*Young reader, if you wonder who those

folks were and how they got into my story, read on.

A very young Andrzej Derkowski in Poland with his parents

I am one of the 166,000 “Displaced Persons” from Europe who were admitted to Canada in the aftermath of World War II. However, I got here via a different route than most, involving a precarious but interesting ten-year journey through the Middle East and Africa. Also, I may have been the only one who came here on a work contract at the age of seventeen, alone and having no relatives or friends in this country.

On September 1st, 1939, I was awakened in Poland by the sound of air-raid sirens and bomb explosions. Adolf Hitler had resumed the Germans’ Drang nach Osten (push to the East), this time with his new blood-drinking buddy, Stalin. My father foresaw the horrors that were to follow and was lucky and resourceful enough to escape from Poland with me just ahead of the invaders.

Although I was only eight years old, some the darkest memories of that flight remain vivid. We crossed the border into Romania at night in a crowd of refugees on an unlit bridge, high above the white waters of a mountain river visible through gaps in incomplete decking. I realized that I was leaving my country, a happy life and a hopeful future, and entering into an unknown as dark as the night about us. I did not know till much later how lucky we were to have avoided the rule of either the Nazi Herrenvolk or of the butchers of Stalin’s N.K.V.D.

From Romania we got to Turkey, then to Palestine (then a British possession), and eventually, refugee camps in Northern Rhodesia and Tanganyika (now Zambia and Tanzania respectively). For my father it must have been an anxious and stressful journey, but for me, it was an educational one, a multi-year tour of exotic countries. We stayed in a wide variety of cheap accommodations, but enjoyed the same sights as the rich tourists and always had enough to eat. I don’t know how my father managed this journey on meagre funds, but it must have taken a lot of enterprise and perseverance. Admittedly, having a small boy in tow would have generated sympathy, and the world had not yet become overcome by refugee fatigue.

We lived in Istanbul for about a year and I have happy recollections of the city and its residents. Since we were in the first small group of refugees to reach Turkey, we were the subject of a first-page article, with a photograph, in the major Turkish magazine, Yedi Gün. We arrived half-expecting the Turks to be backward, Oriental and anti-Christian. In actuality much of Istanbul was already a modern city, with many Christian churches and American cars and, contrary to the standard Hollywood image of Turkey, not a single fez or face veil in sight. We saw the usual tourist sights, including the Hagia Sofia, the Topkapi Palace Museum and ─ most interesting to an eight-year old boy ─ the giant cannon with its huge stone cannonballs that the Turks used to breach Constantinople’s walls in 1453. I admired the sleek white passenger ferries that plied the Bosphorus, and acquired a taste for Turkish cooking.

We were pleasantly surprised by the Turks’ friendly attitude towards us, since they had been thwarted by the Poles in their several attempts to conquer Christian Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The friendship developed in the nineteenth century when we shared the same principal enemy, Russia. The story is told of a nineteenth-century Turkish sultan who found a way to publicly assert his refusal to recognize the partitions of Poland and the usurpation by the Tsar of the title of “King of Poland.” At the Sultan’s annual reception for ambassadors, he ostentatiously inquired, after greeting the Tsar’s envoy, “And where is the ambassador of the King of Lechistan (Poland)?”whereupon the Russian stomped out of the hall.

The friendship with Poland extended into the Second World War, insofar as the Turkish government continued to recognize the Polish government-in-exile, even though the state ceased to exist. The Polish consulate in Istanbul stayed open, with its flag flying, not far from where the German one flaunted its giant swastika. Since it happened that the Polish consul had a daughter of my age, I was often invited to his residence, picked up by the consul’s chauffeur-driven convertible with the Polish flag on its fender. The chauffeur always chose a route that took us in front of the German consulate. I imagined that this must have caused some gnashing of German teeth, and I had never again enjoyed a car ride as much.

In Turkey I also saw a unique, and probably now extinct system of shopping. In the morning, vendors led donkeys laden with groceries from house to house, most of which had second-floor balconies enclosed by wooden latticework screens. From there, the housewife would lower a shopping list and money in a basket, which was then filled by the vendor and pulled back up with the change. Thus the lady would remain unseen, preserving her Islamic modesty without violating Atatürk’s ban on face veils — an admirable arrangement on all counts. The donkeys were usually adorned with turquoise stones, to protect them against the “evil eye.” Many years later that memory prompted me to buy my wife a turquoise ring, which she liked a lot, until I confessed to its provenance.

I attended a French school where I learned basic French and some Turkish. I was since able to improve and maintain my French, but all I remember of Turkish is counting to ten. Most young children seem to be able to learn languages painlessly through instant immersion; only when they have to start by memorizing rules does that the process become unpleasant and usually unproductive.

In Istanbul I also had a brief interlude in an English boarding school, complete with blazers, school ties, and mandatory sports, but also the less attractive conditions for which English boarding schools were renowned. Laboriously, I wrote a pitiful letter to my father, begging him to take me back — not unlike Winston Churchill’s many letters to his mother from his boarding school, but I was even more desperate than he. So I borrowed the price of a ferry ticket and fled back to my father on the Asiatic side of the Bosphorus. I am sure there have been many other boys who ran away from boarding schools, but none, perhaps, who fled as an eight-year old from one continent to another.

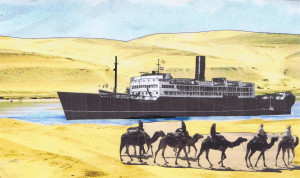

As Hitler seemed to pursue us by advancing into the Balkans in 1940, we moved further south to the nearest British possession, Palestine. In Jerusalem I attended another French school, where I also learned basic English and a smattering of Arabic, including the all-purpose phrase inshallah (God willing) ─ a perfect way to express intent without commitment. It would be invaluable to politicians of all nationalities and political persuasions. I had my First Communion in Jerusalem and prayed at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre ─ a regrettably modest and cramped building, especially when compared to the golden-domed Al-Aqsa mosque nearby. In Jerusalem we became part of a group of refugees sent all the way to Livingstone in Northern Rhodesia. The voyage began with a train to Suez running alongside the Canal; we were treated to the incongruous spectacle of seagoing ships seemingly sailing through sand dunes and camels. In Suez we boarded the Cunard liner Mauretania, on its way to pick up Australian soldiers, which dropped us off in Durban. From there we took a first-class train for a two-night trip to Livingstone. One of my lasting memories is of falling asleep in a comfortable bed to the clickety-clack of the rails and waking up to the hiss of steam as we stopped at a station.

We spent a couple of years in Livingstone, within hiking distance of Victoria Falls. We had some happy times at the Falls watching troops of monkeys and baboons congregating in the hope of handouts from sightseers, or of snatching their sandwiches. We also heard the sad story of a foolish man who had an encounter with a carnivorous fish while swimming in the Zambezi without his trunks. The Town of Livingstone had an interesting system of sewage disposal. Instead of sewers there were outhouses, equipped with large pails − “thunder boxes” − which were emptied every night by a crew with a truck.

Our accommodation in Africa: mud walls and floor, palm leaf roof, no electricity, water or plumbing. But no heat was needed. (The two people are a friend and his mother.)

In 1942, during the brief thaw in Polish-Soviet relations in the interval between Hitler’s invasion of Russia and the discovery of the Katyń massacre, some thirty thousand members of Polish military families that had been deported to Soviet Kazakhstan were allowed to leave the Soviet Union and sent, via Iran, to Africa. To house them, several camps were created where inexpensive accommodations were quickly built in the form of rondavels, the Africans’ standard round mud huts with thatched roofs. They had no electricity or plumbing, but needed only the locally available building components in plentiful supply: unskilled labour, mud and palm leaves.

Our small group from Palestine was moved to one of those camps, in Lusaka. Polish elementary and high schools were set up and functioned until the camp was wound up after the end of the war. That ended my formal education at Grade 9 level. In the absence of a school I read a lot at the local library, mostly history. That may have been a more effective way of learning a language than conventional second-language classes in high schools − judging by my grandchildren’s degree of fluency in French. In any case, my experience refutes the popular belief that changing schools and having to learn a second language impairs a child’s command of his first, and accounts for all sorts of problems, from juvenile delinquency to drug use to teen-age pregnancy.

Hitler’s defeat and the end of the war did not bring us Poles much joy or relief, since it became clear that our country would be merely trading occupiers. The Yalta Conference of Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin in February 1945, placed Poland, along with the rest of Eastern Europe, firmly in the Soviet “zone of influence”, which meant the imposition of the communist system and Stalin’s total control. Churchill made a half-hearted attempt to dissent but was in no position to stand up to Stalin, and Roosevelt couldn’t care less about Poland; Polish-Americans did not have a lobby in Washington. Thus, the dream of returning to a free country died with the Yalta surrender. About half of the Polish refugees in Africa saw no alternative but to resign themselves to Stalinist rule in the new “People’s Republic.” The others, including my father, who could have been, for many reasons, labeled “enemies of the people” by the Reds, were determined to find other countries to settle in.

This image is my own composition: The passage through Egypt: sea-going ship sailing through sand dunes and camels.

As the camps were being wound down, we kept getting transferred and finally wound up in Tengeru, near Arusha in Tanganyika, to await immigration opportunities. The trip to Tengeru included passage on a ship with an Italian crew who would gather on deck every evening to serenade us with song, which they did magnificamente. (It was lucky for the Allies that the Italians’ military prowess did not always live up to the quality of their singing.) On the final leg of that trip, we saw the semi-annual migration of thousands of wildebeest and zebras on the Serengeti Plain.

From Tengeru I could see the upper, snow-covered half of Mount Kilimanjaro, which seemed to hover in the distant haze. More recent photographs of the mountain show that most of the snow has melted, leaving a mere skullcap at the top. I learned some Swahili, including the phrase akuna matata, which translates as “no problem,” but was often used as the equivalent of the Mexican mañana, or the Cockney don’t get yer knickers in an uproar. But I didn’t have to speak Swahili to buy fruit from Masai vendors; they had learned Polish: “Pani, Pani, dobre banana!.” By the way, bananas were the cheapest food available: one pence a dozen.

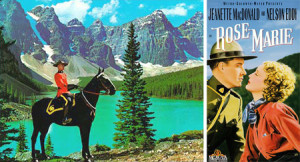

How I saw Canada: The Rockies, a beautiful maiden and stalwart Mounties who always got their man (and did not have to use a taser)

In Tengeru I read a Polish pre-war travelogue about Canada, which painted the usual picture of the snowy Rockies, majestic forests, golden prairies, serene lakes, and gallant Mounties. Then I saw the movie Rose-Marie, in which Nelson Eddy serenaded Jeanette MacDonald with “Indian Love Call.” So, when a Canadian mission arrived to recruit able-bodied immigrants for work in Canada and invited me to apply as well, I did not hesitate. I signed a contract with His Majesty’s Canadian Government, granting me resident status in Canada in return for my undertaking to stay for at least one year in a job chosen for me by the Department of Labour. I packed my modest belongings, and without asking my father’s permission, boarded the ship for Canada.

The ship, the General W.M. Black, was a former grain carrier converted to a U.S. Army’s troop transport, with the most basic sleeping and eating arrangements. The American crew’s attitude towards us made it clear that new immigrants did not quite have human status in their society. However, I consoled myself with imagining the exciting new life I would be leading in Canada ─ as a trapper, a lumberjack felling huge trees with a mighty axe, or at least a cowboy.

I arrived in Halifax in August 1949, still wearing my standard African Bwana Big White Hunter outfit, including a pith helmet. I threw the helmet overboard in the harbour and went ashore to get acquainted with my new country. It was a Sunday afternoon, and walking through a residential neighbourhood, I could see few signs of life in the street or the houses. Having arrived from Mombasa, which was full of people and constant noise, I wondered if Halifax had been evacuated in anticipation of a nuclear attack. Only later did I find out that most Canadians observed a quiet Sabbath in those days: church in the morning and reading the Bible in the afternoon (or that was the official story anyway. Some cynics claim that the real activity of those long afternoons, before television, resulted in the high birthrate of that era ─ a vile calumny, no doubt. Honi soit qui mal y pense.)

We took a train to Ajax in Ontario, where the barracks built for munitions workers during the war provided a holding centre for shipments of immigrants. From there we were sent to our jobs: males to farms, and females to domestic work. While I waited for my turn, the few new friends I had made on the ship left, one by one.

On September 2nd, 1949, almost exactly 10 years after the start of my journey, it was my turn. I found myself sitting in an empty room at Toronto Union Station, waiting to board a train to take me to Collingwood to report to my new employer. I had never felt so utterly alone; by then I had lost contact with anybody I knew, even the few casual acquaintances I met on the ship. I felt totally separated from the rest of mankind, as if watching the world through a one-way window.

In Collingwood I was met at the railway station by my new employer, John K. Currie. His surprised response to my greeting was. “So ─ you speak ! … But you are just a kid!”

The reluctant cowboy: me on the farm — after I was promoted from shovelling manure to driving a tractor.

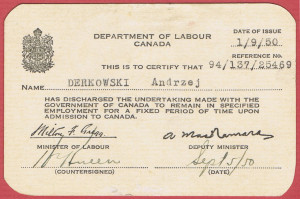

I am sure that he would have gladly traded my ability to speak English for more muscle and callused hands. John had a dairy farm, so it turned out that I did become a cowboy, although not of the Hollywood variety; instead of a six-shooter, I was given a manure shovel. Nevertheless, I tried to do my job as well as I could and stayed on that farm for the full year. Some of my former shipmates fled from their farms to the city as soon as they could, but I was determined to fulfill my obligation. I earned a document certifying that I had “… discharged the undertaking made with the Government of Canada…” which I am proudly displaying beside my diplomas. It was the toughest one to earn.

This was the first diploma I got in Canada — and the toughest one to earn.

As soon as my year was up, I set out for Toronto, where I started a long climb from the bottom rung of the socio-economic ladder. Luckily, I was able to board the rising rocket ship of Toronto housing prices early, and thanks to the opportunities provided by Canada, plus many nights and weekends of part-time study, I gained a measure of prosperity, a degree in urban planning, and three children and six grandchildren. And I built a cabin on a northern lake reminiscent of a setting from Rose-Marie.

In the process I became, in the words of the winning entry to one of Peter Gzowski’s contests on CBC radio, “as Canadian as is possible under the circumstances.” I learned to end sentences with eh?, paddled canoes, shoveled snow, grumbled about the cold in the winter and the heat in the summer, fed chipmunks and blackflies, tried fiddleheads and poutine, drank gallons of double-doubles, mourned the demise of the Avro Arrow, and cheered when the maple leaf flag was first raised.

Sadly, I admit that I have never quite mastered skating, eaten a prairie oyster, or tried that ultimate test of Canadian-ness involving a canoe and a co-operative partner.

CR

What a colourful and inspiring journey, Mr. Derkowski! I loved the sense of humour in your piece and found myself chuckling regularly while reading.Thanks for sharing!

Delightful to read this well-written, world-spanning adventure — the life of a gentleman I’ve known until now only as an amateur historian and a very clever poet. Many thanks, Andrzej!

I happened upon your article looking for information for my mother in law, she has just learned that her birth parents are of polish decent, her birth mother landing in Montreal in 1938 originating from Kaluszyn, Poland.

Your article is lovely and as the previous posts state “colourful and inspiring”

Thank You. I enjoyed it.

Pingback: Welcome to CR’s Fall 2013 Issue!

My father was Dutch and also survived WW2 Europe. Great to read about your exploits.Australia is I guess a much hotter and fly infested version of Canada and our family has been here 35 years now.

Just read the full book called Passage through turbulent times. Very good read Andrzej. An interesting and rewarding life to say the least. Well written with nice nods to history and humorous asides.

Good way of describing, and good paragraph to obtain information on the topic

of my presentation subject, which i am going to deliver in school.

My father, also Polish and 8 years old at the outbreak of WW2 had such a similar story to yours, up to and including travelling on Mauretania to Durban and being housed in Livingstone with most of his family. HE, however, went to Cape Town in 1945 to start high school and the rest of his family joined him later on – and remained. He never talked much about his exodus so it was really wonderful to read your story as he must have experienced much the same things as you.