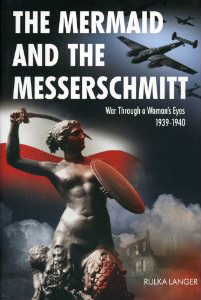

The Mermaid and the Messerschmitt: War Through a Woman’s Eyes, 1939-1940

The Mermaid and the Messerschmitt: War Through a Woman’s Eyes, 1939-1940

By Rulka Langer

Aquila Polonica, 468 p.

ISBN 978-160772-000-3

Anyone who’s ever read memoirs written during or immediately after the war knows how very different they are from those written many years later. The writing is vivid, unembellished, adrenalin charged. Memories have not yet faded, been tampered with. There is no editorializing. War is an experience unlike any other. Nobody comes out of it unchanged. When these experiences are recorded by gifted writers – and Rulka Langer certainly was that – they are at once harrowing, inspiring and breathtaking.

Rulka Langer’s The Mermaid and the Messerschmitt was first published in 1942, just months after she escaped with her two children from Warsaw, leaving behind her mother, friends and, although she didn’t realize it yet, a life that could never again be restored.

And what a charmed life it was. She was born into a wealthy family with aristocratic roots and women with an independent streak. She won a scholarship to Vassar College, one of the most prestigious colleges in America. Upon graduation she returned to Warsaw and worked for J.Walter Thompson, at the time the largest advertising company in the world, then for Polish Radio and later at the Bank of Poland.

She married, had two children, and continued working, unwilling to live as a dependent without an income of her own. The Langers were a lively, attractive couple surrounded by interesting people. When her husband was sent to Washington on an assignment with the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, she joined him for a while but found the life of a diplomat’s wife dreadfully boring. She returned to Warsaw, back to her job with the bank, with plans to join Olgierd again later.

This was in 1939, and there was much talk of war. Some people began stocking up on food, and carrying gas masks; businesses, including the bank, were making plans to evacuate; everyone was tense. Waiting for a war. But surely common sense would prevail?

When the war started, Rulka, like many of her fellow Varsovians, was confident. The Poles would stop the Germans; the British and French will help. But the news from the front was grim. The Polish army couldn’t hold back the invading Germans whose tanks and planes targeted peaceful villages, residential areas and unarmed civilians as fiercely as they did military targets. The allies did not show up; instead, the Red Army joined the Germans and attacked from the east.

In a gripping, fast-paced narrative, Langer describes the anticipation and dread, the panic and confusion, people in motion – to escape the bombing of the city; to escape the burning of peaceful villages and the strafing of civilians on the run; refugees laden down with possessions; refugees forced out of homes with nothing.

Still the siege goes on. Buildings in ruins; others standing, their outer walls blown away looking like a macabre theatre stage. Stores are emptied of food, long queues form in quest of bread. Dead horses are butchered on the streets where they lie; pigeons once joyfully fed by children become prey. The city prepares to fight the enemy building barricades out of trams, buses, and furniture, while volunteers man soup kitchens and prepare bomb shelters. But the bombs continue to rain down, setting buildings on fire, while low flying planes dip down to strafe people caught out on the streets.

The city landscape changes. Churches lose their spires, tall buildings collapse, bomb craters scar the streets while graves are hurriedly dug in parks, in the small green turf along some sidewalks, and finally in the sidewalks themselves. Makeshift crosses mark the graves, sometimes with names of the victims etched into the wood, sometimes with no identity. Almost miraculously, flowers appear on the graves during a lull in the bombing. And the siege continues. Hospitals, orphanages, schools, residences – nothing is spared. Finally, the water mains are bombed, the enemy’s final, decisive blow. People can endure much, but life without water is not possible.

Langer describes the devastation of the city but she writes primarily about people. People in their infinite variety, with their infinite ability to surprise. Only the very naive would try to predict their own behavior in a crisis. She witnessed heroism in people she had always considered timid, and cowardice among people who, before the war, had flaunted their boldness.

Langer didn’t spare herself. She was dismayed by her own response to hunger. Under extreme conditions, she who had been critical of looters suddenly found herself looting a bombed out house to get essential articles for her own family. In an unexpected bombardment she fled so quickly that she had forgotten about her own mother.

When the siege ended and the occupation began, the enemy that until then was an impersonal machine in the air was now seen face to face. Terrifying as the bombs were, the sight of a uniformed soldier beating young men, arresting women, shouting, shoving and humiliating people you knew, evicting and dispossessing your neighbors, these acts tore at the heart as acts of cruelty took on a personal character.

Langer’s book takes you to the centre of the drama, not just the way a war correspondent would, she explained, because a war correspondent, when reporting on a bombed city,”doesn’t leave his children behind in his hotel room… nor tremble for the life of his own mother… and it isn’t his own house that has been set on fire by the incendiary.”

“The horrors of war,” she writes, “come pretty much like the pangs of childbirth. At first, in spite of apprehensions, life still goes on, almost normal, with all its little trivialities. Then comes the pang: wild, screaming, inhuman. You think you’ll never stand it – yet you do. It passes – once more you are yourself. Trivialities reappear.” And so it goes, another and another. People die, and people are born. And no one will ever be the same again.

Langer escaped from Poland with her two children in 1942 when she obtained an American visa thanks to her husband’s position in Washington. She stayed on in America, going back to work for J. Walter Thompson. She returned only once to visit her beloved Warsaw, the city of the Mermaid.

CR

Pingback: Publishing the Greatest Story Never Told

Pingback: Bulletin Board Summer 2015

Pingback: Aquila Polonica to Publish Third Book