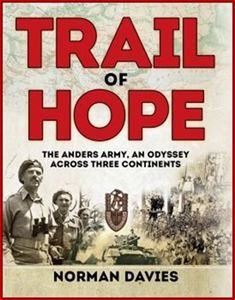

Trail of Hope: The Anders Army, an Odyssey Across Three Continents

By Normal Davies

Osprey Publishing (Oxford UK, 2015)

When I was very young, a classics course I took included Xenophon’s account of the March of the Ten Thousand, the story of a Greek army escaping from Persia. I no longer remember the details of the Greek-Persian conflict but I do remember that all of us, including our teacher, cheered for the freedom-loving Greeks, against Persia and its tyrant.

I alone in my class knew that Xenophon’s tale was but a short story compared to the saga of the Polish army that escaped from another tyranny, led to freedom by General Władysław Anders. The General’s name and image were known to me from my earliest childhood as a kind of collective godfather to all the children he had rescued. This was a military leader who knew precisely what motivated his men – my father was one of those men — and leaving the children behind would undermine their spirit. Possibly the only man who was never intimidated by Joseph Stalin, Anders insisted that they be evacuated with the army, and didn’t give up until the tyrant agreed.

But who would be our Xenophon? Who could do justice to this epic tale with its cast of over a hundred thousand men, women and children and their encounters with so many cultures spread over all the earth’s continents; the hardships and the battles; the beauty of the lands and the friendship offered along the way; the excitement of seeing new worlds… and finally coming to terms with loss?

But who would be our Xenophon? Who could do justice to this epic tale with its cast of over a hundred thousand men, women and children and their encounters with so many cultures spread over all the earth’s continents; the hardships and the battles; the beauty of the lands and the friendship offered along the way; the excitement of seeing new worlds… and finally coming to terms with loss?

The task fell to Norman Davies, who felt a comprehensive study of Anders was long overdue. Failing to interest a publisher in an academic work, he chose a popular style that in many ways does more justice to the texture, the colour and the drama of this incredible journey. He visited many of the sites along the Trail accompanied by the photographer, Janusz Rosikon.

Masterfully combining personal stories with the historical record, Davies weaves a tapestry that gives equal prominence to politicians and statesmen – the knaves and the rogues, the valiant and the stoic, the pompous and the duplicitous, the liars and the dupes – and to ordinary people – mothers and children, youth and the elderly, soldiers and teachers, the strong and the dying.

The Trail begins in Poland with the forced removal of Polish citizens from their homes to be sent into exile in the vast Soviet empire. Davies follows the trains to the camps and prisons throughout Russia and its subject republics. North to the region around Archangel, east to Central Asia, the steppes and deserts of Kazakhstan, farther east still to the camps of Magadan and north east to the gold mines of Kolyma where the survival rate was 10 percent. There is scarcely an area of the Soviet empire that doesn’t have mass graves, the remains of watchtowers, and barbed wire. As the Polish writer Ryszard Kapuściński noted, this country that failed to provide basic comforts for its citizens managed to surpass all others in the production of barbed wire.

Unprepared for the 1941 attack by his then ally, Hitler, Stalin needed the Western allies who in turn needed him. Included in their agreement was a demand for the release of his Polish prisoners. An “amnesty” was declared. Thousands of Poles could leave their camps, but they had to fend for themselves. They set off, marking out new trails, by boat, makeshift raft, trains, carts and their ill-shod feet all in search of that “Trail of Hope” and the Polish army that promised life and liberty.

Generals Sikorski and Anders in Iran, 31 km to Tehran, 4371 to Warsaw

One pictures this great migration across that immense country with its ever-changing topography, ancient cities – Samarkand, Ashhabad – as well as collective farms, environmental degradation, and primitive settlements of mud huts and the tents of nomads.

In time, the disparate routes came together in Uzbekistan, to the Caspian Sea and a flotilla of filthy crowded barges that would take them Persia (Iran). Hundreds of thousands did not make it, some never released from their prisons, some buried in unmarked graves, others working “for bread” until, by some whim, the Soviet authorities allowed them to return to Poland. For many that did not happen until after the death of Stalin.

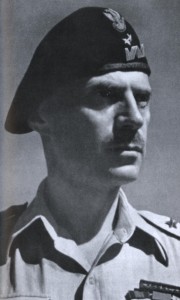

General Anders discussing strategy, Apennines 1944

Trail of Hope is not history “from above.” This is the story of a people, and few historians have such respect for the men, women, and children who endured, resisted, overcame or succumbed to the deadly force unleashed by war. They are not an undifferentiated mass, they are not labeled or placed in some arbitrary categories. They are people with all the diversity and dignity the word demands.

Still, the context is nothing less than World War II. But you don’t get the standard war of tanks and bombs as seen on the History Channel. Instead you get much more of the geopolitical currents of the time, and an unembellished picture of familiar figures: the dictator responsible to no one; the prime minister struggling for victory even as his country’s empire is coming to an end; and the ailing leader of a young and strong country indulging a delusional fondness for the dictator.

General Rudnicki leads the liberation cavalcade in bologna

Iran, the first stop in freedom, was a den of intrigue, the “Powers” competing for influence in a region awash in oil. The Shah was deposed, his son installed in his place. Iranians were not consulted.

The Middle East, then as now, had its politics and these were added to the complex Polish relations with Britain and with Russia. Stalin, intending to keep the Polish territory he annexed in 1939, recognized only “ethnic Poles” – but not Jews and Ukrainians – as Polish citizens. Still, some 6-7 thousand Jews did join, despite NKVD obstructions. Anders was adamant that Jewish volunteers be accepted, though some of his men were not welcoming. The General demanded unity; he prevailed.

Ukrainians who were Polish citizens often enlisted by concealing their identity (conveniently losing their documents). Once out of Russia, they resumed their identity and Uniate clergy joined the ranks of Roman Catholic, Jewish and Protestants chaplains.

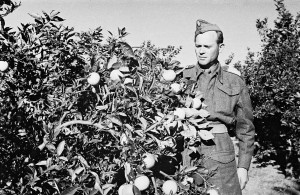

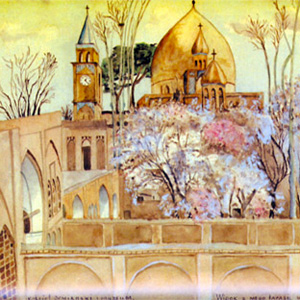

Definitely not Siberia

For their part, the British were wary of an influx of Jewish soldiers into their troubled Mandate Palestine. And indeed, about half deserted once they got there. Despite British pressure, Anders refused to pursue them as deserters. The most famous defector, Menachem Begin, was spared that label when Anders accepted his resignation, and the future Israeli Prime Minister returned his uniform. The Jewish civilians (the Children of Tehran) evacuated from Russia with Anders were also settled in Palestine.

On a lighter note, Anders’s men enjoyed entertainment by some of Poland’s best pre-war cabaret stars, many of them Jewish. After the war, they settled in Israel where a large Polish-speaking audience welcomed them.

En route to Iraq

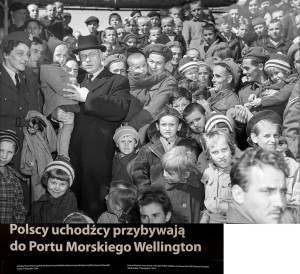

The Trail continued, but now with a new energy and sense of purpose. The civilians found refuge in the splendid city of Isfahan, in Beirut and Palestine, in India courtesy of two Maharajas, in what was then British East Africa, in New Zealand and in faraway Mexico. All of them waiting for the war to end so they could go home and rebuild their devastated country.

In the Middle East, while Anders strengthened his army, education was provided for the young recruits and cadets who had missed several years of schooling. Among their stellar teachers were Jerzy Giedroyc, Wiktor Weintraub and Melchior Wańkowicz. Egalitarianism ruled, distinctions between the well-born and the poorest ignored.

Polish orphans welcomed to New Zealand by Prime Minister Peter Fraser

The Anders Army distinguished itself in the Middle East, in North Africa and finally in Italy. There, Anders told his soldiers, “You will walk the trail well-known in Polish history, from Italy to Poland” — z ziemi włoskiej do Polski — as sung in the Polish national anthem.

Alas, it was not so. Chapter 18 is poignantly titled, ”From Italy to Nowhere.” The interests of the “Great Powers” prevailed. The Trail once again broke up into a great many disparate routes. The Communist regime revoked Anders’s citizenship, fearing his return would inspire resistance.

In the final chapters, Davies visits survivors or their descendants wherever fate took them. He surveys the literature on the subject, some of it by outstanding writers. He also lists archives that have been barely touched, all awaiting a curious, passionate, and ambitious young scholar.

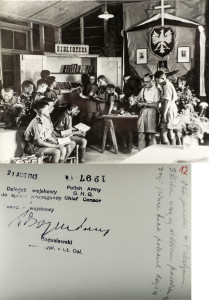

Junacy in the biblioteka

Trail of Hope is a wonderful book, richly illustrated – rescuing many photos from private collections — a significant resource in itself. While telling the story of an odyssey without equal in modern times, it is also a social history, a story of human relations.

Davies calls Anders “a great man,” and so he is. A loyal ally, an inspiration to his soldiers, and a father figure to thousands of children, they don’t make them like that every day.

This is a war story like none other; a war story equally about civilians and soldiers. It is about soldiers who shared a part of the meagre pay to contribute to the support of the orphaned children scattered across India and Africa.

For those of us who were children at the time, we remained forever in awe of the courage, strength and resilience of our soldiers, parents and guardians. If your family was part of the Trail of Hope, get a copy for every one of your grandchildren.

As for the rest of our readers, I can only add that this journey makes the adventures of Paul Theroux read like a package tour to a Club Med.

Tamerlane’s tomb, Samarkand

Anders portrait in the Sikorski Museum, London

All images courtesy of Rosikon Press, Warsaw

Pingback: Welcome to Winter 2016!

Irene, I just wanted to say that your latest issue is superb, beginning with your review of “Trail of Hope” – which I’m anxious to get my hands on as soon as I can – and John Guzlowski’s memoir.

It’s a bit of a poignant reminder for me because my mother, 88 in a couple of months, has been suffering from dementia for more than a year but recognizes her family and her long-term memories of childhood, Soviet enslavement and time in Africa are still vivid. One irony – and delight for us, is that her natural sweetness and kindness is so emphatic now, despite her wartime ordeals and sufferings.

My uncle Jan (my mother’s brother) is 93 and living on his own in Kingston, Ontario; I visited him recently and he was telling me about having to hurriedly bury his father (my grandfather) somewhere in Uzbekistan. He died of dysentery. My uncle Jan, who later fought at Monte Cassino, said these words are burned in his memory: “Hurry up and leave or you’ll get infected and die, too.”

My mother came from a family of eight, half of whom perished (her parents and two siblings) as a result of the Soviet deportations.

I am so pleased and grateful that you, Norman Davies and John Guzlowski and others are continuing to disseminate these stories. And you are so right, get copies of Davies’s book for your children and grandchildren.

Best regards,

Stan

What a wonderful review – I really enjoyed reading it. Thanks so much.

ed. note: Aleksandra Gruzinska, a “Barcelona child” http://cosmopolitanreview.com/poles-in-barcelona/ asked us to post hits comment from her:

Trail of Hope: The Anders Army, an Odyssey Across Three Continents – I especially appreciated your review of the Norman Davies book and plan to order it for our University library. One paragraph needs to be added – Gen. Anders’s extraordinary undertaking of sending a group of 120 Polish children from Italy to Barcelona, Spain. I doubt Davies knows about it. (Few people do.) Anders cared very much about this group and made it a point to visit the children in Barcelona. When I read “Trail”, I will concentrate on the Yalta episode where a great American President, very sick at the time, condemned Eastern Europe to 40 years of communist domination behind an impenetrable iron curtain. AG

I thank Mr Davies very much for writing and publishing this book but I really wish someone had done it 50 years ago for both our parents and their children:-

It took me a whole lifetime to understand my parents and their family friends and this book certainly would have helped a lot. Everyone wrote us out of the history books, we were the “Lost Polish Tribe” for so long, and even now how many mainland Poles still suffer from their ex-Communist amnesia about us and smugly inform us that we are not really “true Poles” but merely “persons of Polish ancestry”? The simple fact is that the Free Polish forces of the West preserved the traditions and character of the Second Republic much better than did the Poles who languished under 40+ years of Communist oppression and we their children are the surviving custodians of those traditions and that history and their gentle bravado and strong spirits which carried them through so much misfortune and so very different from the fearful collective neurosis of modern Poland and its misguided political leaders still fighting old battles which have already been won instead of focusing on the future:- we can certainly teach them a thing or two and we are just as “Polish” as them although we have become a very different kind of Pole out here in the wider world of Polonia Expatria.

If you look at page 400-401 in the book you will see a picture of a Sherman tank rolling through the Egyptian desert and standing in the turret you will see a young lad projecting a look of youthful determination which just says “Polska Odradzająnca!”:- that young lad was apparently my late father, Henryk Chamot, age 16 and he apparently did not reach his 18th birthday until after May of 1945 when the war ended and by then he had at least 2 years of military experience including at least a year of actual combat service (including his share of shrapnel wounds and the type of little “medals” which only combat soldiers are “awarded”) even before he was “legally” old enough to be in the army. There were hundreds (and possibly thousands more) like him along with several thousand women (including 5,000+ truck drivers), and a very diversified group of men of all ages and from every type of background and of course one 500-lb Persian brown bear who “joined” in Palestine and became a naturalized Pole and all regimented into a small under-strength army which “punched well above its weight”:- was there ever a more improbable and impossible project than the Polish Second Corps?:- Polonia Dominat et Omnia Vincit!

Btw, Pani Irena, you imply somewhat that General Anders was motivated to take Polish orphans with him only to keep his troops in good morale but actually he really did it because it was the right thing to do regardless:- Firm and united let us be, rallying round our liberty, and in our Polish kinship joined, peace and safety we shall find!

General Anders himself was a quite interesting person and unfortunately this book does not quite do him justice:- he came from a Polonized Baltic-German family and he was a Lutheran and his first wife was also from a Polonized European ancestry and was also Lutheran and actually a divorcee. They were happily married for 20+ years and they had two children but his first family became separated from him during the war and were trapped in Warsaw during the German occupation and even managed to survive the Warsaw Uprising before they finally emigrated to join General Anders in Italy where his wife became involved in Polish expatriate community work and public service. Unfortunately his first marriage also became a casualty of war and they separated amicably and General Anders went on to marry a second wife and start another family:- you can read about it in a little book published posthumously in Polish in 2007 by his first daughter, Anna Anders-Nowakowska. For most of us General Anders was a semi-mythical Polish version of “George Washington” but he had a private and very human life of his own and also had to worry about the fate of his family in Warsaw for several years with no information and Mr Kaczynski et al please note:- there are many ways to be “Polish”, we are not all neurotic virginal ultra-dogmatic Catholics who cannot speak anything other than Polish and with a very limited view of the wider world.

Finally, yes, it would be fine for one or more young scholars to continue this research and write still more about the Polish Second Corps but what this book really needs is the last missing chapter, Chapter 21, the one titled “Wracanie” as in “Kiedyś wracami do ojczyzny!”, a theme which preoccupied our parents so very much, and now it’s our task to write that missing chapter and to fulfill the old prophecy of the “missing” fourth verse of the original Mazurek Dąbrowskiego which was written 219 years ago for another exiled Polish army.

Irene, you are right in calling Norman Davies “Our Xenophon”. It’s a very apt description. Congrats to you for a very brilliant review of his latest book that deals with the epic “Odyssey Across Three Continents”. It is a story that needed to be told and was told superbly by a great historian, Norman Davies.

Pingback: The Africa Connection

An incredible journey well told. My father was with Anders. My mother and sister followed his army to get out of the USSR. Wonderful review.

Many thanks to Norman Davies and yet,sadly,the history of those days can never be complete.My Father left us on 12/10/42 to join the Polish Army in Kyrgistan,walking 60 kilometres because transport was unavailable.My Family survived through my Mother’s efforts and the unstinting help of the soldiers in Blagovieshchanka(14p.p.).

I can only repeat “Thank You”.In our case history’s circle almost closed by my son’s recent business visit to that country.

The reason many of Anders’ soldiers did not “welcome” Jewish “volunteers” is that it was well known that numerous Jews in eastern Poland had ostentatiously welcomed the Soviet invaders. This was widely known, especially since the exiles were from the Kresy. They were rightly regarded a traitors. Since the reviewer fails to mention the specific geographic origin of the exiles the reader is either misled or left wondering.

Would a stuffy footnoted study have done more justice to the truth of the story?

Gromada’s “very brilliant” usage is typical. “Brilliant” is a superlative requiring no qualifiers; he implies other degrees of brilliance and thereby loses contact with any real-world referent, thus consigning his usage to the logical positivist category of nonsense. Where was the editor?

Richard Adamiak Ph.D.

Excellent review. My mother was one of those thousands for whom Anders was little short of a god. If he hasn’t got one yet, then Norman Davies deserves a medal.

Wonderful review. It is all so very interesting for me. My father, Theodor Piotrowicz, was in Anders Army. Sadly he died many years ago. This book gives me the opportunity to now find out more details of his service under General Anders.

Thankyou

The reason why many of Anders’ soldiers did not “welcome” Jewish is that many Jews in eastern Poland had welcomed the Soviet invaders attacking Poland together with Hitler in September 1939. They were simply traitors.

Marek Stepczynski Ph.D.

My father Bolesław Szaler was in Andes Army.Unfortunatly he died in 1974 very far from his lovely land Poland, in Buenos Aires.Since 1939, as many other peole he was captured in Stanisławow, arrested imprisioned in Lwów and sended in Forced Labour Camp at Chabarowski.After amnesty he enlisted Anders Army.This book can help me to know how wartime was in those terrible years.I am so pleseant and grateful to learn trough this great and interesting book.Thanks a lot for ever !!