Auschwitz. He participated in the Warsaw Uprising in the following summer after which he was captured and became a German prisoner-of-war. He was released at war’s end. But the world of 1945 was much different than the world of 1939. Although the Allies had won the war, Poland had lost the peace. Falling behind the emerging Iron Curtain, it was destined for Sovietization.

Once again, Pilecki was recruited for intelligence work, but this time on the Soviet occupants. He collected information about Soviet atrocities against the former soldiers of the AK. Even after his cover had been blown, he refused to leave. Arrest and torture did not break his spirit as he refused to admit to acts of espionage and fabricated assassination attempts. Nonetheless, he was found guilty and executed in 1948 as an imperialist spy. Thereafter, a blanket of silence fell over his wartime acts of bravery. It was not until the collapse of Communism across Eastern Europe that his name and deeds were rehabilitated.

There is no doubt that Pilecki wrote the report for his commanding officers. But he also left a record for future generations. At one point he asks that “people living comfortably in the outside world”—much the same could be said of us in the present—“make a minimal effort to read these pages and focus a few times on a single image.” Many such images of unspeakable suffering and unassuming courage spill across the pages of The Auschwitz Volunteer.

CR

The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery: Captain Witold Pilecki is the winner of the 2012 PROSE Award for Biography and Autobiography from the Association of American Publishers.

Pingback: The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery: Captain Witold Pilecki

Pingback: Krystyna Wituska: Her Life and Literary Afterlife

Pingback: 2014: The Year of Anniversaries

Pingback: Bulletin Board Summer 2015

Pingback: Poland As An Ally: WWII Photo Essay

Pingback: Welcome to Winter 2016!

Pingback: The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery – Technologie XDZ