Poland’s magnificent, 10-million strong opposition movement to communism, Solidarity, was not only successful, but it was peaceful. No matter the provocation, Solidarity never resorted to violence. When it achieved victory, it remained true to its commitment to peace. There were no reprisals, no show trials, no riots; some hated monuments were removed but there was no vandalism. A formula was worked out for an initial sharing of power until the hated communists were soundly defeated in a legitimate election.

Poland’s magnificent, 10-million strong opposition movement to communism, Solidarity, was not only successful, but it was peaceful. No matter the provocation, Solidarity never resorted to violence. When it achieved victory, it remained true to its commitment to peace. There were no reprisals, no show trials, no riots; some hated monuments were removed but there was no vandalism. A formula was worked out for an initial sharing of power until the hated communists were soundly defeated in a legitimate election.

It was an awe-inspiring show of discipline and moral strength.

But what about justice?

The first post-Communist Prime Minister, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, declared that it was time to draw a thick line between the past and the present, that the country must live in the present and look to the future, and not dwell on the past.

And so the years passed, and the crimes of the past remained unacknowledged. Perhaps this contributed to the peaceful transition, prevented a rush to judgment or a summary settling of scores. Besides, there was much to do at a practical level to restore a civil society and an economic system that had been destroyed by communist rule. Many older people wanted to forget, and the young didn’t want to hear about it. Or so it seemed.

But a thick black line separating the past from the present did not erase the past. The crimes that were committed remained an open wound; the victims continued to feel the pain, the guilty remained guilty. And the country could not live without its history. Those who remembered still craved justice while the young, for their part, began to show a much greater interest than expected.

In a February 21 article in the New York Times, Poland Leads Wave of Communist-Era Reckoning, a Polish author of a bestselling novel about the secret police, Tadeusz Miloszewski, put it this way: “I have a feeling since this time wasn’t explained at all, the foundations of my country are fractured.”

The repair of these foundations has been addressed, but far too slowly. For victims, the accounting is too long in coming and for many, in fact, too late. Still, with a disciplined approach not unlike that of Solidarity, the truth is being exposed. The country’s Institute of National Remembrance, with its ongoing investigations of crimes committed by both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia – as well as by the post-war Polish communists who ruled Poland on behalf of Russia, works with leading historians and has published hundreds of books, conducts symposia, and assists in producing educational materials.

At another level, reaching a far larger number of people, books films and television programs have also begun to explore the subject, often with thoughtful and sensitive presentations. These include major productions such as Wajda’s Katyń, and also more modest films, such as The Death of Captain Pilecki. It is this film – made on a modest budget and not eligible for film festivals since it was originally made for television – that we are reviewing in CR this issue.

The Death of Captain Pilecki

“Fear was our constant companion. It never left us. It was not a matter of escaping fear, but of mastering it.”

Aleksander Gieysztor, speaking of his time during the German occupation when he was a member of the Polish Home Army and also of Żegota.

I was reminded of this statement by Aleksander Gieysztor as I watched the Polish actor, Marek Probosz, in the role of Witold Pilecki in the 2005 film about a communist-era show trial and one of the great post-war miscarriages of justice. Probosz had a very difficult role to play, that of a heroic man who maintained complete mastery of his soul in the face of unspeakable torture.

I was also reminded of a story I heard from a woman I met in Poland who, together with her two children, survived the war living in a shed after she had been dispossessed, her husband’s whereabouts unknown. Terror stricken by every encounter with German soldiers, she was unable to look after her children properly. Added to her hunger and fear was shame, because it was her 10-year old daughter who had to fend for them and find food. Until one day when she had what she described as a religious experience: “I gave my life to God and at that moment I lost my fear. I am not a stupid woman. I knew the Germans could still beat me or kill me. But they couldn’t have me. It was a feeling that never left me and served me well after the war too. The communists couldn’t have me either.”

While there was no indication in the story of Witold Pilecki that he had undergone a spiritual experience, he had clearly mastered his fear, so much so that no matter what his body was subjected to, his inner being was beyond the reach of his brutish tormentors. As portrayed by Probosz, Pilecki was a man of immense dignity, a man who personified truth and honor.

It was a role that could easily have been played with heavy-handed drama, or with overdone stoicism. Probosz successfully avoided both. His Pilecki was a man of both reason and passion, of sensitivity and steadfastness.

The Death of Captain Pilecki tells the story of a Polish officer who, during the German occupation, volunteered to be arrested and sent to Auschwitz in order to get first hand information about this terrifying prison camp. He was prisoner number 4859, of an eventual 150,000 Polish prisoners.

His assignment was to gather intelligence, organize a cell of resistance, smuggle out his messages, and eventually to lead a mass breakout. He managed the first three but not the last, though he eventually did escape himself. The information he passed on to his Polish commanders who in turn passed it on to the Allies, was never fully believed in the West.

After his escape, Pilecki continued to serve in the Home Army and fought in the uprising of 1944, ending the war in a German POW camp. After his liberation, he returned to Poland, this time accepting an assignment to gather intelligence on the conditions imposed by the Soviet regime. Arrested by the Secret Police, he was tortured, tried in a show trial, and sentenced to death. He betrayed no one, admitting that he was sending information about the economic and political situation in Poland, but denied engaging in any illegal activities.

Executed in May 1948, he was buried in secrecy, the location of his grave unknown to this day. The communist authorities also banned any mention of his name, a ban that remained in force until 1989.

Until this 2006 production of The Death of Captain Pilecki, written and directed by Ryszard Bugajski, millions of Poles had never heard of the heroic officer who had endured so much in his fight against Nazi Germany, only to be branded a “fascist” by Hitler’s partner in crime.

The film is a faithful recreation of his trial, based on the documents that had for so long been kept secret. In Poland the film was a revelation, watched by millions, while in the United States it has had regular screening every year since 2007 though with very limited distribution. While it is a tense drama and a powerful story in its own right, the film is of special interest to anyone studying totalitarian regimes, human rights abuses, and also the indomitable will to be free.

The English subtitles are well done though some historical background would be helpful for people not familiar with it. The Death of Captain Pilecki illuminates an important chapter in Poland’s post-war history, a chapter virtually unknown outside of Poland. While the Soviet system censored this history, western historians and journalists have no excuse for being ignorant of it. It was merely convenient to omit references to the West’s betrayal of a faithful ally.

British historian Michael R.D. Foot noted that, “The Foreign Office’s betrayal of Poland is the darkest chapter in its history, even if that betrayal was a strategic necessity.”

Students of brutal dictatorships and their relationships with Great Powers should keep Professor Foot’s statement in mind during their discussions and consider whether it is, perhaps, a bit self-serving? “Strategic necessity” is often not much more than a euphemism for the exercise of power – cynical, cruel, and motivated by greed.

CR

Imagery:

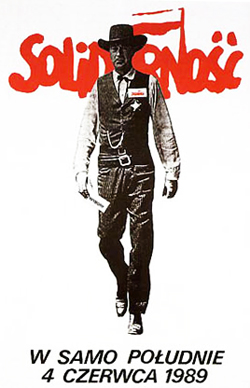

- The poster combines Solidarity’s iconic logo with another iconic American image: Gary Cooper striding down the street in “High Noon.” The poster was used in 1989 throughout Poland to encourage Poles to vote; instead of a gun, Mr. Cooper carries a ballot.

- Marek Probosz as Cavalry Captain Witold Pilecki in The Death of Captain Pilecki.

Irene Tomaszewski is a writer and editor of CR. She is the co-author, with Tecia Werbowski, of "Codename Żegota: The Most Dangerous Conspiracy in Occupied Europe," published by Praeger in 2010, and translator /editor of "Inside a Gestapo Prison: The Letters of Krystyna Wituska" published by Wayne State University Press in 2005.

The Death of Captain Pilecki and Dealing with the Communist Past

Posted by Irene Tomaszewski on April 22, 2012 at 9:00 amIt was an awe-inspiring show of discipline and moral strength.

But what about justice?

The first post-Communist Prime Minister, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, declared that it was time to draw a thick line between the past and the present, that the country must live in the present and look to the future, and not dwell on the past.

And so the years passed, and the crimes of the past remained unacknowledged. Perhaps this contributed to the peaceful transition, prevented a rush to judgment or a summary settling of scores. Besides, there was much to do at a practical level to restore a civil society and an economic system that had been destroyed by communist rule. Many older people wanted to forget, and the young didn’t want to hear about it. Or so it seemed.

But a thick black line separating the past from the present did not erase the past. The crimes that were committed remained an open wound; the victims continued to feel the pain, the guilty remained guilty. And the country could not live without its history. Those who remembered still craved justice while the young, for their part, began to show a much greater interest than expected.

In a February 21 article in the New York Times, Poland Leads Wave of Communist-Era Reckoning, a Polish author of a bestselling novel about the secret police, Tadeusz Miloszewski, put it this way: “I have a feeling since this time wasn’t explained at all, the foundations of my country are fractured.”

The repair of these foundations has been addressed, but far too slowly. For victims, the accounting is too long in coming and for many, in fact, too late. Still, with a disciplined approach not unlike that of Solidarity, the truth is being exposed. The country’s Institute of National Remembrance, with its ongoing investigations of crimes committed by both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia – as well as by the post-war Polish communists who ruled Poland on behalf of Russia, works with leading historians and has published hundreds of books, conducts symposia, and assists in producing educational materials.

At another level, reaching a far larger number of people, books films and television programs have also begun to explore the subject, often with thoughtful and sensitive presentations. These include major productions such as Wajda’s Katyń, and also more modest films, such as The Death of Captain Pilecki. It is this film – made on a modest budget and not eligible for film festivals since it was originally made for television – that we are reviewing in CR this issue.

The Death of Captain Pilecki

“Fear was our constant companion. It never left us. It was not a matter of escaping fear, but of mastering it.”

Aleksander Gieysztor, speaking of his time during the German occupation when he was a member of the Polish Home Army and also of Żegota.

I was reminded of this statement by Aleksander Gieysztor as I watched the Polish actor, Marek Probosz, in the role of Witold Pilecki in the 2005 film about a communist-era show trial and one of the great post-war miscarriages of justice. Probosz had a very difficult role to play, that of a heroic man who maintained complete mastery of his soul in the face of unspeakable torture.

I was also reminded of a story I heard from a woman I met in Poland who, together with her two children, survived the war living in a shed after she had been dispossessed, her husband’s whereabouts unknown. Terror stricken by every encounter with German soldiers, she was unable to look after her children properly. Added to her hunger and fear was shame, because it was her 10-year old daughter who had to fend for them and find food. Until one day when she had what she described as a religious experience: “I gave my life to God and at that moment I lost my fear. I am not a stupid woman. I knew the Germans could still beat me or kill me. But they couldn’t have me. It was a feeling that never left me and served me well after the war too. The communists couldn’t have me either.”

While there was no indication in the story of Witold Pilecki that he had undergone a spiritual experience, he had clearly mastered his fear, so much so that no matter what his body was subjected to, his inner being was beyond the reach of his brutish tormentors. As portrayed by Probosz, Pilecki was a man of immense dignity, a man who personified truth and honor.

It was a role that could easily have been played with heavy-handed drama, or with overdone stoicism. Probosz successfully avoided both. His Pilecki was a man of both reason and passion, of sensitivity and steadfastness.

The Death of Captain Pilecki tells the story of a Polish officer who, during the German occupation, volunteered to be arrested and sent to Auschwitz in order to get first hand information about this terrifying prison camp. He was prisoner number 4859, of an eventual 150,000 Polish prisoners.

His assignment was to gather intelligence, organize a cell of resistance, smuggle out his messages, and eventually to lead a mass breakout. He managed the first three but not the last, though he eventually did escape himself. The information he passed on to his Polish commanders who in turn passed it on to the Allies, was never fully believed in the West.

After his escape, Pilecki continued to serve in the Home Army and fought in the uprising of 1944, ending the war in a German POW camp. After his liberation, he returned to Poland, this time accepting an assignment to gather intelligence on the conditions imposed by the Soviet regime. Arrested by the Secret Police, he was tortured, tried in a show trial, and sentenced to death. He betrayed no one, admitting that he was sending information about the economic and political situation in Poland, but denied engaging in any illegal activities.

Executed in May 1948, he was buried in secrecy, the location of his grave unknown to this day. The communist authorities also banned any mention of his name, a ban that remained in force until 1989.

Until this 2006 production of The Death of Captain Pilecki, written and directed by Ryszard Bugajski, millions of Poles had never heard of the heroic officer who had endured so much in his fight against Nazi Germany, only to be branded a “fascist” by Hitler’s partner in crime.

The film is a faithful recreation of his trial, based on the documents that had for so long been kept secret. In Poland the film was a revelation, watched by millions, while in the United States it has had regular screening every year since 2007 though with very limited distribution. While it is a tense drama and a powerful story in its own right, the film is of special interest to anyone studying totalitarian regimes, human rights abuses, and also the indomitable will to be free.

The English subtitles are well done though some historical background would be helpful for people not familiar with it. The Death of Captain Pilecki illuminates an important chapter in Poland’s post-war history, a chapter virtually unknown outside of Poland. While the Soviet system censored this history, western historians and journalists have no excuse for being ignorant of it. It was merely convenient to omit references to the West’s betrayal of a faithful ally.

British historian Michael R.D. Foot noted that, “The Foreign Office’s betrayal of Poland is the darkest chapter in its history, even if that betrayal was a strategic necessity.”

Students of brutal dictatorships and their relationships with Great Powers should keep Professor Foot’s statement in mind during their discussions and consider whether it is, perhaps, a bit self-serving? “Strategic necessity” is often not much more than a euphemism for the exercise of power – cynical, cruel, and motivated by greed.

CR

Imagery:

Related Posts: