Tom Frydel has long been interested in the impact of the German occupation on civilians, especially in rural areas. He looks at Poland under occupation, or the General Government, as Nazi Germany chose to call it, as a laboratory of human behavior in extremis—extreme violence, extreme cruelty, extreme fear, all without respite on a scale impossible for the modern reader to comprehend. Think ISIS. Given a growth of academic interest in trauma, it is remarkable that scholars have largely neglected this aspect of the occupation and its relationship with local attitudes toward the Holocaust. Yet there is much to be learned from the archives – both from real-time documents produced during the war and from the records of over 30 thousand postwar trials. He shares below some of his findings on the situation in the region around Markowa, which will in time be the basis of his planned book.

On March 17, 2016, a long-awaited museum dedicated to the history and memory of Poles who rescued Jews under German occupation was officially opened. Located in the village of Markowa in the Subcarpathian (Podkarpackie) region of southeastern Poland, the museum was inspired by the tragic fate of the Ulma family of eight, including the pregnant wife Wiktoria, and members of three Jewish families—the Goldmans, Grünfelds, and Didners—whom the Ulmas were sheltering. The Polish family was ultimately denounced and both Poles and Jews were brutally murdered by the German police in that very village on March 24, 1944.

The Ulma family

The opening of the museum was celebrated by Polish diplomatic posts all over the world. In Toronto, members of the Polish and Jewish communities of Ontario gathered in Congregation Habonim—a fitting location, as it is one of the first synagogues in Canada founded by Holocaust survivors, some of whom were present during the ceremony. The moving event was organized by Toronto’s Consulate General of Poland, Congregation Habonim, and the Polish Jewish Heritage Foundation. It was the local character of the event that provided the most moving highlights. One suspects that the success of the event owes much to the sensitive charisma and openness of rabbi Eli Rubinstein, who choreographed the event with great care. Among the audience were members of the Riesenbach family, whose ancestors, Yakel and Eta, survived the war in Markowa, sheltered by the Bar family.

Little was known about the tragic events outside of the small community until the 1990s, when Józef and Wiktoria Ulma were posthumously given the titles of Righteous among Nations by Yad Vashem in 1995. Since then, in the Polish pantheon of national heroes, the trajectory of the Ulma family has been aimed at near-sainthood, especially as the Catholic procedure for beatification has been initiated. In fact, the museum is bound to become a pilgrimage destination and national mecca of sorts. The very language used in the exhibit—the “Righteous,” “The Samaritans of Markowa,” and “Servants of God”—taps into an almost metaphysical narrative of martyrology that elevates this Holy Family of the Holocaust beyond the reach of history. Given this sacred aura, one hopes that the unambiguously named “The Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II” finds room for the story of the capture, torture, and robbery of the “Trynczer” Jews by their neighbors prior to handing them over to be shot by the police in Gniewczyna Łańcucka, no more than 20 km from Markowa – a story painfully told by one of its Polish inhabitants, Tadeusz Markiel.

The Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II

Research into the tragedy in Markowa and the broader historical context is beginning to reveal a story of occupational dynamics that is unlikely to fit neatly into commemorative practices. It represents but one aspect of a larger social dynamic surrounding the shelter of Jews. Take the testimony of Yehuda Erlich, a local Jew who survived by being hidden by Jan and Maria Wiglusz in the neighboring village of Sietesz (6 km from Markowa). In testimony given in 1978, he recalled the incident in the following way:

These were hard times for them [Jan and Maria Wiglusz] and for us. Searches were conducted both by the Germans and by the Polish peasants themselves, who wanted to find the hidden Jews. In the spring of 1944 a Jewish family was discovered hiding with Polish peasants. The Polish family – eight souls, including a pregnant wife – was killed [together] with the hidden Jews. As a result, there was enormous panic among the Polish peasants who were hiding the Jews. The next morning 24 corpses of Jews were discovered in the fields. They had been murdered by the peasants themselves, peasants who had kept them hidden during [the previous] twenty months.

Similar patterns can be found in other parts of occupied Poland – in some cases, on an even greater scale. For example, in the western part of the Subcarpathian region, part of the village of Podborze (Mielec county) was “pacified” for the shelter of Jews on April 23, 1943. By piecing together several postwar trials, it appears that at least 35 Jews were captured or killed, across three communes, within a week or so following the burning of the village. Villagers appear to have been seized by a communal fear bordering on mass hysteria or paranoia. When local Polish policemen arrived on the scene, they encountered peasants pleading them not to hand over the Jews for fear that they might betray their shelterers, but to shoot them on the spot instead. Crossing the threshold from witnessing to participating in killing appears to have been powerfully enabled by forms of extreme violence.

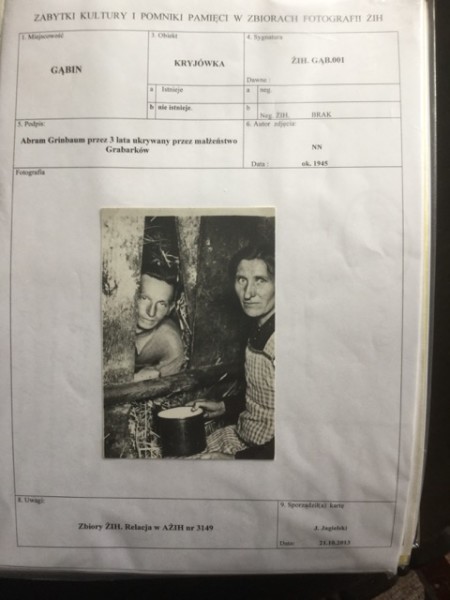

Abram Grinbaum hidden for three years by the Grabarków family

The documents reveal further complications. A monthly situational report dated to May 31, 1944 for the Przeworsk district issued by the Peasant Battalions (BCh), one of the most prominent partisan formations in the region, mentioned the Markowa event in the following way:

The Jewish element has been almost completely destroyed by the occupier in our district. A negligible number is still in hiding, but they are so well hidden that it’s hard to find any trace of them. Certainly more could have remained in hiding if it wasn’t for their poor tactics during interrogation when captured by the gendarmerie. In such situations, they reveal everything they know – whom they hid with, who gave them food. The accused face unfortunate consequences, including the loss of life, and so fall victim sooner. They almost always receive something to eat and a refuge, but after the tragic events, they [locals] officially distance themselves from them. Currently, apart from the incident in Markowa, not a single Jew can be seen anywhere. Those who are in hiding don’t show themselves in daylight. The Poles who shelter them are risking a great deal, but they are acting out of a feeling of civic duty.

Pointing to such factors is not to blame the victim in any way, but to place the events within a broader historical process. Incidents of such betrayal have their place in the narrative. For example, on December 4, 1942, German gendarmes had captured 18-year-old Małka Schönfeld some 15 km south of Markowa. She was hiding together with her family and a few Soviet POWs in a forest bunker. The German policemen took Schönfeld on a cart and drove through the villages of Pantalowice and Hadle Szklarskie, as she indicated who had given help, leading to the execution of nine villagers. Such incidents are captured in real-time documents of the period. Franciszek Kotula, who kept an ongoing chronicle of the “voice of the street” in the city of Rzeszów, made the following entry on December 16, 1942: “Rumors are coming in from all sides that the Germans are murdering entire Polish families if they discover any hidden Jews. Whoever is still hiding someone, they push that person out and, when captured by the Germans, the person most often reveals where he stayed and who gave him food. Even though he knows that he will face death anyway. A great panic has exploded among those who gave shelter to Jews and they escape into the woods.”

Yet such processes cannot be understood solely along an ethnic Polish-Jewish axis, though this is how they have been preserved. For example, in another part of the Subcarpathian region, in the village of Brzezówka, Aniela Mitał gave shelter to an escaped Soviet POW, who had jumped off a transport. When police arrived and did not find the fugitive, they shot Aniela Mitał and her two children. Their home was set on fire and the Polish village guards were ordered to throw their bodies into the fire. Such incidents set the general tenor of fear on the local level. In the context of Soviet POWs, we also find a similar dynamic between shelterers and the fugitives. In the July 1944 issue of the underground publication, Wieści, we find the following report:

Facing imminent danger, the unavoidable bullet, he [the Soviet POW] gives away the names of those who had previously given him food and refuge. […] There are only a few exceptions among Russian prisoners of war who responded to the Germans with silence and contempt during interrogation and the barrage of questions, without betraying those who helped them in hard times. The rest, although they know without a doubt that their fate is sealed, extend their life by a few days out of fear.

The motifs of German repression, the potential for betrayal by those being helped, and peasant violence were thus closely linked. A new teleology of murder arose from these conditions that was not rooted in ethnic hatred or antisemitism – though these were part of the picture – but in the social mechanisms of survival formed in the crucible of a brutal occupation. Sheltering fugitives proved to be an inherently shifting and volatile situation.

These are findings that will not satisfy those who expect a black-and-white story of perpetrators and victims, heroes and villains. In many ways, these behaviors have eluded historical categorization and understanding for decades. But those who are serious about remembering the Ulmas and understanding the dilemmas faced by Polish society under German occupation must contend with this dark chapter in its historical entirety, root and branch. However, the danger is that the findings will remain captive to a polarized historiography and a stylized understanding of Polish-Jewish relations obsessed with “positive” and “negative” portrayals. What remains to be written – remarkably, some 75 years after the events – is a social history of genocide in the General Government that contextualizes forms of violence against Jews with that of other fugitive groups and the social mechanisms that propelled segments of society toward participation. Only such an approach can give us a true measure of behavior that undermines any Manichean judgment or projection of contemporary morality into the past. In this social landscape, the story of the Ulmas emerges as the tip of an iceberg whose submerged body we have yet to fully fathom.

The village of Podborze right after the war showing burnt ruins of a village burned for hiding Jews

And we have the sources to write such a history. From 1944-60, approximately 32,000 trials of individuals accused of war crimes and collaboration were carried out in Poland. It is this documentary material that is giving historians a hitherto unprecedented look at the Holocaust in Poland. Still, the cases that pertain to the persecution and murder of Jews are but a fraction of this rich archival record. Thousands of these cases deal with peasant hunts for Polish laborers, Soviet POWs, partisans, and any other groups targeted by Nazi German policy from 1942-45. Researchers have only begun to scratch the surface of this period and the field remains open to dozens of dissertations, articles, and books that harness this rich material to a new understanding of Polish society under occupation. Beyond the enclosure of Polish-Jewish relations and national narratives, there is a larger story of human behavior in the shadow of genocide.

Events such as the one in Congregation Habonim should rightly hold a special place in the memory of Toronto’s local Polish and Jewish communities and their self-understanding. There is every reason today to recognize the Ulmas and the thousands of others who took on a similar risk and paid the price with their lives. But historians have an obligation to protect the emerging social history from a solar eclipse of national symbols.

CR

My profound thanks to Tomasz Frydel for empirically establishing a much-needed framework for accurately identifying and explaining the complex dynamics experienced by Polish society under Nazi occupation.

I also echo the profound thanks expressed by Mr Sokowlowski above.

The one thing that I cannot yet fully understand was the apparent willingness, by the Jews who had been discovered, to reveal which Poles had come to their aid, when the Jews knew that they (themselves) would be killed anyway, while also being aware that these Poles, who had risked so much, would also be killed. Words fail me here.

But I do wish that all those who have seen that severely biased film “Ida” would also read this article.

Thank you for writing this article and describing what looks like a very productive line of future research.

a Polish poor farmer with 7 Kids hide my father and 2 other Jews during II WW Wasilewski Francisek Yad Va Shem rejected to recognise him as rightous among the nation

Very good article. Unfortunately, the overall perception of Polish conduct under Nazi occupation continues to be characterized in mostly very negative terms worldwide with usually very little account taken of quite possibly the most extreme circumstances experienced by any wartime population. Inhabitants of western countries which were never subjected to brutal occupation simply cannot understand the life or death choices forced on a subjugated people.

Counteracting negative perceptions is very often an uphill struggle for anyone with Polish connections and part of the reason for this is probably because the complexity of the situation in occupied Poland defies any simplistic narrative treatment.

Would a popular film right some of these wrongs, as someone in the current Polish government suggested recently? If so, it would have to be a very long and complex epic, possibly a TV series in scope, to come anywhere near doing justice to all the issues – illustrating Polish flaws as well as Polish virtues – arising from the years 1939-1945.