Black Ribbon Day

Black Ribbon Day

By Edward Soltys

The Canadian Polish Research Institute 2014

A few years ago, Stanford University historian Norman M. Naimark published a short book called Stalin’s Genocide (2010). This stimulating interpretation, based on an earlier essay, garnered little attention outside of academia. In a dispassionate and impartial manner, Naimark explains why we must consider Stalin’s systematic acts of destruction of his own populace as genocide. His rationalization was simple. After the Second World War, the newly minted United Nations developed a narrow definition of genocide in order to avoid a confrontation with the Soviet Union which stood accused of a variety of crimes. On Stalin’s insistence, for example, the category of “class” was never included alongside the more recognizable racial, religious or national qualities that became a litmus test for classifying certain killings as acts of genocide. The liquidation and repression of kulaks (private as opposed to collective farmers) and enemies of the state could continue unabated.

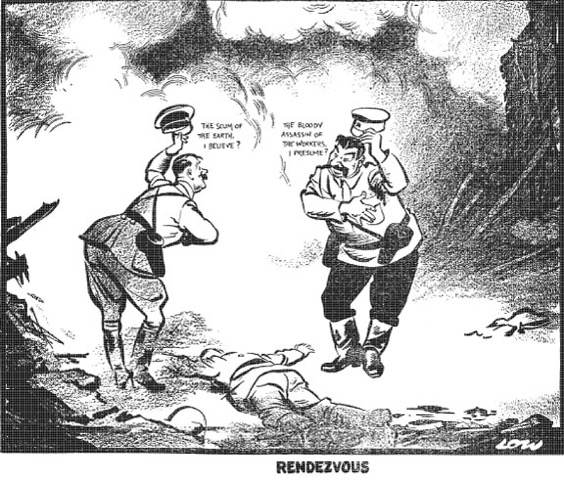

Naimark was frank about his motives when I heard him speak at the University of Toronto shortly after the publication of the monograph. He refused to accept the general perception that Stalin should not be compared to another infamous genocidal dictator, Adolf Hitler. In his eyes, Stalin was an equally merciless killer whose brutal repressive measures constituted more than mass killings – they were indeed acts of genocide. Naimark’s lamentation over the reluctance to place Stalin and Hitler in the same category is important. Poland offers an interesting—even if somewhat paradoxical—testament to this longstanding comparison of Stalin and Hitler in the broader collective memory of the Second World War.

The war remains a defining moment in the history of Poland. The 6-year conflict was triggered by Soviet-German collusion. The September 1st invasion from the West was followed two weeks later by an equally brutal invasion from the East. The Second Republic was once again partitioned by her two neighbours. Both the Gestapo and the NKVD went to great lengths to eliminate the political, intellectual and military leadership of the Polish nation. Both engaged in unspeakable acts of brutality. Yet, interestingly, the memory of the Soviets and the Germans role in the war has been preserved in the Polish national consciousness in diverging ways.

Two extensive surveys were conducted in Poland in 2000 and 2005 around the collective memory of the Second World War. The results were surprising and also telling. For the vast majority of Poles, the war is associated with two key facts: the German aggression on Poland and the Auschwitz concentration camp. Only a tenth of respondents pointed to the destructive activities of the Soviet Union on Polish territories. And only a mere five percent—one out of 20 participants—mentioned the Katyń massacre of Polish officers by the NKVD. The verdict was in: Poles had decided that the Nazi atrocities far surpassed those initiated by Moscow. Could this be explained by the four decades of Communist whitewashing of wartime history? Was this a product of an attempt to forget the humiliations at the hands of the Soviets, as for instance, Member of the European Parliament and of the PiS party, Wojciech Roszkowski, would have us believe?

David T.E. Somerville refused to remain reluctant about comparing Hitler and Stalin. A Scottish Canadian who plays the bagpipes and served as an officer in the 48th Highlanders, he was always dismayed about the “different treatment given to Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia by western politicians, media, intellectuals, movie-makers and other opinion leaders.” He could never accept that the Nazis were demonized for their actions while the Soviets were not. The true story of these “Partners in Tyranny” had to be told. The main obstacle was that anybody who raised such comparisons in the West was immediately branded as a “dangerous right wing extremist”. His refusal to glaze over the Communist atrocities led Somerville to become involved in what would become a global protest movement for freedom from Soviet oppression.

Somerville is one of the key protagonists of Edward Sołtys’s latest monograph, Black Ribbon Day, published by the Canadian Polish Research Institute, devoted to the roots and growth of the Black Ribbon Day Movement. This is the first book-length study of the protest movement that began in Toronto and became a global phenomenon. Observed annually on August 23—marking the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union—it commemorates the victims of Stalinism and Nazism.

Sołtys’s book is as much a study of an act of resistance, as a collection of primary sources and first-hand accounts and reflections. Although it devotes a number of chapters to an examination of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Treaty, its main strength and richness lay in the latter half of the book which focuses on the inception and evolution of Black Ribbon Day. It tells a story of how a small idea of an Estonian man in Toronto would resonate with millions of people in Canada and across the world.

In the mid 1980s, Markus Hess was in his early thirties—an energetic engineer with a passion for activism. Like many other members of his ethnic community, he objected to the Soviet occupation of his parents’ homeland. Equally abhorrent to him was the notion that any group resisting oppression had to resort to terrorism to be seen and heard. Refusing to accept that turning to violence was the only way to garner media attention, he decided that the same ends could be achieved by peaceful means. Two hurdles stood in his way. First, he needed to reach out beyond the small Estonian community in order to have larger impact. The other was finding a common denominator—a unifying message—that would ensure the cooperation of all the peoples from the Baltic and East Central European states.

In a recent gathering for the book launch organized at the University of Toronto, Hess emphasized the challenges of convincing the various peoples of Eastern Europe to cooperate given the complex historical legacies of the region. A meeting with Somerville led to the selection of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as a “date that had equal importance for all of our participating communities.” The distinct multicultural diversity of Toronto, where Estonians, Poles, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Latvians and others lived side by side, created a distinct opportunity that facilitated dialogue and understanding. Nonetheless, the complex Eastern European history was not easy to overcome. Hess opted for the policy of deferment—the struggle for freedom would trump all national geopolitical aspirations.

The book insightfully reveals how, in a short period of time, cooperation began to bear fruit. Representatives from various organizations found a common ground. The newly formed International Black Ribbon Day Committee (IBRDC) immediately went to work, creating a statement of purpose and launching an advertising campaign. Of all the television networks, only the CBC refused to play the commercials that depicted the German-Soviet collusion citing that such a collusion could not be historically verified. In plans for the first commemoration, the organizers reached out to their counterparts in the United States, Europe, and across the world.

The first Black Ribbon Day took place in the summer of 1986. In Toronto, the ceremony included the raising of flags of all oppressed nations under the Soviet yoke, followed by the carrying of a long coil of barbed wire to symbolize captivity. The message of peaceful resistance spread globally. Sołtys takes an encyclopedic approach to describing Black Ribbon Day events across the world. In Australia, for example, people gathered in Perth, Melbourne and Adelaide. Following speeches from community activists and parliamentarians, and the release of black balloons with names of victims, the Australian Black Ribbon Day Committee decided to initiate a mass boycott of artistic ensembles and imported goods from the USSR. Accounts of these commemorations pierced through the Iron Curtain to an audience that began to believe in peaceful protest.

By 1989, the seams of Kremlin’s power were reaching a breaking point. Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and other states were moving through a political revolution. The Baltic peoples refused to remain idle, even though the danger of opposing Moscow was much greater within the Soviet Union. Black Ribbon Day became a source of their inspiration. Nineteen-eighty-nine marked the 50th anniversary of the pact’s signing, which amplified its importance and the drive to resist occupation. The result was astonishing. Nearly a million Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians created a human chain that spread across nearly 700 km. This Chain of Freedom became the largest act of peaceful protest in history.

The Baltic Chain, the August 23, 1989 peaceful demonstration involving 2 million people joined in a chain stretching 419.7 miles across Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania

The legacy of the Black Ribbon Day was tremendous. We could talk of its immediate impact in Toronto and across the world, the media attention, the boycotts, or the fundraising successes. We could speak about the echoes across Eastern Europe, with the Baltic Way as a culmination of an idea. We could mention the post-independence conferences around transition to democracy which were organized by the IBRDM. We could discuss the official observance of August 23rd as the Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism in numerous countries, including Canada. Finally, we could list commemorations and monuments.

When asked about the legacy of the Black Ribbon Day Movement, Somerville wrote that “It is said that the price of liberty is eternal vigilance [and] the ability and the will to act in its defence.” If nothing else, he hoped that “Black Ribbon Day […] can keep alive the memories of the nightmarish partnership of tyrannies”. Unfortunately, as Aldous Huxley has aptly concluded: “That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons of history.” The comparison of Stalin and Hitler will remain elusive. And much of the work of the BDRM has been completely lost to almost all historical studies on the subject of the Revolutions of 1989 – 1991. Fortunately, Sołtys’s work offers a fascinating glimpse into the lives and work of the movement’s architects and supporters. It is an important contribution to anyone interested in explaining the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to Spring 2016!

Please see my book “The Whistler” by CM Gwizdak Greenwood at the moment only available on Amazon Kindle UK but shortly out in paperback. My factual family story covers the history of two million Polish citizens affected by Stalin’s terror, the Siberian deportations, Katyn, the loss of Eastern Borderlands and more…

What has been posted by you is absolutely true. Genocides are genocides. There is no dignity and privilege for communist crimes . Hitler and Stalin are equal in history.