Radioactive: Marie and Pierre Curie, a Tale of Love and Fallout

Radioactive: Marie and Pierre Curie, a Tale of Love and Fallout

by Lauren Redniss

It Books; Harper Collins Publishers; New York; 208 pages

2010

Lauren Redniss has written a very modern portrait of this celebrated couple that is a treat to read. From the custom type created by the author to the layout of the sparse text to the illustrations, the author presents a biography that captures not only the linear progression of the lives of these scientific giants, but connects their work to its effects in the world. “Radioactive” is a work of art.

One key to the success of this book is the incorporation of numerous quotes of Marie, Pierre, and others. Actual words help the reader relate to the Curies and to their time. In addition, the accounts and testimonies of other sources linked to the Curies’ work help the reader understand the magnitude of their discoveries. This is especially evident in chapter 5 “Instability of Matter” in which Marie’s thesis that radiation may inhibit malignant cell growth is followed by the 2001 testimony of a cancer patient being treated for Non-Hodgkins lymphoma with a thermoplastic radiation mask. The same chapter included the development of the atom bomb, the Manhattan Project, a copy of declassified FBI files, and the testimony of a Hiroshima survivor.

As the story of Pierre and Marie Curie progresses chronologically through the nine chapters of the book, the author mirrors the characters’ personal and professional lives with other seemingly random events. For example chapter 7 “Half-Life,” begins with the tragic decomposition of bones of women in the United States who coated watch dials with radium, then progresses to the freak accident that kills Pierre, that is then followed by a description of the Three Mile Island disaster, weaving together the idea of a “normal accident.”

Inseparable from the text is the artwork. The cyanotype print process used in making the illustrations not only supports the text, but forces the reader to think about the subject. At first glance, the drawings appear simple, even grotesque, but they serve to engage the reader. Peppered throughout the book are photographs, maps, and charts that both strengthen the chapter topics and are primary sources themselves. Even the book cover is made from glow-in-the-dark materials, making the book itself seem radioactive.

One underlying theme of the book is the remarkable partnership of individuals who, working together, discover something new. At the turn of the century, an amazing confluence of scientific discoveries and ideas created an atmosphere where information was shared among scientists. Beginning with Pierre and Marie who never sought a patent for their discoveries, to Marie and Paul Langevin, then to Marie and her daughter Irene, then Irene and her husband Frederic Joliot, etc., these relationships clearly show the benefit of sharing ideas and how those ideas spread with a life of their own throughout the scientific community.

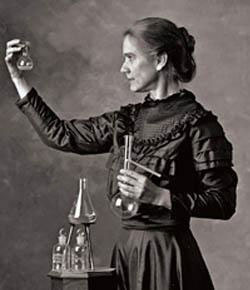

The book spotlights Marie’s great personal strength. As the reader follows Marie’s life, one begins to understand the tremendous challenges she overcame starting with her Polish childhood in Russian-occupied Poland. Her clandestine studies through the secret “Flying University” allowed her to acquire an education so thorough that she could ably compete as one of 23 women of 1800 students attending the Sorbonne. Conducting the physically exhausting work of proving the existence of polonium and radium, and later suffering through radium toxicity did not detract from Marie’s focus on scientific study and the raising of her two daughters.

Another challenge Marie met directly and seemingly without flinching, was the attack on her character by the French press after her affair with Paul Langevin four years after her husband’s death. She endured public humiliation of her exposed affair by Paul Langevin’s wife in 1911 and was cast as a dangerous foreigner and a “conniving tramp who had ensorcelled a married man.” The scientific community even warned her not to attend the Nobel ceremonies to avoid a scandal. Marie responded, “The steps that you advise seem to me a grave error… There is no connection between my scientific work and the facts of private life.” This quote, also featured as the prologue to the book, was precisely the struggle that she so nobly conquered. She ignored criticism, attended the second Nobel ceremony, and was invited to dine with the King and Queen of Sweden.

Because Redniss’s writing is so sparse and in places reads like poetry, so much about Marie may seem abbreviated, yet all necessary points are made. Although her maiden name is spelled Marya Sklodowska, rather than Maria Sklodowska, the importance of her Polish background is made clear. Of course the naming of the Curies’ first radioactive element polonium in honor of Poland is well known, but Redniss also includes a two page listing of famous Polish people, flora, and fauna. This apparent random listing, like other seemingly unconnected facts and details, help flesh out the story of the Curies and put their lives into a frame of reference. It made this reader curious to learn more about life in Russian-occupied Poland, the “Flying University” that educated 5,000 women and thousands of men during this time, the double standard for women, the theory of radioactivity, and even mobile X-ray units, the “petite Curies” she and her daughter developed during World War I. She was the first woman in France to receive a doctorate, the first female professor at the Sorbonne, and the first person to win two Nobel prizes.

“Radioactive” is a biography of a truly extraordinary couple, and an especially strong woman. Through this intimate portrait of their lives and the science they studied, the reader is especially drawn to Marie Curie and can see her at the center of a chain of events that define the modern age. Lauren Redniss not only captures the story of the private and professional life of Marie and Pierre Curie, but through her choice to link to concurrent events and subsequent effects of their discoveries, it is possible to begin to appreciate their impact on the world. “Radioactive” leaves a lasting impression.

CR

I came across this gorgeous book recently at a DC library. I borrowed it, of course, and have been reading it bit by bit. The artwork itself is amazing, while the content is rich, deep – and a total treat.

Pingback: 2011 – The Year of Marie Skłodowska-Curie