Polish Orphans of Tengeru: The Dramatic Story of Their Long Journey to Canada 1941-49

Polish Orphans of Tengeru: The Dramatic Story of Their Long Journey to Canada 1941-49

By Lynne Taylor

Dunburn Press, 2009, 278 pp.

ISBN: 978-1554880041

Lynne Taylor, a professor of history at the University of Waterloo, published her marvelous book, Polish Orphans of Tengeru: The Dramatic Story of Their Long Journey to Canada 1941-49, in 2009. Almost immediately, the book was translated and published in Poland. Not surprising. It’s a great story, well told.

In an interview in one of Poland’s most important newspapers, Rzeczpospolita, (May 11, 2010) Taylor was asked if she had encountered any objections from other historians. An odd question, one would think. But Professor Taylor didn’t ask for a clarification; she replied that times have changed and the influence of radical leftists in western universities is no longer so strong.

That change was slow in coming. I recall a professor in the early 1980s ridiculing my statement that the Soviets had deported Polish citizens during their occupation of eastern Poland; that my family was among those deported impressed him not a bit. Nor would he agree that the Soviets had signed an agreement to attack Poland in concert with Nazi Germany, partition the country, and cooperate in suppressing all resistance. A Marxist, he followed the official Soviet Party line.

However, in the past couple of decades the number of books documenting the Soviet role in World War II has been increasing each year. Lynn Taylor’s book is a welcome addition.

Polish Orphans of Tengeru focuses on the story of 123 children who were brought to Canada in 1949 at the end of an epic journey that began with the mass deportations of Poles in 1940 to the slave labour camps of the Soviet Gulag in the Arctic, Siberia and Kazakhstan. Then, in June 1941, the Nazi dictator turned against the Soviet one. Stalin was suddenly in need of help.

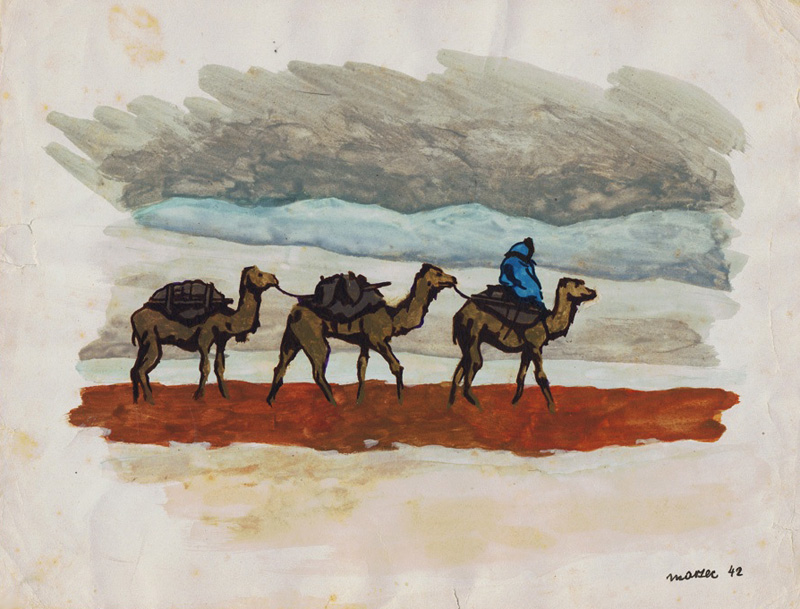

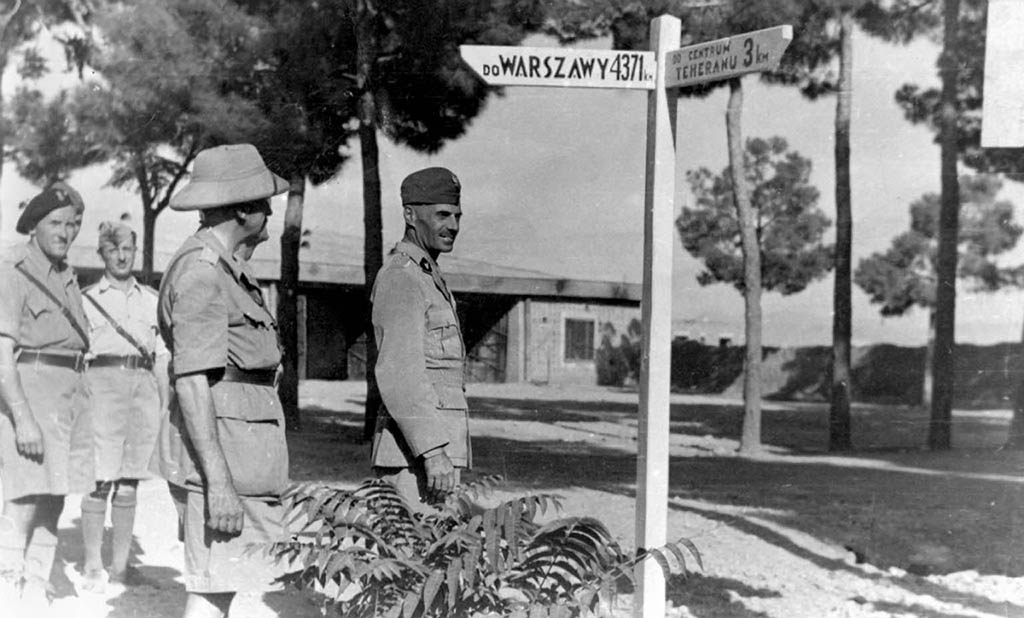

As a condition of a new alliance with the West, Stalin agreed to release his Polish prisoners, and to allow the formation of a Polish army under the command of General Władysław Anders, who had been held in the infamous Lubyanka Prison. By that time, many prisoners had died and the survivors had little chance of getting out of the country, but Anders succeeded in getting his army evacuated to the Middle East, and to take some 50 thousand civilians out with him, including thousands of orphaned children, with him.

And so began the next phase of this dramatic odyssey as the women and children were sent to various refugee settlements in India and Africa to await the liberation of Poland. There was no liberation; at war’s end Poland’s allies acquiesced to Stalin’s demands to annex almost half the country and to impose Soviet rule on the rest. The refugees were stranded.

Repatriation was an option that almost all of Stalin’s former prisoners understandably rejected. Finding countries to accept them was not easy, and it was not until 1949 that the last of the orphaned children were accepted by Canada. And then, the Soviets were back in the picture again. Protesting to the United Nations that the children were kidnapped, and that their true home was in Poland – as though they had not torn them from their homes in the first place. They demanded their “repatriation,” making no mention that they had actually annexed the part of Poland where these children’s homes had been. Taylor does not miss the irony.

Taylor’s telling of the human tragedy and the political maneuvering is first rate, not least because she was obviously also quite taken by the other aspect of the children’s story, their great adventure. Having lived in Tengeru myself, I am familiar with the exotic and joyful side of this story.

The children did swing on vines like Tarzan, they did skip school because they could not resist the lure of the jungle, they did live in a place of indescribable natural beauty. In primitive huts, with precious few material possessions and yet, I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard: “We were never bored.” Imagination and ingenuity, friendship and adventure, and a lot of freedom. Today’s kids should be so lucky. I have heard over and over again that Africa itself had a lot to do with their recovery from the trauma of Siberia.

If there is one shortcoming – and I use this word reluctantly because this really is a terrific book – it is that Taylor’s archival sources did not include the Sikorski Institute in London. The Canadian archives and UNRRA are essential, but the Polish sources would have rounded out the story.

Not many refugees have reunions. Refugee camps are depressing places of despair. The refugees of Tengeru (and those from the other settlements (not camps, whether in Africa and India) have frequent, regular and joyful reunions. To be sure, they remember their losses, the fear, and the hunger, but they don’t want to forget Africa.

The schools, sports, music and theatre, the hikes and scout camps, the trips to the source of the Nile or the foothills of Kilimanjaro, all this did not just happen; somebody made it possible. Since most of the people who remember these settlements were children then, they didn’t give much thought to this, no more than any children give much thought to their parent’s budget and other responsibilities.

The schools were set up by the Government-in-exile, (not by priests and nuns of whom there weren’t many). There was a lack of supplies, and not enough teachers, but all of these children eventually went to other countries and managed quite well, despite having to do so in a new language. What was missing in “supplies” was made up for in dedication.

The entertaining stories about skipping school are all true; I scarcely know anyone who could resist. However, this neither surprised nor shocked anyone in authority. Minutes of meetings attended by Polish and British officials bring up the issue of discipline: the British insisted the Poles were too lax and that more severe punishment must be used; the Poles replied that corporal punishment of children was against Polish law. They also pointed out that after Siberia, the use of force was unimaginable.

Orphans had their special sorrows: nobody can replace a mother. But, as Taylor rightly points out, they were treated with special deference. My mother was a teacher and also worked in the school office. She often told me, “If you love only your own children, you don’t love children at all.” And my older sister recently recalled that other kids were sometimes resentful: “Orphans, orphans. We were always being told the orphans were special,” And indeed, that sentiment is often expressed in the Polish records.

Among other subjects discussed with the British were unpaid work, salaries, savings, and various other issues. Everyone in the settlement – and perhaps here I should explain the term: The British wanted camps; the Poles insisted they were not prisoners but civilian refugees of an allied country, and they were living in temporary settlements, not camps. Nor would the Polish authorities permit coerced labour: everyone contributed voluntary work but nobody could be forced to do full time unpaid work. The same with forced savings. They rightly pointed out that life in the settlements was hardly a life of luxury, and dressing oneself and one’s children decently was hardly decadent. And they definitely refused to pay “duty” on clothing sent to them by Polish Americans. On the other hand, the farm established by the community was so successful that it later was taken over by Tanzania’s Ministry of Agriculture & Food.

Self-sufficient and self-confident refugees do not necessarily endear themselves to officials. To some, the Poles had unrealistic expectations: keeping what’s left of their families together, educating their children, providing them with cultural activities in the heart of a jungle.

After 1945, when the British withdrew recognition from the Government-in-Exile, conditions deteriorated. Nevertheless, many teachers and guardians remained on the job and did their best with less. Those earlier years, however, when the refugees had protection from their government, were the years when their hope, dignity and strength were restored. That prepared them for the challenges to come.

The children who came to Montreal had a pretty tough time, mostly because, as Taylor points out, their family, or “tribe,” was broken up. Great care had always been taken to keep orphans together, not only siblings but also friends who had become surrogate family.

Orphans were made to feel important, equal to all others. Taylor writes of a Canadian official’s concern that these orphans may actually have been “illegitimate,” and therefore of “poor stock.” I spoke to one woman in Montreal who told me they overheard these comments. It was a shock, an utter humiliation. Not once, she said, had they ever heard such a thing in Africa.

It must be stated that for all the policies and rules put in place by Polish authorities, there must have been individuals who were unkind, at least some of the time. It was not paradise; but as refugee settlements go, they were peerless.

Officials had a job to do and that job included rules and budgets; a job well done was one that solved a problem as quickly and efficiently as possible. Some officials were petty and harsh, some not; some were prejudiced – I personally don’t remember any “primitive illiterates” among us but one Canadian official dismissed all the refugees as such – but others were understanding and respectful.

Taylor is to be commended for writing a book that so beautifully tells a story of ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, their resilience, their courage and their strength. The history is well researched, and beautifully presented with a personal touch. It’s a book that should interest anyone, not only those with a connection to the story.

CR

Irene Tomaszewski- I read your article about Camp Tengeru and it is GREAT

I lived there as a child from 1942- 1950 now live in Chicago Area.

My Nephiev Greg Archer wrote a book about me and my family- Siberia Tengeru

and more. The name of the book on Amazon is GRACE REVILED/ by Greg Archer

Hope you can contact Greg

Regards- John Migut

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption