|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What does the Polish folk dance movement in America have to do with Stalin? In the beginning there was… Igor Moiseyev (1906-2007) – a Soviet dancer and choreographer, Hero of Socialist Labor, recipient of three Orders of Lenin, the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, the Order of the October Revolution… He received three Stalin Prizes and was thrice named the People’s Artist of the USSR. In 1945-1946, he was awarded state medals by Bulgaria, Hungary, Mongolia, Poland, and Romania. His choreography for the ballet Spartacus of 1954 is still performed and so are his “folk” dances. In 1937, as a dancer at the Bolshoi Theater, he was asked to create a new art form, a “socialist-realist” antidote to the rotten bourgeois decadence of classical ballet and opera.

The Moiseyev Ballet State Academic Dance Company was established in February 1937, with a mission to create a hybrid art form in which folklore is magnified and transformed for the concert stage, small folk ensembles of musicians are replaced by a symphony orchestra, peasant voices by well-trained operatic style sopranos and tenors, and simple folk steps modified into complex stage routines. Stylized folk elements gave rise to sophisticated costumes, steps, and music arranged for symphony orchestra. Professional dancers and musicians performed suites of folk songs and dances organized by region, Soviet republic, or Soviet Bloc country. Moiseyev went on to create “character” dances that represented various sports, the Red Army, and the October Revolution. “Bulba” (“Potato”) became a Belorussian folk dance first on the stage, and then disseminated throughout the republic.

Perhaps there would have been nothing wrong with creating a new “folk art” to replace the old, even if done by political decree, if not for the context. Stalin decided it was time to supplant the traditional opera and ballet with folkloristic spectacles right before the Great Purge of 1937-1938, a period of intense repressions and mass murder. The celebrations of ethnic diversity in the Soviet Republics took place soon after the Ukrainian Holodomor (1932-1933), the planned and willfully orchestrated famine that killed between 2.5-7.5 million Ukrainians. The context also included repression of all “formalist” arts, including contemporary music and opera that affected, among others Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975). His opera Lady Macbeth of the Mstsensk District, premiered in 1934, was singled out for criticism after Stalin saw it in January 1936. Pravda denounced the work as formalist, “coarse, primitive and vulgar” and it was banned from the stage to be replaced by the uplifting productions of the Moiseyev Ballet Company.

In the meantime, Moiseyev’s premieres continued to coincide with important political events. In 1937, his company staged the Dances of the Peoples of the USSR, complete with Uzbek dances, while Uzbek leaders were arrested and “purged.” In 1941-42, during the Great Patriotic War following the German invasion, a spectacle was dedicated to Red Army recruits and partisans. The first great show of 1945, The Dances of Slavic Peoples, commemorated the conquest of Eastern Bloc countries. Interestingly for our study, this show included a Polish oberek and krakowiak, both transposed for the stage with added elements from ballet (spectacular leaps by men in the oberek and complex, large group figures in the krakowiak). In 1947, Moiseyev choreographed a new dance, “Pakhta,” (“Cotton”) with stylized movements imitating the motion of a tractor to celebrate the modernization of Central Asia (he also boasted of adding dance to cultures that did not know it). The march around the world continued in 1953, when the creation of North Korea and the end of the Korean War was marked with Peace and Friendship featuring dances from Korea, Mongolia, and China. The name of the style that the Moiseyev Ballet Company embodied to perfection was “socialist realism” – indeed it marked the creation of a new reality for the conquered peoples of Eastern Europe and Asia.

Let us now look at the establishment of the first, and most influential Polish group: State Folk Song and Dance Ensemble – Mazowsze. Created by a decree issued by the Ministry of Culture and Art on 8 November 1948, it was co-founded by composer Tadeusz Sygietyński (1896-1955) and his wife, cabaret actress and singer, Mira Zimińska-Sygietyńska (1901-1997). Their mandate was to create a folk group that would adhere to the principles of “socialist realism” and “express the spirit of the peasant core of the nation.” No expense was spared, no effort too large – the group received their own manor house in Karolin as a residence; elaborate replicas of folk costumes were ordered and hand-embroidered; auditions were held nationally and resulted in creating an ensemble of dancers and singers of astounding talent and beauty. The group’s first American tour, booked for 1961 by the well-known impresario, Sol Hurok, replaced the earlier planned performances of the ballet Harnasie by Karol Szymanowski, and built upon the success of the 1958 tour by the Moiseyev Ballet Company. Harnasie, a masterpiece of Poland’s 20th century repertoire, was based on the “górale” folklore of Podhale, the Foothills of the Tatra Mountains. Its rejection in favor of the stylized folklore of Mazowsze brought all regions of the Polish People’s Republic to the stage, with dance suites moving from the center of the country on the Mazovian plains, to the Tatra Mountains and to the Baltic Sea. With their spectacular costumes, acrobatic displays borrowed from Moiseyev’s choreography, and elements from classical ballet presented to sumptuous orchestral arrangements, the Mazowsze dancers conquered the hearts of American and Canadian Polonia.

Sygietyński, a well-known creator of Stalinist “mass songs” (My Beloved Country, The Six Year Plan…), composed new “folk-like” melodies to faux folk texts; over 50% of Mazowsze’s repertoire was composed, not arranged, by Sygietyński. Similarly, the choreographers – Zimińska-Sygietyńska and, later, Witold Zapała (b.1935, with Mazowsze 1957-2011) “improved” upon the actual dance steps – the men performed high leaps, the couples separated for elaborate “star” and “windmill” figures rotating around the whole stage. In the oberek, women supported their partners who leaped high into the air just as they did in the Moiseyev’s Ballet’s “oberek” – and this image graced some of Mazowsze’s promotional posters. Then, there were “historical-themed” suites depicting King John Sobieski and his wife Marysienka, or the 1815 Warsaw Duchy army with their consorts in high-waist Empire dresses. In short, “authentic” it was not… But popular? Of course! In 1961, Mazowsze performed 72 concerts in the U.S. and 5 in Canada; in 1964 – 67 and 14 respectively; returning in 1971, 1873, 1976, 1982, 1985, 1989, 1992, and 1997.

Formed in 1953, with an even stronger ideological mandate than Mazowsze – to prove that Silesia has always been fully Polish – the Śląsk State Song and Dance Ensemble actually preceded Mazowsze’s appearances in America. Soon, the group was described by Zimińska-Sygietyńska as a “dangerous competitor” of her Mazowsze. Śląsk’s first tour of 1959 was promoted under the banner of “authenticity” – the founder Stanisław Hadyna (1919-1999) had apparently toured distant villages to find dancers “unspoiled by the stage routine” and hired 100 youngsters from a pool of 12,000 applicants including “goose girls in villages and mountain shepherds.” The dance suites of Śląsk were organized by region, and portrayed regional customs and costumes, with an emphasis on Silesian traditions. Śląsk’s first choreographer, Elwira Kaminska (1912-1983), a student of Russian star Jurry Peregrin, brought Soviet-style acrobatic virtuosity to her ensemble. The group’s popularity was a given: its website boasts 6000 shows worldwide, with an audience of 20 million.

What was the effect of the State Folk Song and Dance Ensembles on folklore in Poland? As musicologist Jan Stęszewski claimed in 1995, they ruined the eyes and ears of the audiences with their symphonic sounds and elaborate stage routines. Authentic folklore became “boring” in comparison with these Broadway-style revues. Luckily, enough scholars were concerned and counter measures were taken, leaving the stylized folklore on the stage, but teaching more authentic folklore to students and children, in Poland and abroad.

What was the effect of the State Ensembles on American audiences? The spectacular success of Mazowsze and Śląsk in North America had less to do with the “authenticity” of the spectacles they presented, and more to do with the cultural needs of the immigrant populations. Starkly anti-communist, American Polonia embraced a key export of the Polish People’s Republic, an ideological product manufactured to reproduce the main traits of a Soviet model and help assert Soviet dominance in Poland. Why? Perhaps to relieve the pain of Polish jokes, the poverty and depression among the displaced persons who lost everything, including their language and home… The new arrivals to America turned to folk dancing to assert their lost identity; they made folk costumes from memory, imitating the traditions they wanted to bring back to life and pass on to their children. The dance groups formed as social clubs for adults and at schools for children – to keep children Polish, to help them remain in touch with the Old Country traditions. And, enthused by the professional quality of spectacles such as Mazowsze that made them “proud to be Polish,” Polonia activists set out to learn from the State Ensembles and steal their dancers. Let me show you a couple of examples.

Since its foundation in 1956 by a small group of WWII veterans and orphans, the Polish Folk Dance Ensemble Krakusy of Los Angeles served the twin purpose of asserting Polish identity and perpetuating it among children. The group’s transformation by dancers who defected from Śląsk, Staszek Danko (1966) and Marylka Klimek George (1967), resulted in its rise to prominence and high-profile appearances at Polish celebrations, as well as city-and-state-wide festivals and events. Klimek George, the artistic director and choreographer, borrowed stylized music and complex choreographies from the repertoire of Śląsk, with its acrobatic figures, high leaps, separation of dancers, etc. It needs to be said, though, that the Krakusy of today has evolved far beyond the heritage of stylized folklore. The dancers learn more “authentic” dance routines and songs from its Polish-trained professional folk choreographer Edward Hoffman. Under his leadership, the group received specially commissioned recordings from Poland and learned new steps more faithfully portraying real folk customs.

The founder of “Polskie Iskry” (established in 1967 as Orange County Folk Dance Workshop), Eugene Ciejka (1930-2007), a ballet dancer from New Jersey, had been a member of the East-coast Polish American Folk Dance Company, but studied Polish folk dancing with Śląsk during workshops in Poland in 1972 and 1977. Like Krakusy, his group used Śląsk music and choreography in some numbers. Ciejka also created his own “folk-style” choreography for his group of dance enthusiasts, not all of them Polish (this feature and the presence of African-Americans and other non-Polish dancers distinguished Polskie Iskry from other ensembles).

Morley Leyton, a professor of dance at Temple University who had started dance studies in 1955 with Jarek Lazowski of the Polish Dance Theater of New York, spent the year 1970 learning folk dance from Mazowsze in Poland. With Monique Legare, a Quebecoise ballet dancer who studied folk dancing in Bulgaria and Hungary, Leyton founded Janosik Dancers in 1971 in Philadelphia. The group’s website leaves no doubt about its heritage: “Janosik has had special workshops with the Polish State Folk Dance and Song Ensemble, Mazowsze, whenever they visited Philadelphia. There has also been a workshop with members of Śląsk, another well-known company of Poland.”

The year 1975 saw the birth of Łowiczanie Polish Folkdance Ensemble in San Francisco. Founded by Krystyna Chciuk with her three daughters, it was soon transformed by the choreography of Jan Sejda, the ensemble’s artistic director and choreographer from 1978 to 1982. Sejda, a former dancer of Mazowsze, brought the stylized stage repertoire and national/regional suites of dances of his parent company to San Francisco. Łowiczanie often traveled to Poland for folk dance festivals and was one of the co-founders of the Polish Folk Dance Association of the Americas.

In 1991-2008, Krakusy had a Los Angeles competitor in the form of the Polish Folk Dance Company Podhale, founded by John (Jasiu) Sobański, a former member of Krakusy, who had studied with Mazowsze (under Witold Zapała) and was admitted to the Polish group for a brief period in the 1990s. Sobański’s least “authentic” brand of folklore used Mazowsze music and choreography and was criticized in Poland for its lack of originality, though praised in California for the energy, talents, and dedication of its dancers.

The proliferating dance groups united in the Polish Folk Dance Association of the Americas. Established in 1983 by six ensembles, the association currently has 33 members. Fourteen groups are named after Poland and all things Polish; six after Kraków or its inhabitants; four after the region of the Tatra Mountains; and four after Mazowsze. The Silesian experiment did not work out… but Polish folk dancing is alive and well in immigrant communities of North America. Folk dance groups are associated with PNA (Polish National Alliance) lodges, PWA (Polish Women’s Alliance), PRCUA (Polish Roman Catholic Union of America), and Polish clubs or schools. They are managed by volunteer boards, and funded by contributions from organizations and individual dues. They provide a way to socialize Polonia children and teach Polish history and culture. They also serve to affirm ethnic identity and difference in public performances at community events and in an “international” ethnic context. As such, these ensembles respond to a deeper need that was expressed in social clubs and dance groups long before Mazowsze and Śląsk took America by storm. Does it matter then, that so much of this activity has taken place under the ghost of Stalin? CR

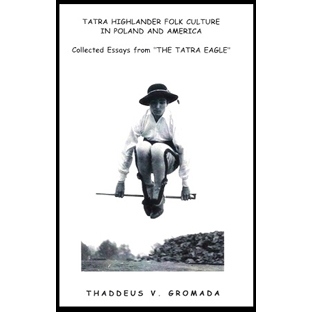

This article is based on research by Maja Trochimczyk, published Polish Dance in Southern California (Columbia University Press, East European Monographs, 2007), and presented in “The Impact of Mazowsze and Śląsk on Polish Folk Dancing in California” (Polish American Studies 63 no. 1, Spring 2006, pp. 1-34).

Imagery

- Oberek

- Krakowiak

- Mazur

- Kujawiak

- Polonez

- Zbójnicki

- Polka

- Mazowsze, 1964 cover

- Kujawy folk costumes, by Oskar Kolberg, 1867

- Oberek folk costumes, Mazowsze region, 1885

All imagery courtesy of Maja Trochimczyk

…you seen to have forgotten E. Palpinski…choreographer for the early Mazowsze…it is his Kujawiak…

Actually, Polonia’s first folk dance groups originated before World War II, during the 1930s and others were formed before Mazowsze ever sent foot in America. New York’s was formed in 1938, Minnesota’s in 1949. But there were earlier examples from the mid 1930s. No doubt Mazowsze encouraged more of it, but the idea did not originate with Stalin.

There is some evidence that the first folk dance groups originated in urban settlement houses as Anglo reformers sought to find ways for diverse ethnic groups to express themselves in an American context.

Also the first seven folk costume images used for the article are examples of Art Deco illustration from the 1920s or 30s. I believe the originals are in National Museum in Krakow.

Stalin, of course, didn’t invent folk dancing as an art form, and parents have always loved dressing up their children in folk costumes (and who doesn’t like dress-up, including grownups?). Stalin used folk dancing as a propaganda tool to: 1) make it look like the Bolshies loved ethnic communities; and 2) to take all attention away from “higher” culture because his minions did everything possible to suppress it or denigrate it.

Polish dance is indeed alive and well in America. I have observed,however, that most members seem to quit dancing when they reach their late twenties.One exception is janosik, in Philadelphia,whose members have gray hairs, but continue to enjoy performing.

Pingback: Maja Trochimczyk | Laatuasunnot

Pingback: Maja Trochimczyk Facebook | Laatuasunnot

Pingback: Welcome to Winter 2016!