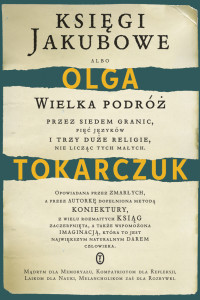

Księgi Jakubowe (THE BOOKS OF JACOB, or a great journey through seven borderlands, five languages and three major religions, not counting smaller ones)

by Olga Tokarczuk

Wydawnictwo Literackie, Kraków 2014

You wander into the pages of The Books of Jacob as you might stroll through a lively museum or explore a mysterious dwelling. Soon, the setting and the characters so grab you in the first fistful of pages (out of the book’s 900!) that you are left captive, spellbound. Here I was, a creature of the twenty-first century, living and breathing the air of the novel’s late-seventeenth century.

I kept reading the epic, off and on, through my three-week stay in a sanatorium. In barely a few days, I was in a haze: which was my daily life and which was the fiction? Of the two, Tokarczuk’s world was certainly the more compelling, the more multifaceted, its splendours more seductive. By contrast, the tedium of convalescent existence was unredeemed by the installments, on the news, of my country’s current, pitiful, constitutional psychodrama.

So I impatiently returned to The Books of Jacob. I seldom spoke to others, reluctant to disrupt Tokarczuk’s tale. And I rejoiced in the books’ heft, glad to weigh it in the hand, delighted at its pleasing, attractive presentation: a beautiful object, like an antique treasure box.

The story is that of an almost forgotten episode in the history of the ancient Polish Republic, namely the curious conversion to Christianity by a sizeable group of East-European Jews. This occurred in the declining years leading to Poland’s partitions, over a territory stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Among the area’s many peoples, Jews formed a tight, separate, well-knit society. Distinguished by their religion, customs, language and dress, they obeyed their own laws, governed their own institutions, set up their own state within each of the states where they settled. What they lacked, was their own land. Although not nomads, many of them constantly moved across vast territories, for business, for education, for visiting or in search of safety and peace. Throughout, they kept up their specific conversation with God.

It so happens that one of them, Jacob Lejbowicz Frank – an undaunted rebel roaming in the steppes of Podolia, today’s Ukraine – renounced the Talmud, proclaimed himself a Messiah, and sought

Jakub Lejbowicz Frank

enlightenment in the Book of Zohar, plunging into the Kaballah’s mystical revelations. His followers quickly multiplied and he finally led them, through a variety of political and religious upheavals, to baptism in the Catholic Church.

This charismatic figure is the book’s main character. The lively, eventful storyline rests on authentic historic events. We recognize facts and people remembered from familiar textbooks. But it is Tokarczuk’s writing we admire, so characteristic yet also full of unexpected twists. She spins unusual harmonies between narration, dialogue and reflection, composing her novel like a piece of music. Its rhythms seduce the reader. The narrators’ voices succeed one another in space and time, surrounding Jacob Frank and his widespread, thickly knit community – sometimes from the outside – but soon mixing in with the worshippers, swept up by history. We follow their footsteps. Sometimes, we’re caught off balance – since Tokarczuk’s world is like the one we live in: crystal clear at moments, at others romantically foggy. And the complex links between characters both appear — and disappear — from eyesight.

The author’s language is captivating, peering into deeper meanings and raising surprising flashes to the surface. At one point, for instance, she plays with the word ‘impatience’ and its various senses. Sometimes the reader must backtrack to check on a name, to correct one’s recollection of events or characters. Now we see everything through the eyes of Nachman, Jacob’s associate. Then through the prism of old Jenta suspended between heaven and earth, between life and dying. We are party to the story of Moliwda, a son of traditional Polish gentry, or follow the doings of two energetic women, Kossakowska and Drużbacka. We view the dilemmas of Chmielowski the priest, Dembowski the bishop, the notations of the parish scribe. Many of these figures existed, their biographies can be checked on Wikipedia. But Tokarchuk fleshes them out. She skillfully garbs them, surrounds them with their everyday objects, dwellings, landscapes – and hardest of all – manages to give each one his or her personality. Each has distinctive yearnings, ambitions, dismays, passions, pools of kindness and rottenness. Tokarczuk weaves this complexity into an impressive array of relationships.

The Polish women in The Books of Jacob ride firmly astride their surrounding reality, they anticipate events and steer them, they ceaselessly attempt to guide the lives of others. The Jewish women are carried by fate, they fascinate the senses, make reason waver, but they do not themselves try to bend fate. They are pliant to men on the surface but, well aware of men’s failings, they wield much power. These women, Chaya, Chana, Gilta, Avacha-Eva channel mysterious forces, they hold keys to the universe and to timelessness.

Even though the logic of events constantly yields to mysticism and the surreal, the book’s chronology abides by historic time. The men and women in these pages mature, age, pass away, memories of them fade and in subsequent generations are deformed.

I learned much from Tokarczuk’s book. Though the story owes much to the author’s fancy, it brings us close to the lives of Jacob Frank and his followers, the Frankist movement. Brilliantly depicted, this sizeable slice of southeastern European history singularly illustrates the entwined fates of Jews and Poles.

Closing the book, I wonder: what most amazed me ? Surely its skillful portraits of a community, revealing its lines of strength, and the ability of one man, a leader, to enhance and manipulate these various skeins.

The portrayed characters are convincing, the depicted events credible. The only thing I found doubtful was the leading superstition’s conclusion – not because it seemed over drastic, but perhaps a little too simplistic. Things may, however, so have happened. But I must refrain from jumping the gun, spoiling the plot.

Pingback: Welcome to Winter 2016!

Pingback: Bulletin Board Winter 2016